Acknowledgments

A whole citys worth of people and institutions helped make this book possible. The research was supported by generous grants from the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Program, the German Academic Exchange Service, the Mabelle McLeod Lewis Memorial Fund, the University of California, Berkeley Institute for International Studies John Simpson Memorial Fellowship, the Charlotte W. Newcombe Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship, the Social Sciences Research Council Eurasia Dissertation Fellowship, the Berlin Program for Advanced German and European Studies Fellowship, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) Research Fellowship, the Harriman Institute at Columbia University, and the Kennan Institute of the Woodrow Wilson Center for Scholars. The Department of History, Institute for Slavic, Eastern European, and Eurasian Studies, and the Program in Soviet, Eastern European, and Eurasian Studies at Berkeley helped a midwestern migr feel at home.

During research trips to Russia, Germany, Poland, and Ukraine, I received excellent guidance from numerous institutions. The archivists at the State Archive of Kaliningrad Oblast (GAKO) and the State Archive of Contemporary History of Kaliningrad Oblast provided exceptional support, especially Varvara Ivanovna Egorova and Anatolii Bakhtin at GAKO. Karin Goihl at the Berlin Program facilitated scholarly camaraderie and guided me through German bureaucracy. Conversations in three languages and on two continents with scholars of the region, including Yury Kostyashov, Markus Podehl, Bert Hoppe, Per Brodersen, Katja Grupp, Natalia Palamarchuk, Holt Meyer, and David Bridges ignited my passion for Kaliningrad and people who have lived there.

In the early stages of research and writing, Victoria Bonnell got me to think about the practices of everyday life, and John Connelly helped me think outside the German and Soviet microcosm. Stephen Brain, Christine Evans, Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Alice Goff, Faith Hillis, Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, Filippo Marsili, Martina Nguyen, Alina Polyakova, Ned Richardson-Little, Kevin Rothrock, Tehila Sasson, Erik Scott, James Skee, Victoria Smolkin, Jarrod Tanny, and Ned Walker encouraged me to think about pictures big and small. Peggy Anderson and Reggie Zelnik deserve special thanks for encouraging me to put Russia and Germany together in the first place.

Many people, including members of the working groups at Berkeley, the Free University of Berlin, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, USHMM, Georgetown University, Columbia University, the Harvard Davis Center, Brown University, and Boston College, helped refine the manuscript through conversation or by commenting on the written text in part or as a whole. Numerous colleagues provided valuable feedback, including Rachel Applebaum, Jadwiga Biskupska, Johanna Conterio, Bathsheba Demuth, Rhiannon Dowling, Steven Feldman, Anna Ivanova, Emil Kerenji, Nataliia Laas, Vojin Majstorovi, Terry Martin, Jrgen Matthus, Erina Megowan, Alexis Peri, Serhii Plokhii, Steven Sage, Yana Skorobogatova, and Alan Timberlake. At Boston College, I was inspired by conversations with Julian Bourg, Thomas Dodman, Robin Fleming, Penelope Ismay, Marilynn Johnson, Stacie Kent, Lynn Lyerly, Yajun Mo, Prasannan Parthasarathi, Devin Pendas, Virginia Reinburg, Sarah Ross, Sylvia Sellers-Garcia, Franziska Seraphim (whose relative once lived in Knigsberg), and Conevery Bolton Valencius (who got me thinking about bodies and places more broadly). Yuri Slezkine, a friend and mentor in matters of form and content, helped give shape to the first draft and polished the final one.

This book, despite its lingering flaws and omissions, has been much improved thanks to constructive feedback from Brandon Schechter and Michael David-Fox. Series editor, David Silbey, and outstanding editors at Cornell, Emily Andrew, Bethany Wasik, and Karen Laun, shepherded the manuscript from submission to publication. Andrei Nesterov navigated Russian archives to secure image permissions, Irina Burns made my prose shine, and Gregory T. Woolston produced beautiful maps.

