I

I am sure that there is no one who goes to London for the first time, no matter how hurried he may be, who does not try to visit at least three placesthe Tower, Westminster Abbey, and St. Pauls Cathedral.

Of these three places, two are churches; but they are churches that are so connected with the history of our nation that they almost seem to stand at the heart of the Empire.

Their stories are linked together in a curious way, and yet they are quite distinct. As someone has said, Westminster Abbey was ever the Church of the King and Government; St. Pauls was the Church of the Citizens.

When we come to study the history of Cathedrals, we find the way in which they came to be built is pretty much the same in most cases. A little church was raised to the glory of God, and a monastery was founded beside it, which became the home of a community of monks or nuns, ruled over by an Abbot or Abbess; and the church was known as the Abbey Church.

Then by-and-by, sometimes not till quite late, as at St. Albans, a Bishops Stool was placed there, and the Abbey became a Cathedral.

But in the case of St. Pauls Cathedral it is quite different. It was built for a Cathedral from the first. Its builder, instead of adding a monastery to it, as was usually done, built a monastery having its own Abbey on a little Island which stood in some marshy ground on the banks of the Thames, about a mile away.

This Island was called Thorney Island, and the Abbey Church was dedicated to St. Peter, but soon it began to be spoken of as the West Minster, or Westminster Abbey, by which name we know it to-day.

This was how it all came about. In the time of the early Britons there were Christian churches scattered up and down the land, and it is almost certain, from stones that were dug up when the foundations of the present Cathedral of St. Paul were being laid, that in those far bygone days a little church stood on the Hill of Ludgate, in the centre of Roman London. But, as you know, the Roman legions were recalled to Rome in A.D. 410 to help the soldiers there to drive back the vast hoards of Goths and barbarians who were pouring down from the north-west upon Italy; and when they were withdrawn from Britain, there were not enough fighting-men left to protect her shores from the next enemies who threatened her.

These were the Jutes, the Angles, and the Saxons, fierce and heathen warriors who came from Jutland and from Germany, and landed on our coasts.

They conquered the British, and rapidly forced their way inland, ravaging and pillaging wherever they went; and in the confusion and misery that followed, Christianity was completely swept away for a time, to come again with St. Augustine and St. Columba some two hundred years later. You know too, perhaps, that when St. Augustine came to Canterbury and began to preach the Gospel there, the King of Kent, Ethelbert by name, soon became a Christian. This King Ethelbert was a very powerful monarch, and he was Overlord of the King of the East Saxons, who chanced to be his nephew, and who lived in what we now call Essex. Now, while St. Augustine preached to the men of Kent, a friend of his, named Milletus, preached to the East Saxons. And when at last their King became a Christian, his uncle Ethelbert suggested that, as Kent had its Bishop of Canterbury, with his Cathedral Church, it would be a good thing for the Kingdom of the East Saxons to have a Bishop of its own who would have his Cathedral Church also.

So, as London was the Capital of the East Saxons, he proposed to help King Siebert to build a church there; and Augustine, only too glad to find that the Faith was spreading, said that Milletus should be its first Bishop.

It was in this way that the first Cathedral of St. Paul was built, and, as we have seen, Siebert also founded the church and monastery of Westminster.

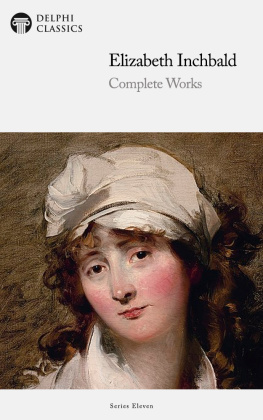

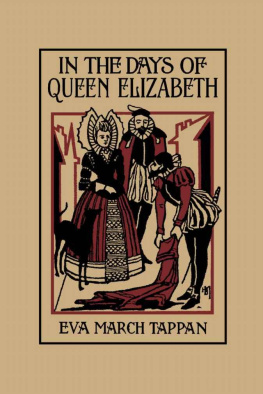

KING JOHN SIGNING MAGNA CHARTA. PAGE 18.

AFTER THE PAINTING BY ERNEST NORMAND IN THE ROYAL EXCHANGE, LONDON

By permission of the artist.

Now, although their King had been baptized, and had built two churches in their midst, the people of London did not want to become Christians; they were pagans, and were quite content to worship Thor and Odin, the gods of the tribes of the North. So for a long time the good Bishop Milletus preached to them in vain; and far away in Rome, Pope Gregory, who had hoped that the new Cathedral in London would become what we call the Metropolitan Church of Englandthat is, the church where the Archbishop has his thronewas sadly disappointed, and had to become accustomed to the idea of Canterbury, which was a far less important place than London, having that honour.

Indeed, for a time it seemed as though, in spite of Church and Bishops, the new religion would be driven out. Ethelbert died, and so did his nephew Siebert, and the Kings who succeeded them either went back altogether to their pagan worship, or tried, as an East Anglian King did, to worship Thor and Odin and Christ all at the same time. I will tell you just one story about those troubled days, and it will show you what a terrible struggle went on between Paganism and Christianity, and how much we owe to these brave men, priests, and Abbots, and Bishops, whose names are almost unknown to us, on whom rested the responsibility of maintaining the Faith in England, and of whom, to their honour be it said, hardly one failed.

One day Bishop Milletus was administering the Holy Communion in his church to the little congregation of Christians who still remained true to what he had taught them. It is probable that the altar stood then just where the high-altar in St. Pauls stands to-day. Only the church would be much smaller and plainer, and the door would be locked to prevent unbelieving pagans entering and disturbing the service by irreverent jeering and laughter. Suddenly a loud knocking was heard, then the crash of falling wood. The young King and his friends had chanced to be passing, and, in a moment of heedless excitement, had determined to visit the Christians church, and see what amusement they could get there. Angry at finding the door locked against them, they had broken it down without further delay. Up the aisle strode the King, followed by his mocking companions, to where the old Bishop was engaged in distributing the consecrated Bread to the kneeling communicants. In those days white bread was a rarity, most of it being dark-coloured and unwholesome; and this white bread that was used for the Holy Communion was the whitest and purest of all; for, in order that it should be so, pious people, even the clergy themselves, used to grind the meal carefully with their own hands, and bake it into loaves, and bring it to the church as their offering.