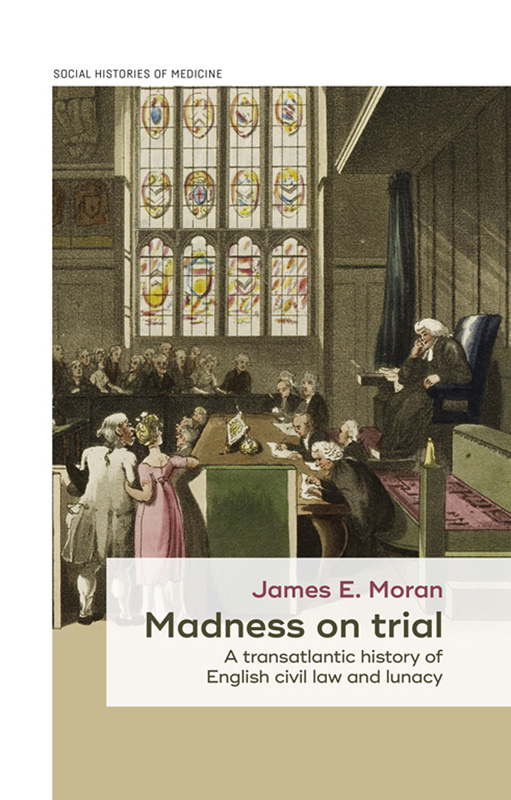

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF MEDICINE

Series editors: David Cantor and Keir Waddington

Social Histories of Medicine is concerned with all aspects of health, illness and medicine, from prehistory to the present, in every part of the world. The series covers the circumstances that promote health or illness, the ways in which people experience and explain such conditions and what, practically, they do about them. Practitioners of all approaches to health and healing come within its scope, as do their ideas, beliefs and practices, and the social, economic and cultural contexts in which they operate. Methodologically, the series welcomes relevant studies in social, economic, cultural and intellectual history, as well as approaches derived from other disciplines in the arts, sciences, social sciences and humanities. The series is a collaboration between Manchester University Press and the Society for the Social History of Medicine.

Previously published

The metamorphosis of autism: A history of child development in Britain Bonnie Evans

Payment and philanthropy in British healthcare, 191848 George Campbell Gosling

The politics of vaccination: A global history Edited by Christine Holmberg, Stuart Blume and Paul Greenough

Leprosy and colonialism: Suriname under Dutch rule, 17501950 Stephen Snelders

Medical misadventure in an age of professionalization, 17801890 Alannah Tomkins

Conserving health in early modern culture: Bodies and environments in Italy and England Edited by Sandra Cavallo and Tessa Storey

Migrant architects of the NHS: South Asian doctors and the reinvention of British general practice (1940s1980s) Julian M. Simpson

Mediterranean quarantines, 17501914: Space, identity and power Edited by John Chircop and Francisco Javier Martnez

Sickness, medical welfare and the English poor, 17501834 Steven King

Medical societies and scientific culture in nineteenth-century Belgium Joris Vandendriessche

Managing diabetes, managing medicine: Chronic disease and clinical bureaucracy in post-war Britain Martin D. Moore

Vaccinating Britain: Mass vaccination and the public since the Second World War Gareth Millward

Copyright James E. Moran 2019

The right of James E. Moran to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN978 1 5261 3303 8hardback

First published 2019

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

The impetus for this book came in the mid-1990s when I was digging around in the New Jersey State Archives at Trenton. I was hoping to conduct research on the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum. However, at the time of my visit, documents relating to asylum development in New Jersey were difficult to access. Upon further inquiry, the helpful archivists at the Trenton archives suggested that I take a look at a collection of manuscripts that had been deposited, unprocessed, in several boxes that were destined for recycling. These files proved to be a rare treasure trove of civil legal documents relating to madness in New Jersey, dating from the 1790s to the early twentieth century. But it took time years in fact to unpack them, literally and figuratively. Although there is still much historical potential in these trials of madness awaiting the next brave soul who relishes reading thousands of hand-written documents at the Trenton archives, I think that I have made myself familiar enough with them to articulate in this book the arguments that I wish to establish about their importance. The origins of these New Jersey civil trials of lunacy lie in English precedent, and this fact encouraged me to add to the good work of a few other historians by writing chapters on the formation and development of lunacy investigation law into what, I argue, was the most important and enduring formal response to madness in England. Finally, the connections between the development of lunacy investigation law in England and in New Jersey required a consideration of this body of law in transatlantic imperial context. This, in a nutshell, is the background and rationale for the book.

As befits a book that took many years to complete, I owe a debt of gratitude to a great many individuals. In my initial excitement about the New Jersey lunacy trial documents, Susan Houston challenged me to realise their potential. I was encouraged by Charles Rosenberg to keep pushing at what he termed the un-asylum history of madness that these sources seemed to represent. Archivists Betty Epstein and Joseph Klett at the New Jersey State Archives have given me good counsel about archival collections and have been wonderfully open minded about keeping and preserving hitherto unappreciated manuscript sources. Many conference presentations and many discussions with historians of mental health about lunacy investigation law and madness have helped to clarify the analysis in this book. In particular, I would like to thank Jonathan Andrews, Barbara Brookes, Erika Dyck, Waltraud Ernst, Marjory Harper, James Muir, Thomas Muller, Thierry Nootens, Isabelle Perreault, Jim Phillips, Andrew Scull, Len Smith, Sally Swartz, Marie-Claude Thifaut, Barbara Todd and Leslie Topp. The long-distance and long-term friendship of Akihito Suzuki, a pioneer historian of English lunacy investigation law, has been of major benefit to my thinking on the subject. Closer to home, at the University of Prince Edward Island, I am grateful for the support of colleagues Ian Dowbiggin, Scott Lee, Edward MacDonald and Sharon Myers who kept politely asking, so, how is the book coming along? Undergraduate researchers Cassandra Armsworthy, Kathryn (Morell) Doucette, Jennie (Palmer) Mutch, Norah Pendergast and Marilyn Sweet gave excellent assistance at earlier stages of the research. Their professional and personal successes since graduation are a reminder of their good research skills and also of the time that has passed in my efforts to complete the book!

David Wright has been instrumental in my musings about how to write a book about the history of lunacy investigation law. This has entailed many conversations, house visits, coffee-shop debates and discussions, along with his willingness to read and review several draft chapters of this book. My father, Jim Moran, has read every word of every chapter with his professional editorial eye. For this, and the wonderful academic conversations that ensued, I am grateful. This book has benefited from some crucial early-stage funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and from Associated Medical Services. I would also like to acknowledge the good work of editorial staff at Manchester University Press and the insightful suggestions of the anonymous referees.