A most diabolical deed

Infanticide and Irish Society, 18501900

Elaine Farrell

Manchester University Press

Manchester and New York

distributed in the United States exclusively

by Palgrave Macmillan

Copyright Elaine Farrell 2013

The right of Elaine Farrell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK

and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

Distributed in the United States exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,

NY 10010, USA

Distributed in Canada exclusively by

UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall,

Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 0 7190 8820 9 hardback

First published 2013

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by 4word Ltd, Bristol

For my parents, Liam and Marie

Contents

I am grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council and Queens University Belfast for the funding that allowed me to carry out this research. I am extremely thankful to Professor Mary ODowd, who supervised the PhD thesis on which this book is based. Professor ODowd has been a constant source of advice and encouragement over the past number of years. I am indebted to her for her assistance.

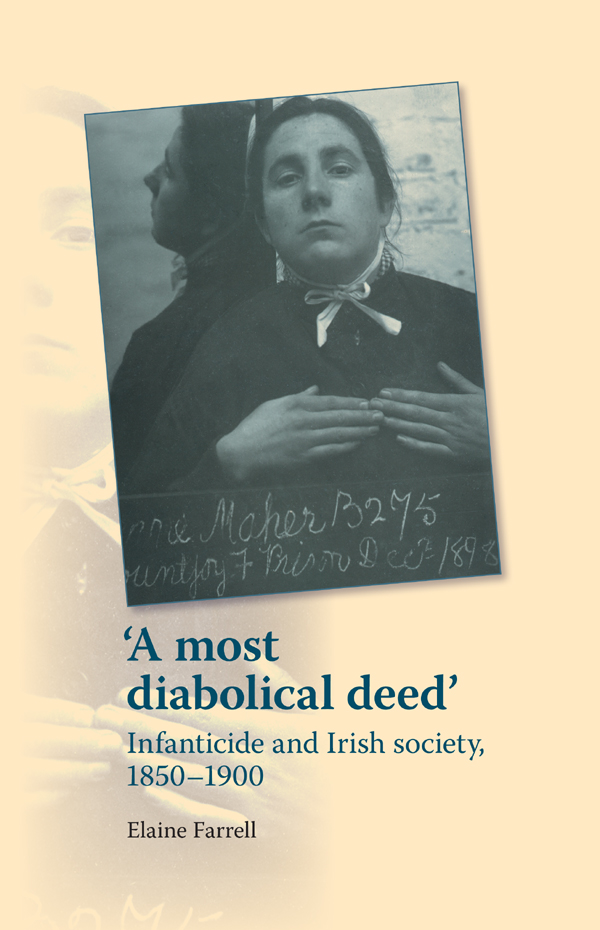

I wish to thank the staff of a number of repositories. I am particularly grateful to the staff of the National Archives of Ireland, especially Catriona Crowe, Brian Donnelly, Aideen Ireland and Gregory OConnor. I am also thankful to the staff of the reading room, in particular, Christy Allen, Robert Coffey, Brendan Crawford, Paddy Ellard, Mick Flood, Brendan Martin, Ken Martin, Dave ONeill and Paddy Sarsfield. I also wish to acknowledge the assistance provided by the staff of the Archives of Tasmania; the Belfast Newspaper Library; the Dublin Diocesan Archive; the Galway County Council Archive; the Garda Museum; the National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin; the National Library of Ireland; the Police Service of Northern Ireland Museum; the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, particularly Graham Jackson; the library at Queens University Belfast; the Representative Church Body Library, Dublin; and the Sligo Reference Library. For permission to publish images, I am thankful to the Director of the National Archives of Ireland, and Brian and Nicole Rieusset.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the dedicated and welcoming staff of the School of History and Anthropology, Queens University Belfast. I am especially grateful to Professor Catherine Clinton, Dr Marie Coleman, Professor Sean Connolly, Dr James Davis, Professor Peter Gray, Professor David Hayton, Dr Andrew Holmes, Professor Liam Kennedy, Dr Chris Marsh and Dr Fearghal McGarry. A number of scholars based at other universities offered advice, insightful and helpful suggestions or encouragement during the research and writing of this book. In particular, I am grateful to Dr Sarah-Anne Buckley, Dr Lindsey Earner-Byrne, Professor Diarmaid Ferriter, Dr Daniel Grey, Professor James Kelly, Professor Maria Luddy, Dr Conor Reidy and Dr Bernadette Whelan.

My extended family and friends are owed gratitude for the encouragement and timely distractions, in particular Julianne Desrochers, Mairead Devaney, Anneliese Dykes, Aaron, Cian, Conor, Eileen and Liam Ryder, and my grandmother, who often wonders when I am going to finish that book about the woman who killed her baby. Dr Shaun McDaid, who led the way, Dr Claire Rush, who proves a daily inspiration, and Dr Ioannis Tsioulakis, who puts up with it all, generously offered to read extracts from this book at various stages. I am thankful for their interest in my research and for their friendship over the past number of years. Finally, I would like to thank my family, my parents, Liam and Marie, and my sisters, Fiona and Deirdre, for lending several hands at various times. This book is dedicated to my parents for their support and encouragement.

References to Crown files in the Nation Archives of Ireland refer to Crown files at assizes unless otherwise stated.

AOT | Archives of Tasmania |

CIF | Criminal Index File |

CRF | Convict Reference File |

CSO OP | Chief Secretarys Office Official Papers |

DMP | Dublin Metropolitan Police |

GPB | General Prisons Board |

GPO | Government Prisons Office |

HMP | Her Majestys Prison |

ICR | Irish Crimes Records |

NAI | National Archives of Ireland |

NLI | National Library of Ireland |

Pen. | Penal Files |

PSNI | Police Service of Northern Ireland |

RIC | Royal Irish Constabulary |

TNA | The National Archives |

Katie Connors rose just after six oclock on the morning of 13 September 1900. She worked as a domestic servant for Catherine Coad in Ballymaclode, County Waterford. A second servant, Bridget Power, had been employed in the house since February. Power had retired to bed earlier than usual on the previous evening due to the onset of a cold. She had been brought hot brandy in bed by her employer and later that evening, had been offered a cup of hot tea by her fellow servant. On account of Powers illness, Connors undertook her co-workers task of lighting the stove on the following morning. She also brought a warm drink upstairs to her sick colleague. Power, however, was dressed by that stage and followed Connors down to the kitchen. The two women had their breakfast and made a start on their daily tasks. Power set out to milk the cows and Connors began to clean each of the rooms in the house.

The small bedroom that Connors shared with Power was the last room to be cleaned that morning. Katie Connors swept out the room. She picked up her hat and went to tidy it away in the bedroom cupboard. On opening the cupboard, she noticed a rolled-up sheet. Curious, she unwrapped the bundle and uncovered the dead body of a newborn female infant. Connors reported the discovery to her employer Catherine Coad, who in turn sent a message to her husband. The local constable was subsequently summoned to the house in Ballymaclode. Power would later admit to her employer that she had put her fingers in the babys mouth to stop her crying when she had heard Connors coming up to the bedroom on the previous night.1