Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

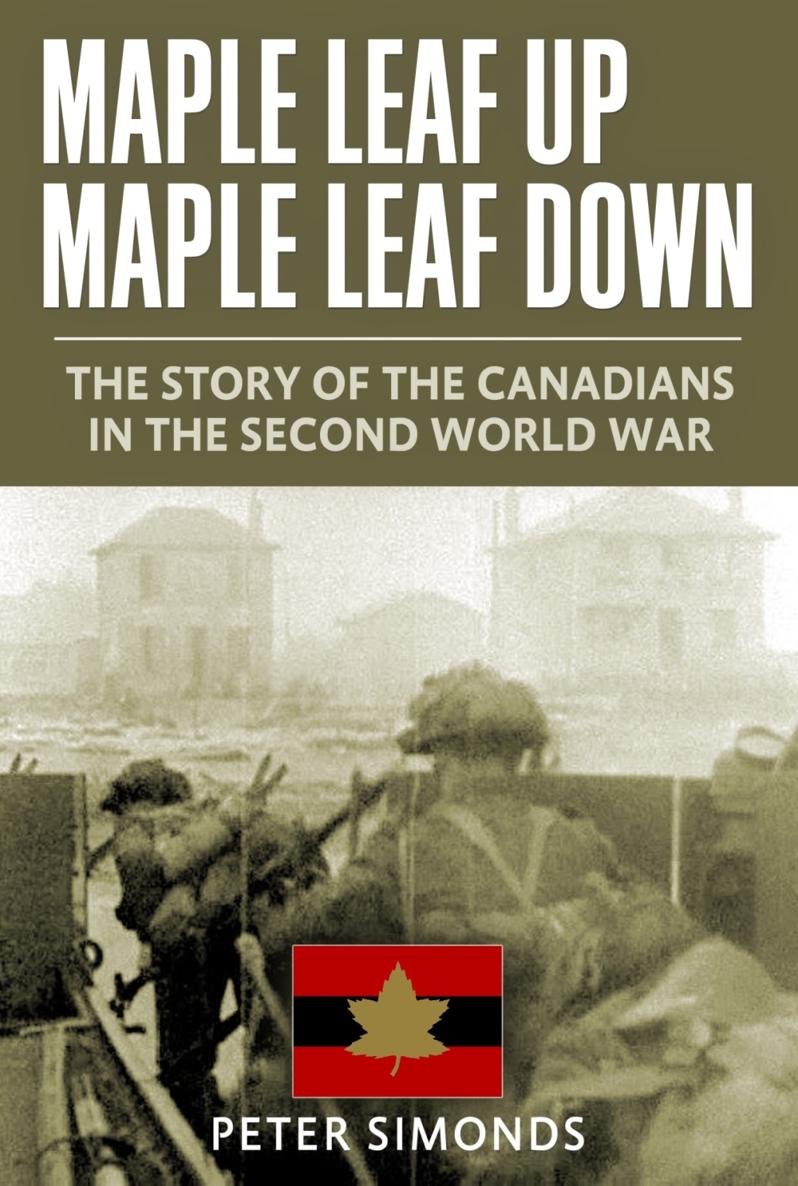

Maple Leaf Up, Maple Leaf Down

The Story of the Canadians in the Second World War

By

PETER SIMONDS

Maple Leaf Up, Maple Leaf Down was originally published in 1946 by Island Press Cooperative, Inc., New York. Cover image: Canadian Army troops landing on Juno Beach, June 6, 1944.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

There were eight Allied armies engaged against Germany on the Western Front of the Second World War. Reading from north to south, as they operated along the front, they were: The First Canadian, Second British, American 9 th , 1 st , 3 rd and 7 th , and the French First. The American Fifteenth army arrived on the scene during the later stages of the war and operated in the zone of the 1 st and 9 th U.S. Armies.

This narrative is mainly about the first named of these formations, the First Canadian Army, although it necessarily touches on the war as a whole, particularly the operations of Field Marshal Montgomerys 21 st Army Group. In the latter respect, I hope it serves to answer some of the criticisms leveled at the British commander and his operation of the army group composed of First Canadian and Second British Armies.

The book is also an attempt to describe Canadas war effort on the ground as a whole, from the arrival of the lone Canadian division in England under General McNaughton in December, 1939, through the Dieppe raid, Sicilian and Italian campaigns to V-E Day.

