BLACK ELK SPEAKS

BLACK ELK SPEAKS

Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the OGLALA SIOUX

THE PREMIER EDITION

as told through John G. Neihardt

(Flaming Rainbow)

Annotated by Raymond J. DeMallie

with illustrations by Standing Bear

Copyright 1932, 1959, 1972

by John G. Neihardt

Copyright 1961,2008

by the John G. Neihardt Trust

Copyright 2008

State University of New York Press

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

First Excelsior Editions book printing:

2008

Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University ofNew York Press, Albany

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Black Elk speaks: being the life story of a holy man of the Oglala Sioux / as told through John G. Neihardt (Flaming Rainbow); annotated by Raymond J. DeMallie with illustrations by Standing Bear.

p. cm.

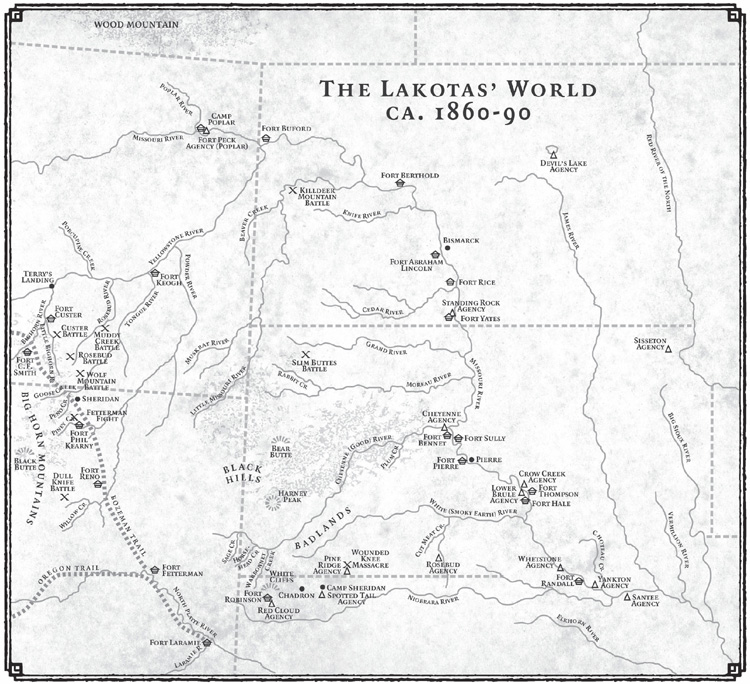

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4384-2540-5 (pbk.: alk.paper) 1. Black Elk, 1863-1950. 2. OglalaIndiansBiography. 3. Oglala IndiansReligion. 4. Teton Indians. I. Neihardt, John Gneisenau, 1881-1973. II. DeMallie, Raymond J., 1946

E99.Q3B482008

978.0049752440092dc22

[B]

2008038002

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

What is good in this book

is given back

to the six grandfathers

and

to the great men of my people

Black Elk

Contents

Illustrations

Drawings by Standing Bear

18. Horse Dance (Chief): East

Maps

Maps

Preface to the 1932 Edition

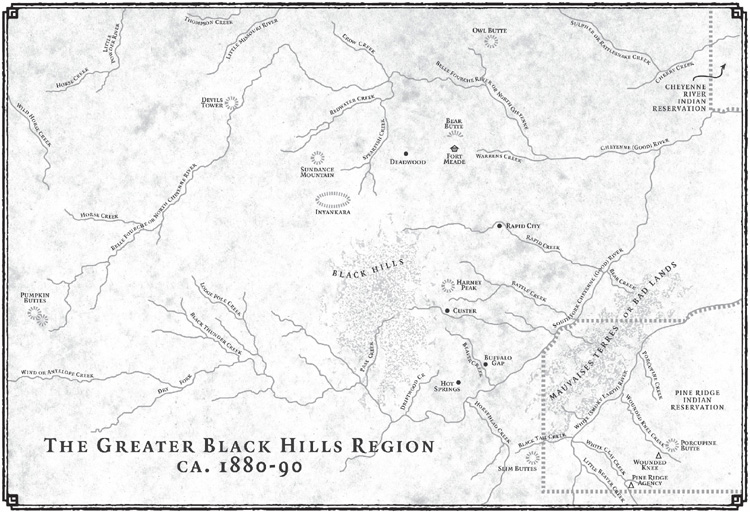

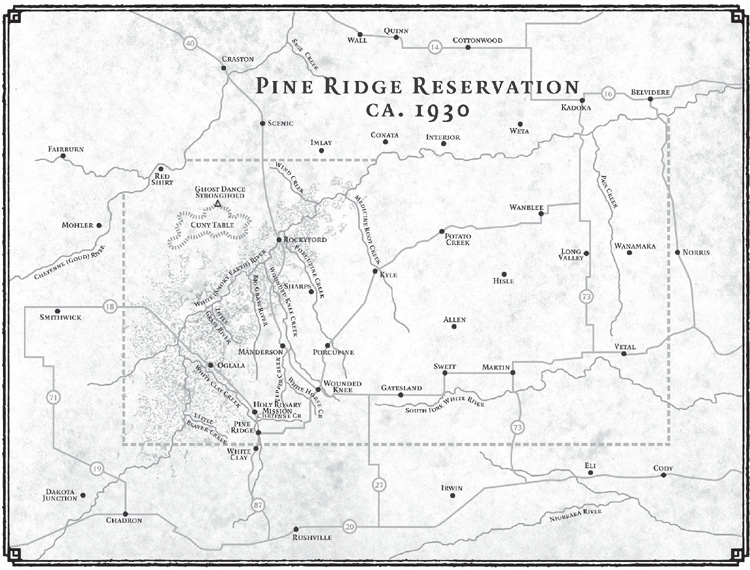

The first time I went out to talk to Black Elk about the Ogalala Sioux, I found him sitting alone under a shelter of pine boughs near his log cabin that stands on a barren hill about two miles west of Manderson Post Office.

