First published 1992 by Ashgate publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

7 11 Third Avenue, New York, NY 1001 7, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Loades, D. M.

The Tudor Navy an administrative, political, and military history / by David Loades.

p. cm. -(Studies in naval history)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-85967-922-5

1 Great Britain History, Naval Tudors, 14851603. 2. Great Britain. Royal Navy History. I. Title. II. Series.

DA86. L63 1992

359.00941-dc20

9 143374

CIP

ISBN: 978-1-3152-3672-8 (hbk)

contents

preface

It seems a long time ago that Nicholas Rodger invited me to write this book, and my first gratitude is to him for his patience. As will soon become apparent to the reader, I have come to the Tudor navy via other aspects of Tudor history, and not via other periods of naval history. I make no apology for this, because the navy was an integral part of royal government, as well as being closely related to the developments of the commercial and maritime communities. The tradition of naval history has tended to be isolationist, and that makes for unnecessary difficulties of understanding. This is also a general work. Although based partly on my own researches, it makes no claim to technical originality, aiming instead to present a profile of the sixteenth-century navy which may be different from that customarily received. Above all it aims to place the navy in its proper political and administrative context.

In the course of the last four years, I have accumulated many obligations and debts of gratitude, apart from that to my long suffering General Editor. First to the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford, for electing me to a visiting Fellowship in the academic year 19889; secondly to the staff of the Bodleian Library, the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, and the Public Record Office, where the bulk of the research was undertaken; and thirdly to the British Academy for a grant to cover travel and other expenses. My colleagues and students have also had to bear with me during the period of gestation, when my thoughts were on victualling rather than the Pilgrimage of Grace or the rebellion of the northern earls. But above all my gratitude is due to my wife, for her constant encouragement and support among the innumerable preoccupations of running her own business. Her example in diligence and self-discipline has been an inspiration.

DL

Abbreviations

| APC | Acts of the Privy Council |

| BL | British Library |

| AGS | Archivo General de Simancas (Spain) |

| CPR | Calendar of the Patent Rolls |

| Cal. Scot. | Calendar of State Papers relating to Scotland |

| Cal. Span. | Calendar of State Papers, Spanish |

| Cal. Ven. | Calendar of State Papers, Venetian |

| EHR | English Historical Review |

| Hall, Chronicle | The Union f the two noble and illustre families of York and Lancaster, by Edward Hall |

| L and P | Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic. of the reign f Henry VIII, ed. J. Gairdner et al. |

| M M | Mariners Mirror |

| TRHS | Transactions of the Royal Historical Society |

| PRO | Public Record Office |

(for details see Bibliography)

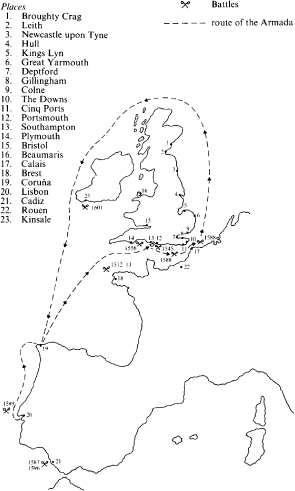

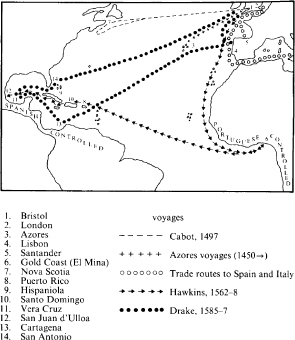

English expansion into the Atlantic, 14501600

1

introduction

The sovereignty of the seas, wrote Sir John Borough in 1633, was the most precious jewel in his Majesties crown and the principal means of our wealth and safety.1 Borough was arguing in favour of a mare clausum, and like many antiquarian lawyers of his generation, felt compelled to trace his sources back to Julius Caesar. The Saxon King Edgar, he declared, had maintained a navy of 400 ships to assert his authority at all four corners of his realm, and he went on to describe how John, Edward I and Edward III had defended this same ascendancy. In the absence of any agreed definition of territorial water, it is not quite clear how far Boroughs concept of sovereignty extended. He wrote of Edward IV granting licences to foreigners to fish off the Yorkshire coast, and of Queen Mary selling fishing rights in Ireland to her husbands subjects. But his main concern was with the Narrow Seas where, he claimed, all other ships vaile Bonnet in acknowledgement of English superiority to this day. The main political thrust of Boroughs treatise was against the Dutch, who were getting rich and immensely strong at sea by taking 300 000 worth of fish a year out of English waters without either fee or licence an argument which echoes that of John Dee over sixty years before.2 Queen Elizabeth had not been as remiss as Charles I:

I remember that those of Hamburg and other Easterlings (though in amitie with us) in the late reign of Queen Elizabeth of famous memory were notwithstanding stayed from passing through our seas towards Spain, and good prize made of all other nations that attempted to do the like.

What he did not remember, or did not choose to remember, was that the actions of the English navy at that time had very little to do with the assertion of abstract concepts of sovereignty and everything to do with waging war on Spain. Nevertheless his point was valid. Authority over the sea, like authority over colonial territories, could only be claimed if it could be exercised, and what concerned him was less Hugo Grotiuss doctrine of mare liberum than the power of the Dutch navy. Whatever may have happened in the time of King Edgar or Edward III, the Elizabethan navy had controlled the Channel, and effectively extended the authority of the English Crown beyond the shores of the realm.

Sea power had always been expressed in royal or imperial fleets, but such fleets had been the personal creations of the monarchs who had led or operated them. The Tudor navy, on the other hand, was an aspect of the state, and its history has to be seen in that connection. Its establishment and early development was an act of political will which had very little to do with the maritime history normally associated with it. Only after the middle of the century did the two begin to converge, as naval strategy assumed an oceanic aspect, and mercantile entrepreneurs acted as an auxiliary navy. It is consequently a serious mistake to study the Tudor navy in isolation from other facets of government, with which it had much in common. The kings ships, like his artillery, were an expression of his power. Dependence upon noble support was second nature to any medieval king, and the fact that the Earl of Warwick had more ships than Edward IV does not seem to have taught that highly conservative monarch any urgent lessons. Most of Edwards ships, when he needed them, came from the port towns, like the cash which he borrowed from the citizens of London when his land revenues were slow to arrive. Edward, relying upon his personal ascendancy, did not object to this kind of dependence, but Henry VII set out systematically to reduce it. By increasing his revenues he reduced his reliance on short-term loans, and on grants from parliament. By taking more gentlemen directly into his service he made himself less dependent upon the nobility. By building two large warships and constructing an embryonic naval base at Portsmouth he lessened his need to call upon the ships of his subjects. In spite of the contrast in their personalities, Henry VIII followed his fathers policies in many respects. Less suspicious in his relations with his nobility, he nevertheless continued to build up his affinity at a lower level, a strategy urged upon him, and largely executed, by Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell, his successive chief ministers. The result was a steady growth in the importance of royal commissions of all kinds, which were largely served by knights and gentlemen. Unwilling to rely upon personal or