The title, perhaps, requires a brief explanation. Maple Leaf Up was the name of the main route to First Canadian Army during the whole Western Europe operation. To get to First Canadian Army, one followed the painted maple leaf or written words, MAPLE LEAF, plus the word UP; to get back to the rear areas, away from the army, one followed the maple leaf signs, plus the word DOWN. The tanks and vehicles loaded with supplies and reinforcements for the army rolled along MAPLE LEAF UP; the empty trucks and full ambulances rolled along MAPLE LEAF DOWN.

I was going to call this book MAPLE LEAF UP at first, because this title suggests the shining record of Canadian arms, and the robust good nature and optimism of Canadas sons who fought with such distinction in the Second World War. Then I thought of the thousands who lay buried on European soil and of the heart-breaking set-backs as well as victories the army had absorbed in its long march to victory with its Allies. MAPLE LEAF UPMAPLE LEAF DOWN suggests both sides of the story, which I also struggle to convey in the following pages.

PETER SIMONDS

Edmonton, May, 1946

CHAPTER ONE Background to Battle

Captured documents and verbal statements by members of the Nazi High Command suggest that the German military hierarchy of World War II regarded four Allied field commanders with considerable fear and respect. They were Field Marshal Montgomery, Generals Omar Bradley and George S. Patton, and Marshal Zhukov. These documents are substantiated circumstantially by the deployment of their units of S.S. men to bolster the ordinary German soldier on sectors commanded by these four generals. In the fateful and history laden summer of 1944, the Germans had eight percent S.S. men stiffening their forces opposing Marshal Zhukov (high for the Eastern Front); about fifteen percent on the American 12 th Army Group sector of Normandy; twelve percent opposing General Dempseys Second British Army (under Montgomerys 21 st Army Group) in Normandy; and fifty-five percent facing General Crerars First Canadian Army of 21 st Army Group at the Caen hinge.

There seems to have been two main reasons for the Germans high concentration of S.S. troops opposing the Canadians in Normandy; the importance of the Caen hinge position to their whole Normandy front; and their high estimate of the fighting qualities of the individual Canadian soldier.

Marshal Foch on witnessing a fast and rough game of ice hockey between Canadian teams not long after World War I, was heard to exclaim: Mon Dieu, if thats the way Canadians play, no wonder they can fight! By his ruggedness and individual initiative the Canadian soldier has been a source of major worry and sorrow to the German in both World Wars.

Johnny Canuck was a volunteer soldier (with the exception of a few thousand Zombies brought in towards the dying stages of the war as reinforcements; Zombies were National Resources Mobilization Act men who originally were conscripted on the understanding that they would be used for the home defence of Canada only). As a result, he did not truly represent a cross-section of his country like the average G.I. or Tommy. He was not a conscript; he wanted to fight. Relative to other Allied soldiers, he was comparable to a German S.S. man on the enemy side. He was a shock trooper. While the British Tommy left home amid warm handshakes and the understanding farewells of his friends, because his country was fighting for its very existence; and the American G.I. left home to the tune of brass band, tears and fond farewells, because he, too, must go; the Canadian soldier often left with a strange psychological veil between himself and his relatives. Canada was not directly threatened; he didnt have to go.

If married, his wife often wanted him to explain why he volunteered to go and get shot at, without National Conscription compelling him to do so, if he really loved her and the children. Often he ended up buried on a lonely hill or alongside a road in Normandy, Belgium, Holland, Italy or Germany, with a small Maple Leaf whose color designated his formation, on the white cross bearing his name. Some French, Belgian or Dutch child might place a posy of wildflowers on the grave in memory of the lean, tough Canadish or Les Canadiens they had watched go through their village or past their farm with awe.

While it is probably true that the First Canadian Army contained more genuine idealists than most Armies of World War II, it is also true that it held its share of toughseven a few criminalsand ambitious egoists whose careers always came first and to whom the war was merely an elaborate stage setting and backdrop to furthering their own interests. To this class, Army politics were the breath of life. Some of them climbed to high places in the early confused months of the war and remained as expensive luxuries, but others, fortunately, were dropped by the wayside when the Canadian Army finally got down to business.

No one can write a discerning picture of the Canadian Army Overseas without considering the complicated politics which were a part of its life from birth and which, at times, threatened to suffocate it as an efficient fighting force. The politics did not emanate from interference by members of the Canadian Government, but from the nature of the Canadian peace-time army.