THE TRAGEDY OF THE ASSYRIAN MINORITY IN IRAQ

This is a fascinating account, by a British Army officer in Iraq, of a little-known ethnic minority in that country. The Assyrians, like other minorities in the area, lived across many modern national boundaries. Unlike other ethnic groups, they were distinct and usually well-off. The land became Christianized, and after the end of the British mandate in Iraq in 1932, it was revealed that the Assyrians were being persecuted by the Moslems. The survivors of the Assyrians, a once-great people and a once-great Christian Church, lived in the Hakkari mountains in the northeastern part of Iraq.

THE TRAGEDY OF THE ASSYRIAN MINORITY IN IRAQ

R.S. Stafford

TRAGEDY ASSYRIAN MINORITY IRAQ

First published in 1935 as The tragedy of the Assyrians George Allen & Unwin Kegan Paul Limited

This edition first published in 2009 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2004

Transferred to Digital Printing 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-0893-0 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0893-1 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

TO

MY WIFE,

WHO REMAINED IN MOSUL

DURING AUGUST

1933

History, which is indeed little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind.Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,

PREFACE

IN August and September 1933 reports of events which had been taking place in northern Iraq occupied some space in the columns of the daily press, not only of Great Britain, but of Europe. For some years previously comparatively little attention had been paid by the British press to the affairs of Iraq. The termination of the British mandate in October 1932 and the consequent complete independence of Iraq had been welcomed in England with much satisfaction; indeed, practically the whole British press had long advocated the curtailment of British responsibilities and expenditure in that country. Sincere good wishes for the success of the new Iraqi state were universally expressed. In the summer of 1933, King Feisal, to whom more than to anyone else Iraq owed the fulfilment of her national aspirations, paid a state visit to England, where his charm of manner and attractive personality made a deep impression on all who met him. As a result of this visit hopes for the continuance of close and friendly relations between the two countries were strengthened.

Up to the summer of 1933 comparatively few people in England were aware of the existence of the Assyrians in Iraq. Ecclesiastical circles had, indeed, been interested in this Christian remnant, and there were others who had expressed concern regarding this minority in the north of Moslem Iraq. The reports of the massacres of Christians by Moslems came as a shock to everyone, and not least to those who had at heart the future of Iraq. These reports alleged that large numbers of Assyrians had been murdered. None of the accounts given were accurate, either as to the details of the massacres or as to the causes which had brought them about. In Iraq a veil of secrecy was successfully imposed, and the news that trickled through became more and more scanty, and more and more inaccurate. On September 5, 1933, King Feisal died very suddenly in Switzerland, and this sad event, though it once more brought Iraq temporarily into the news, rather helped to submerge the Assyrian question. Since then, so many more important events have occurred throughout the world that very occasional references to it have appeared in the press, and the question has been forgotten by all but the small section of people who are really interested.

Even these people, however, are by no means fully informed of what actually happened. The inevitable result, in the absence of any authoritative statement, has been the circulationoften by means of pamphletsof all manner of garbled accounts. These accounts have been equally unfair to Great Britain, to Iraq, and to the Assyrians. It appears only right that a true account should be given of what really happened, and why it happened. This is the object of this book. A no less important object is to show that the future of the Assyrians is still unsettled. Something must be done for this unfortunate people. They have suffered much, and if some of their sufferings have been the result of their own folly, allowance should be made for the circumstances in which they found themselves. People who feel they are unwanted are not likely to make easy or pleasant guests.

My duties as Administrative Inspector in Iraq, where I had been for six years, brought me to Mosul in May 1933. I was thus in the closest touch with the Assyrian situation as it developed that summer, and I was in a unique position to know what really took place. I have endeavoured to write as impartial an account as possible. If I have been compelled on occasions to criticize the conduct of the Assyrians, I hope that it will be realized that I am far from lacking in sympathy towards them. If I have written strongly of the behaviour of a section of the Iraqi army, let it not be thought that I have done so in any spirit of ill will towards Iraq. On the contrary, than myself there is no more sincere well-wisher of that country, and this, I venture to hope, will be understood by my many Iraqi friends.