For steadfast support and intellectual engagement, I could wish for no better a friend than Ryan Calder. Erika Hughes continues to inspire me with her wisdom, joy, and poignant understanding of all things sacred and profane. Diane Cordeiro would certainly never read a book like this, but she is perhaps the person who most greatly facilitated its completion. Finally, this book is for Srdjan Smaji, for companionship and long-suffering patience, for Charley, who never lost faith, and for Sonja, who was not there at the start but made it all worth it in the end.

Archival Abbreviations

| AA | Archiv des Auswrtigen Amtes, Berlin |

| AP-Olsztyn | Archiwum Pastwowe w Olsztynie, Olsztyn |

| BA-Berlin | Bundesarchiv-Berlin Lichterfelde, Berlin |

| BA-Freiburg | Bundesarchiv-Freiburg, Militr-Abteilung, Freiburg |

| BA-Ludwigsburg | Bundesarchiv-Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg |

| GAKO | Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Kaliningradskoi Oblasti, Kaliningrad |

| GANIKO | Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Noveishei Istorii Kaliningradskoi Oblasti, Kaliningrad |

| GARF | Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Rossiiskii Federatsii, Moscow |

| GStPK | Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preuischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin |

| HIA | The Hoover Institution Archives, Palo Alto |

| MVS | Tsentralnyi Muzei Vooruzhennykh Sil, Moscow |

| RGAKFD | Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Kinofotodokumentov, Krasnogorsk |

| RGASPI | Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Sotsialno-Politicheskoi Istorii, Moscow |

| RGVA | Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennyi Voennyi Arkhiv, Moscow |

| TsAMO | Tsentralnyi Arkhiv Ministerstva Oborony, Moscow |

| TsDAVOU | Tsentralnyi derzhavnyi arkhiv vyshchykh orhaniv vlady Ukrainy, Kyiv |

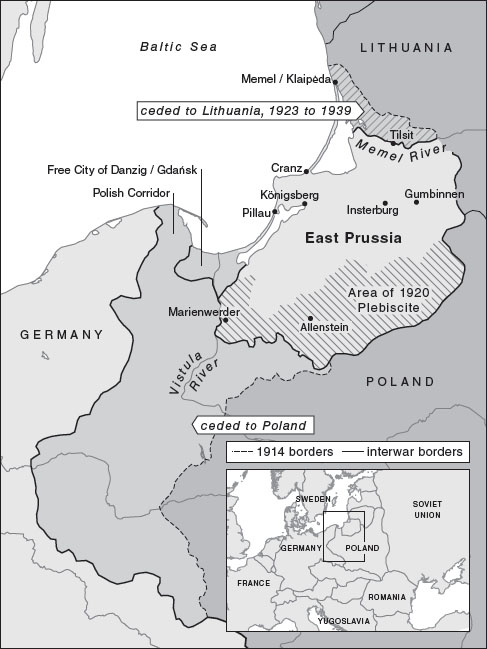

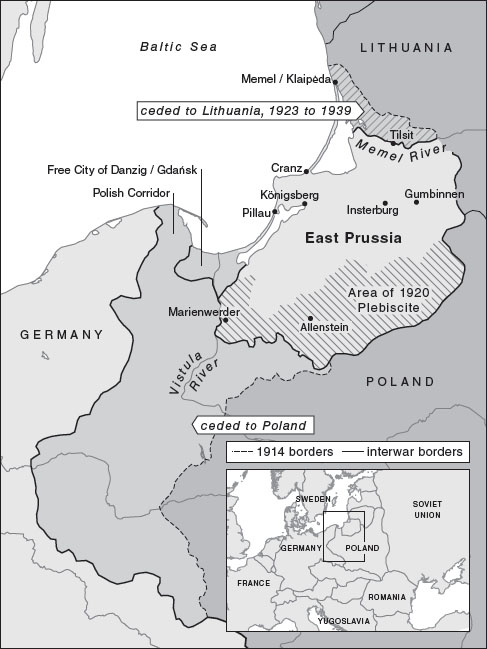

Map 1 . East Prussia in the interwar period.