I had learned that Black Elk was related to the great Chief Crazy Horse and had known him intimately; so, in company with my son and an interpreter, I went to see him, expecting no more than the satisfaction of exchanging a few words with one who had, not once but many times, seen Shelley plain. Nor did I feel certain of even so much; for, on the way, my interpreter said that he had taken another writer to Black Elk that morning without success. I can see that you are a nice-looking woman, the old man had remarked, and I can feel that you are good; but I do not want to talk about such things.

Black Elk paid me no compliments, but he talked all that August afternoon, save for frequent brooding silences when he sat hunched up, with folded elbows on his knees, staring upon the ground with half blind eyes.

It was not of worldly matters that he spoke most, but of things that he deemed holy and of the darkness of mens eyes. Although my acquaintance with the Indian consciousness had been fairly intimate for more than thirty years, the inner world of Black Elk, imperfectly revealed as by flashes that day, was both strange and wonderful to me.

The following year, in company with my daughters, Enid and Hilda, I returned to Black Elks home for an extended visit, that he might relate his life story to me in fulfillment of a duty that he felt incumbent upon him. The nature of that duty as he conceived it will be apparent to readers who may approach the book in no condescending mood as of a civilized person more or less curious about the savage mind, but with the humble desire of one groping human being to understand another and perhaps to learn a little more in a world where so very little can be known. Such a reader should find much in Black Elks consciousness for earnest pondering, especially in view of the present state of affairs throughout the whole scale of human values as our civilization has dealt with them.

But even those who seek merely to be entertained need not fear to listen when Black Elk speaks. He has been a participating witness to various stirring events, both in the physical and in the spiritual world, and he tells of these with a thoroughly unself-conscious simplicity that makes for easy reading. If at times his insights and poetic reaches approach sublimity, it will be granted that upon occasion his sense of humor is sufficiently lively to keep him in close touch with his fellow men.

and yet during our extended visit with him and his friends, he was never slow to enter into any sport that might make my daughters happier, and he could remember many a funny story and good joke to liven the spirits of our party in our duller moments. He could enter into a game of hoop-and-spear with the gusto of a care-free boy, and he would dance half the night away with us under the stars to the booming of the drums and the strangely beautiful songs that he knew in his youth.

When I first met Black Elk he was almost blind. Recently he has become totally so, a fact of which he informed me quite casually and apparently without sense of affliction. Is he not thus released from the darkness of the eyes, and so a little nearer to his visioned world of reality?

Black Elk is illiterate; but thoughtful readers will allow that he is none the less an educated man in the fine sense of a term that sometimes seems to have lost its vital meaning for us in this excessively progressive age. For how may an educated man be described correctly, save by saying that in his consciousness racial experience has been recapitulated to build a rich personality? And surely in Black Elk we find the culture of his people in full flower.

I would suggest that this narrative should not only appeal to average human beings with a normal interest in other human beings, but that students of social theory, of essential religion, and of psychical research especially, should find the book worthy of consideration. Incidentally, those who seek for meaning in the visions, particularly the Great Vision, are likely to be repaid for the effort.

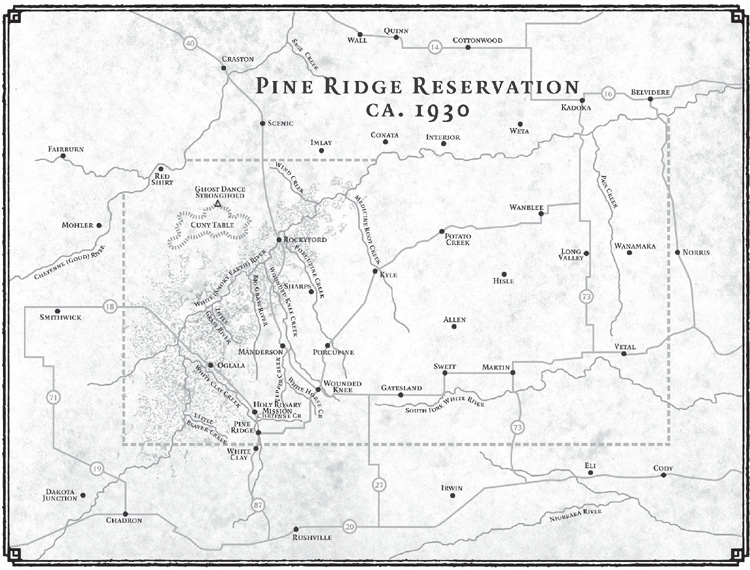

I wish to express gratitude to my friends among the Ogalala Sioux for helping me in many ways, and for their human kindness, although most of them will never learn that I have done so. I am especially indebted to Benjamin, son of Black Elk, for his painstaking and efficient service as my interpreter through many days, and to my daughter, Enid, for the voluminous stenographic record of the conversations out of which this book has been wrought as a labor of love. Government officials were generous in helping me, and I have good reason to be grateful to Secretary of the Interior, Ray Lyman Wilbur; Malcolm McDowell, Secretary of the Board of Indian Commissioners; Flora Warren Seymour, a member of the Board; and to B. G. Courtright, Field Agent in Charge at Pine Ridge.

Next page