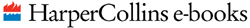

The summer monsoons had begun; scattered but heavy rain swept across the sky, dropping from the thick clouds that blackened the night. On the eastern rim of Asia, it was the early hours of Sunday, June 25, 1950, and most of the oriental world was asleep. Here and there, in the jungles of Malaya or the hills of Indochina, there was furtive movement where British soldiers or French Legionnaires tried to stay awake and alert for attack by Communist guerrillas. But it was quiet in the Philippines, where the Communist Hukbalahap guerrillasHuks as they were calledhad temporarily settled down. The British garrison watched the Communists over the border of the New Territories from Hong Kong, but having just won a civil war, the new Chinese regime did not wish to disturb one of their major channels for supplies from the western world. In Japan, the American occupation forces were asleep, except for those unfortunate few who had drawn duty for the weekend.

On the other side of the Sea of Japan, in the southern part of the Korean peninsula, an area styled the Republic of Korea, all was serene. The republic extended northward to an artificial line, the 38th parallel of latitude. Along its southern edge, the few soldiers on front-line duty huddled in their bunkers or under their ponchos, waited for the rain to stop or dawn to break or their reliefs to arrive, thought of home or girlfriends and wished they were somewhere else.

North of the parallel, it was another country, the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, and here, of all places on that warm, dark summer night, it was not quiet at all. The north, in contrast to the somnolent south, was a beehive of last-minute activity. Infantrymen checked their weapons and shuffled forward to their assault positions; gunners looked at watches, studied firing coordinates, and glanced at their watches again. Inside their steamy tanks, drivers revved engines, listening to the throaty roar; the tanks squatted on their heavy treads, waiting to be unleashed.

Finally the waiting was over. Starting about 0400, the dying hour of the night, the artillery roared out. From west to east along the parallel there was a rippling line of gunfire, so that it took about an hour before the action was general. Beneath the hurtling umbrella of shells, the Communist tanks and infantry surged forward. In the west they hit first, against isolated units on the Ongjin peninsula, cut off by water from the rest of South Korea. To the east, as the attack gathered momentum, the North Koreans met only scattered resistance. Nothing but outposts held the positions immediately below the parallel; the main South Korean line was something from ten to thirty miles back, and even then it was not held with any real strength. The South Koreans had no tanks of their own, few heavy weapons, and, most important as events developed, nothing that would stop a North Korean tank.

In Seoul, the capital of South Korea, there was a small American military advisory group; it received word of the attack on the Ongjin peninsula about 0600, two hours after it had begun. More bad news soon followed, and by 1000 it was clear that a full-scale invasion was in progress. Messages began to flicker back up the chain of command. At midmorning, American Ambassador to Korea John J. Muccio sent a report to the Department of State in Washington; an hour earlier his military attach had sent a similar message to the Department of the Army, and then throughout the day amplifying calls and telegrams went out, many of them from the U.S. Air Force control group stationed at Kimpo airport near Seoul. At the same time as the first official alarms reached Washington, press reports of the invasion began to arrive over the wire services of the news agencies. It was early Saturday evening on the East Coast of the United States, just in time to make the Sunday papers.

Washington was caught by surprise. As is often the case, government intelligence agencies had been trapped between the rock of capabilities and the hard place of intentions. They knew North Korea possessed the capability to attack South Korea, but that meant relatively little, particularly since most other Communist countries had similar capabilities with respect to their non-Communist neighbors. The important question had not been whether they could do it but rather whether they intended to do it. In June 1950 there seemed to be far more likely trouble spots than Korea, for at that time, the western world had a lot to worry about, most if it more pressing than an out-of-the-way country on the edge of Asia.

Now, suddenly here was where the action was, where, in the constantly repeated phrase of the day, the Cold War had turned hot. President Harry S. Truman was away from Washington, at his hometown of Independence, Missouri. He flew back to the capital on the afternoon of the 25th, and at a conference that night at Blair House, across the street from the White House, which was being redecorated, he and his advisers began the series of decisions that would ultimately commit American ground troops to fight in Korea. The same day, the Security Council of the United Nations declared North Korea a disturber of the peace and called upon member nations to assist the Republic of Korea in resisting invasion. In response to this, American planes and ships were soon in action over and around the Korean peninsula. It was almost inevitable that they would shortly be followed by American ground forces.

The United Nations peace actionfor it never was declared to be a warso suddenly begun lasted for three years and one month, until July 1953. In it served troops from the Republic of Korea, the United States, and seventeen other member states of the United Nations, on the one side; and troops from North Korea and Communist China and almost certainly some advisers from Soviet Russia on the other side. Billions of dollars were spent, hundreds of thousands of lives lost or altered forever, in a conflict of shadowy nuances, subtle and infuriating limitations, and ambiguous results. A generation after it ended, the question students most often ask of it is: Was this really necessary? But in 1950 the questions were more naive than that. Americans, greeted with the advent of war for the second time in a decade, were asking: Why are there U.S. troops in Korea, and how did they get there? Indeed, most Americans, including many who would die there, did not even know where Korea was.