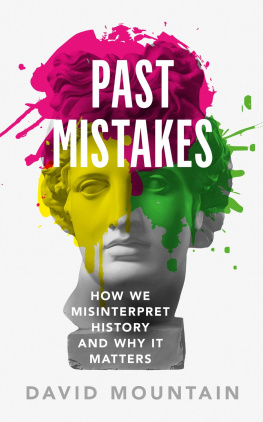

S tanding in the Ashmolean museum I have the sudden urge to laugh. Given that Ive come to Oxford to see an exhibition of classical sculpture, this might seem odd. But the busts and statues before me arent the dead-eyed marble creations weve come to associate with the ancient world. Rather, theyre plaster reconstructions of what the artworks might have looked like when they were first created over 2,000 years ago complete with their original, very loud, coats of paint.

The effect is startling, to say the least. Cold marble is transformed into warm skin tones. White robes become vibrant costumes. Bronze figures stare back at you with disconcertingly lifelike eyes. Particularly alarming is a sculpture of Paris, the archer and playboy prince from Greek mythology. In the marble original, carved some 2,500 years ago on the island of Aegina and now faded to a dirty white, he looks noble and deadly; in the replica, dressed in a luridly patterned outfit of yellow, blue, green and red, he looks like hes just graduated from Clown College. I cant help but snigger.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about these reconstructions, however, is that they probably would have been utterly unremarkable to inhabitants of the ancient Mediterranean. We dont know the exact tints or techniques they employed, but an increasingly sophisticated array of ultraviolet, infrared, X-ray and chemical analysis tells us for certain that classical sculptures were almost never left unadorned. In fact, just about everything the Greeks and Romans could slather in paint or bedeck in jewels, they did. The 40-foot statue of Zeus in Olympia one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World was garishly clad in gold, ivory, gemstones and brightly painted wood. The Parthenon once housed a similarly gigantic and gaudy statue of the goddess Athena until it burned down sometime in the 3rd century CE. Even the Parthenon itself was brightly decorated with colourful friezes. And while theres evidence that some artists aimed for a naturalistic finish, with realistic skin and hair tones, its clear that others opted for all-out psychedelia: archaeologists have uncovered the remnants of green horses and blue-maned lions. The limestone remains of a three-headed monster discovered at the Acropolis is known to have had black eyes, yellow skin and blue beards.

The Greeks and Romans were by no means unique in their love of colour. A wide range of ancient and historic cultures from the Japanese to the Vikings to the Aztecs were united by their appreciation of what archaeologists call polychromy: the use of colour in art and architecture. Chinas Terracotta Warriors were once brightly painted with greens, reds, violets, pinks, whites and blues. Mesoamerican cultures like the Maya decorated their sculptures, structures and even pyramids in blocks of red, blue, yellow, pink and green. The castles of medieval Europe, in contrast to the dark and dingy lairs of popular imagination, were stuffed with brightly coloured furniture and wall hangings.

St Bernard may not have approved, but there was sound reasoning behind the carnivalesque colour schemes of his contemporaries and others. Bright hues helped friezes and sculptures mounted high up on temple walls to be clearly visible. Artworks often carried religious or political meaning, and distinctive colours conveyed a more intelligible message than a block of monochrome marble. Whats more, in the days before the mass production of paints, colour was expensive. Pigments had to be extracted from such obscure sources as tropical plants, toxic metals and the ink sacs of cuttlefish. The bright blue details on Tutankhamuns funerary mask came from the mineral lapis lazuli, which was mined only from a remote valley in what is now Afghanistan and was more valuable than gold. The gaudier the art, therefore, the wealthier the patron.

Such motivations become lost or obscured in the sterilised scholasticism of the art gallery or exhibition hall. As a result, attempts to recapture lost polychromy, as with the exhibition at the Ashmolean, can be jarring to those who have long admired the austerity of classical sculpture or the solemnity of Gothic architecture. When an ancient Egyptian statue of the falcon-headed god Horus was recreated in its original hues by the British Museum in 2011, complete with big cartoon eyes, the result bore an unsettling resemblance to Sesame Streets Big Bird. When a famous statue of the Roman Emperor Augustus was reconstructed with violently crimson clothes and bright scarlet lips, one shell-shocked historian claimed to suffer trauma when he saw it.

Why is all this such a shock to us? If the past really was an eye-watering kaleidoscope of colour, as archaeologists are insisting, then why isnt such information more widely known? Its not as if the ancient Greeks were being coy about their love of colour. The tragedian Euripides mentioned it in a number of his works, for instance. Look! cries a character in his play Hypsipyle, cast your gaze upward, and marvel at the painted sculptures in the gable! He even has Helen of Troy, sick of her dangerously good looks, wishing she could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect, the way you could wipe colour off a statue. The sculptor Praxiteles shared this view, acknowledging that his favourite creations were those which had been painted by the artist Nikia. There are even depictions on Greek vases of artists painting statues.

The first explanation is simple enough: colour fades. Paints exposed to the elements, like those at the Acropolis, gradually bleach and peel. Artworks that end up buried underground are often better preserved, although they can rapidly deteriorate once brought to the surface. A visitor to the Acropolis in the 1880s noted that a newly-unearthed artefact would often be surrounded by a little deposit of green, red and black powder which had fallen from it. When the Terracotta Warrior pits were first opened in the 1970s, remaining traces of paint began flaking off the statues within minutes due to the changing humidity of the tomb.

Its the second explanation, however, thats far more interesting: classical sculpture is monochrome because we want it to be. When the remains of ancient Rome were first uncovered in the 15th century by which time much of their original hues had vanished it became widely accepted that they had always been white. Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo sought to recapture the majesty of classical sculpture by creating unadorned statues. The more painting resembles sculpture, the better I like it, the old master opined, and the more sculpture resembles painting, the worse I like it.

So when evidence for ancient polychromy began to creep into academic circles during the 18th and 19th centuries, archaeologists and artists, having invested heavily in the myth of classical whiteness, resisted. Facts were forced to fit theory. Remnants of paint were dismissed as dirt or soot. Greek statues with pigments still intact were attributed to other, less revered civilisations, such as the Etruscans. Many archaeologists actually scrubbed any remaining traces of colour off statues in order to restore the marbles gleaming whiteness. The renowned chemist Michael Faraday subjected marble friezes from the Parthenon to abrasive grits, alkaline solutions and even nitric acid in an attempt to recover that state of purity and whiteness which they originally possessed.

Even today, more than 40 years after ancient polychromy was finally accepted by the majority of archaeologists, its a subject that can still surprise. Depending on your perspective, the image of classical sculpture slathered in bright paint can be funny, shocking or even upsetting. It will take time and effort to see past centuries of collective colour blindness and shake off the myth of a monochrome past.