Contents

Guide

A Little Trouble with the Facts

The Anatomy Lesson

Youll Thank Me for This

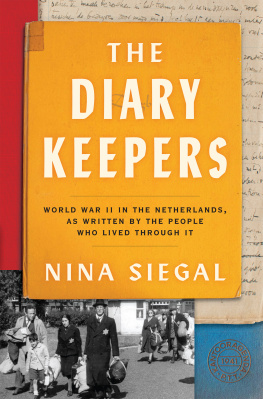

For the photos on these pages, grateful acknowledgment is made to the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam; the Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsarchief (Amsterdam City Archives); the Vrijheids Museum (Freedom Museum) in Groesbeek; the Joods Museum (Jewish Museum) in Amsterdam; and the author, Nina Siegal.

Cover: Photo by Herman Heukels, a Dutch propaganda photographer and NSB member who shot a series of images of the large Razzia in Olympiaplein on June 20, 1943. None of the individuals in the photograph have been identified. Heukels took the pictures in hopes of publishing them in Storm SS, a Dutch Nazi propaganda weekly, but they never appeared there. His pictures are some of the only official shots of the round-up of 5,500 Jews in Amsterdam that day. (Courtesy NIOD)

THE DIARY KEEPERS . Copyright 2023 by Nina Siegal. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ecco and HarperCollins are trademarks of HarperCollins Publishers.

FIRST EDITION

Cover design by Allison Saltzman

Cover photograph: Jewish families at the sports complex on Olympiaplein in Amsterdam, awaiting deporation to Westerbork transit camp on June 20, 1943; photograph by Herman Heukels NIOD, CCO

Diary covers and pages from the NIOD archive, Amsterdam; photographs Ilvy Njiokiktjien / VII / Redux

Title page background LiliGraphie/shutterstock.com

Digital Edition FEBRUARY 2023 ISBN: 978-0-06-307067-7

Version 01252023

Print ISBN: 978-0-06-307065-3

This book is dedicated to my grandfather, Emerich, my grandmother, Alzbeta, my mother, Marta, and all the Safar and Roth family members we lost in the war.

And it is also dedicated to the next generation of our family, my nephews, Joseph and Cameron, and my daughter, Sonia.

Everyone wrote. Journalists and writers, of course, but also teachers, public men, young peopleeven children. Most of them kept diaries where the tragic events of the day were reflected through the prism of personal experience. A tremendous amount was written, but the vast majority of the writings was destroyed.

Emanuel Ringelblum, creator of the Oyneg Shabes underground archive in the Warsaw Ghetto

Nobody will ever tell the storya story of five million personal tragedies every one of which would fill a volume.

Richard Lichtheim, from the Jewish Agency in Geneva, July 9, 1942

Contents

Radio Oranje reporters, including Loe de Jong (center), gathering around the microphone

Courtesy NIOD photo archive

O n March 28, 1944, the crackling voice of Gerrit Bolkestein, Dutch minister of education, arts and sciences, came across the airwaves from London on Radio Oranje, the broadcast station for the government in exile. Ten months earlier, everyone but Dutch National Socialists and other German sympathizers had been forced to turn in their radio sets, under threat of punishment. But lots of people kept a hidden device, and on this occasion, those who had them huddled around their illegal transmitters in closets or attics or by the back door of the barn to listen:

History cannot be written on the basis of official decisions and documents alone, Bolkestein told his listeners, whod spent nearly four years living under German occupying forces. If our descendants are to understand fully what we as a nation have had to endure and overcome during these years, then what we really need are ordinary documentsa diary, letters.

He urged Dutch citizens to preserve their personal journals and other intimate correspondence that conveyed their private struggles and personal wartime ordealsmaterials that the Nazi overlord did not even want them to have. Not until we succeed in bringing together vast quantities of this simple, everyday material will the picture of our struggle for freedom be painted in its full depth and glory.

Bolkestein and other Dutch officials had fled the Netherlands after the German invasion in May 1940 and had been operating in exile. It had been a painful four years, as theyd seen their country overtaken by fascist ideology and hundreds of thousands of their citizens drafted into service for the Nazis, deported to work camps and concentration camps.

By the spring of 1944, the end was in sight. At the very least, there was reason for hope. The war had reached a turning point at Stalingrad, the Allies were making clear advances, and the German army was finally in retreat. Even in pro-German circles, the general expectation was that an Allied invasion of Western Europe was only a matter of time.

On Radio Oranje, Bolkestein let the people know that the stories of individual struggles, personal experiences, written in ordinary peoples own words, would be valued by future historians. He promised those listening that the government would establish a new national center for war documentation, and that it would collect, preserve, and publish this material, which would illustrate the character and stamina, the courage and endurance, of all of his countrymen and women.

A young raven-haired Jewish girl named Anne Frank, an aspiring teenage writer, was listening. She tuned in from her hiding place in an attic on the Prinsengracht, where shed lived in fear for nearly two years, while the vast majority of her friends, schoolmates, and their families had been dragged away.

Anne had been writing in her diary since her thirteenth birthday, when she received it as a gift, and addressed it as Kitty. That was just weeks before she, her father, Otto, her mother, Esther, and her older sister, Margot, had moved into the attic, which they would end up sharing with four near strangers.

Mr. Bolkestein, the Cabinet Minister, speaking on the Dutch broadcast from London said that after the war a collection would be made of diaries and letters dealing with the war, she scribbled in her journal the next day. Of course, everyone pounced on my diary.... Ten years after the war people would find it very amusing to read how we lived, what we ate and what we talked about as Jews in hiding.

The young diarist immediately set aside Kitty to begin a new, revised version she planned to call The Secret Annex, which she hoped to publish as a novel. The title alone would make people think it was a detective story.

Anne Frank was among thousands of Dutch civilians tuning into Radio Oranje that night who dared to hope that the war would be over soon enough for them to publish their reminiscences. Some picked up their pens and started to jot down notes, inspired by Bolkesteins suggestion. Thousands of others had been recording daily wartime experiences since the first day of the German invasion. Many people started these diaries from the tenth of May 1940, saying that they never had a diary before, said Kok.

WE TEND TO think of history as a story that is written at some temporal remove from the events described. Was it unusual that Netherlands Minister had already obtained approval from the Dutch Cabinet to found an institute focused on a war that hadnt even ended? It would be another half a year before the Allies won any significant battles in the Netherlands, and fourteen months before the entire country would be liberated.