CONTENTS

THE TRAGEDY OF THE ASSYRIANS

CHAPTER I

EARLY HISTORY

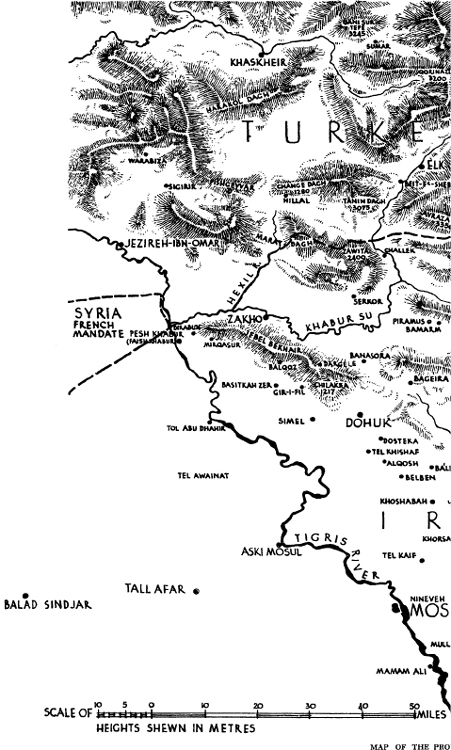

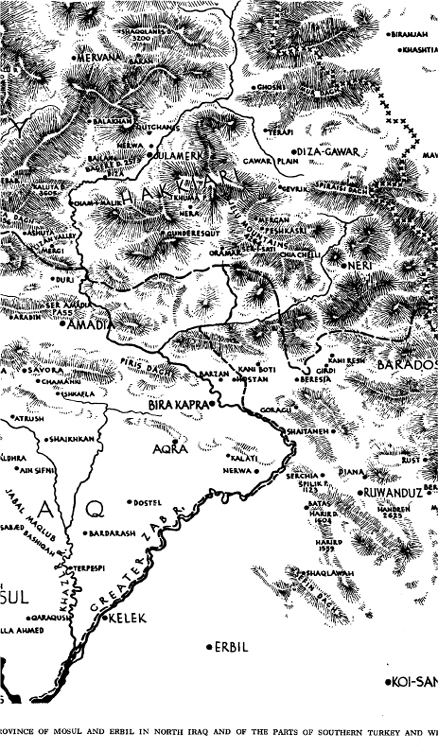

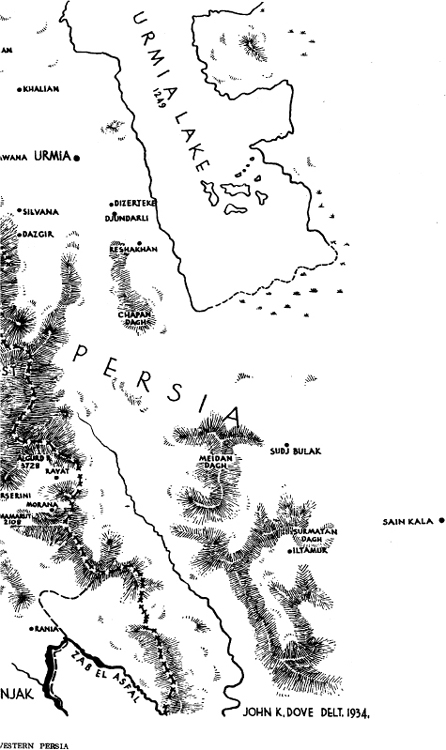

JUST north-east of the present-day boundary of Iraq and within the borders of Turkey there is situated a tangled mass of mountains, generally known as Hakkiari. These mountains resemble those of Switzerland, but the country is on an even grander scale. The valleys are narrower; many of them, indeed, are precipitous gorges falling thousands of feet from the high mountains above and bearing little vegetation except a strip of green along the torrent at the base. The mountains rise to 12,000 and even to 14,000 feet. In summer snow lies on the highest peaks and in winter even in the lowest valleys the snow is deep. The scenery is magnificent, particularly where the Greater Zab river bursts its way through the mountain mass in a series of deep and narrow gorges with falls and rapids as the river drops. Great forests of oak, juniper, and, more rarely, pine and maple cover the mountain-sides. In the valleys there is a profusion of rhododendrons, arbutus, hawthorn, and other small trees and shrubs. During the short spring, which follows the melting of the snows, the ground is carpeted with every kind of Alpine flower. The fauna is of the usual Caucasian typewolves, bears, hyenas, ibex, martens, and foxes. The bird life ranges from tiny pipits and larks to the eagles and vultures that inhabit the higher crags. Chikor abound to attract the sportsman, and there is excellent fishing to be had. This land, where only a virile people could hope to survive, has seldom been visited by Europeans and not at all since the outbreak of the Great War. It is now practically empty, but before the war tribes of mountaineers could find a scant living by sowing crops on the terraced valleys and by pasturing their hardy sheep and goats on the mountain-sides.