Map 2 . East Prussia during the Second World War, showing annexed territories along the provinces borders and Reichskommissar Erich Kochs dominion in Ukraine.

Map 3 . Kaliningrad Oblast after the Second World War. The Memel/Klaipda region was granted to the Lithuanian SSR and the Masurian region to Poland. Kaliningrad Oblast became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1946.

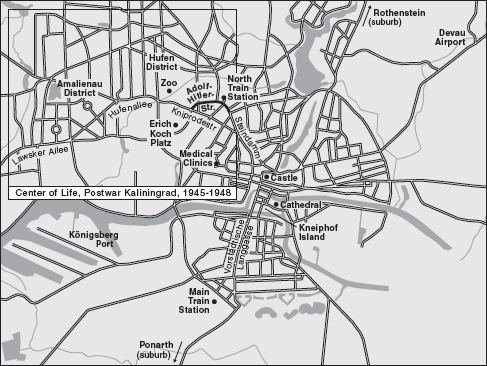

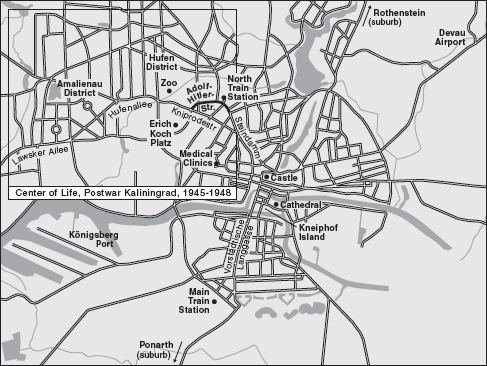

Map 4 . Map of Knigsberg, circa 1938. The wartime destruction of the historic city center led to the shift of postwar urban life in Kaliningrad to the turn-of-the-century suburbs northwest of the former city walls.

Introduction

Knigsberg/Kaliningrad is the only city to have been ruled by both Hitler and Stalin as their own domainnot only in wartime occupation, but also as an integral part of their empires. As a borderland of both the Third Reich and the Soviet Union, the city became a battleground of revolutionary politics, radical upheaval, and extended encounters between the two regimes and their more or less willing representatives. This book is about how Knigsberg became Kaliningradhow modern Europes two most violent revolutionary regimes battled over one city and the people who lived there. It offers a microcosm of the Nazi-Soviet conflict in the decade surrounding the Second World War. It explores how two states sought to refashion the same city and reveals how local inhabitants became proponents of radical transformation, perpetrators of exclusionary violence, beneficiaries of social advancement, and victims of oppression. The book focuses especially on the period from 1944 to 1948, when Germans and Soviets lived and died together, first under Nazi and then under Soviet rule, as they tried to make sense of the war that had drawn them together.

Next page

Map 1 . East Prussia in the interwar period.

Map 1 . East Prussia in the interwar period. Map 2 . East Prussia during the Second World War, showing annexed territories along the provinces borders and Reichskommissar Erich Kochs dominion in Ukraine.

Map 2 . East Prussia during the Second World War, showing annexed territories along the provinces borders and Reichskommissar Erich Kochs dominion in Ukraine. Map 3 . Kaliningrad Oblast after the Second World War. The Memel/Klaipda region was granted to the Lithuanian SSR and the Masurian region to Poland. Kaliningrad Oblast became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1946.

Map 3 . Kaliningrad Oblast after the Second World War. The Memel/Klaipda region was granted to the Lithuanian SSR and the Masurian region to Poland. Kaliningrad Oblast became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1946. Map 4 . Map of Knigsberg, circa 1938. The wartime destruction of the historic city center led to the shift of postwar urban life in Kaliningrad to the turn-of-the-century suburbs northwest of the former city walls.

Map 4 . Map of Knigsberg, circa 1938. The wartime destruction of the historic city center led to the shift of postwar urban life in Kaliningrad to the turn-of-the-century suburbs northwest of the former city walls.