John Willis - Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners

Here you can read online John Willis - Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Mensch Publishing, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

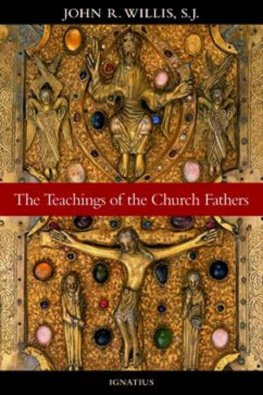

- Book:Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners

- Author:

- Publisher:Mensch Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Nagasaki

Nagasaki

The Forgotten Prisoners

John Willis

Mensch Publishing

51 Northchurch Road, London N1 4EE, United Kingdom

First published in Great Britain 2022

This electronic edition first published in 2022 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright John Willis, 2022

John Willis has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: HB: 978-1-912914-42-5; eBook: 978-1-912914-43-2

To Teddy, Rose, Lily, and Ida

Contents

In 1984, I was Head of Documentaries and Current Affairs at Yorkshire Television in Leeds and directed documentaries for our award-winning strand, First Tuesday. One of the most talented producers in the team was a Yorkshireman called Chris Bryer. One day Chris told me that his father Ron had been a prisoner of war (POW) in Nagasaki when the second atomic bomb was dropped. This was the most powerful bomb known to mankind and struck the industrial heart of the city, wiping thousands of its citizens off the face of the earth in an instant.

Although I had filmed in Hiroshima a few years earlier, this British connection to the atomic bomb was news to me. That August, Ron Bryer and his fellow former POW, Arthur Christie, had been invited back to Nagasaki as a gesture of reconciliation and peace. For us this was a unique opportunity to return to Nagasaki with Ron and Arthur, and to tell this extraordinary story to a wider public for the first time.

Ron Bryer had buried memories of his years as a Japanese POW deep inside. Back in Nagasaki images and sounds from his experiences inevitably resurfaced. Perhaps Ron needed to confront his wartime past so he could finally come to terms with more than three years of brutal imprisonment in the Far East? His return to Nagasaki was also a powerful and unforgettable experience for those of us who travelled with Ron, especially his wife Pat and son Chris.

In summer 2020 I published two books, Churchills Few and Secret Letters: A Battle of Britain Love Story, to mark the 80 th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. I am full of admiration for the remarkable courage displayed by the men who flew in defence of this country in 1940. Summer 2020 was also the 75 th anniversary of the Nagasaki bomb, and those two anniversaries became intertwined in my mind, and sparked thoughts about the nature of heroism. I compared the bravery of Battle of Britain pilots with the resilience of the prisoners who survived the many horrors the Japanese inflicted upon them.

My two 2020 books must have been well enough liked, because my publisher, Richard Charkin at Mensch, quickly asked me to write another book. I thought back to the story of Ron Bryer and the other POWs at Nagasaki; British, Australian, Dutch, and American. It was striking that even now the public knows almost nothing of their experiences. Apart from the building of the Thai-Burma Railway and the Bridge on the River Kwai, which have been portrayed in film, television, and literature many times, the rest of the Japanese POW experience is seriously underrepresented in the cultural mainstream.

The word that comes up regularly in all countries whose citizens were prisoners of the Japanese is forgotten the forgotten army, the forgotten squadron, the forgotten tragedy, the forgotten bomb, the forgotten war. Three years after that conflict ended, news agency APP-Reuters filed a story from Japan with a headline that captured the afterthought status of the second city to be destroyed, Hiroshima Famous, But for Nagasaki Oblivion.

In America the 25,000 prisoners of the Japanese have, says Australian academic Dr Rosalind Hearder, to all intents and purposes been obliterated from American public memory. Although they have become significantly more visible in recent years, Dr Hank Nelson noted that for several post-war decades in Australian history books, prisoners of war would just be mentioned in a sentence or part of a sentence no historian has written a book to cover the range of camps and experiences the prisoners have received no permanent place in Australian history. Their story is not immediately recalled on celebratory occasions.

The same can be said for the official war histories of the United Kingdom. In his excellent book on the River Kwai Railway, Sandhurst military historian Major General Clifford Kinvig pointed out that in the official five-volume The War Against Japan just ten pages are devoted to the experiences of thousands of British POWs. The 80 th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore on 15 February 2022 was marked in Singapore and Australia but was invisible in the United Kingdom. Yet, for the families of the POWs these men are certainly not forgotten. In recent decades, self-published accounts have mushroomed, often at the instigation of the children of those prisoners, eager to capture their fathers experiences before it was too late. Nor should we forget the vast numbers of Japanese civilians who died when bombs were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

I have chosen not to start this book with Nagasaki because by the time Ron Bryer, Arthur Christie and hundreds of others were imprisoned in that city, they had already been moulded by eighteen months of Japanese imprisonment. Before the bomb was dropped, they had already endured an extraordinary lottery of life and death which had changed their lives forever. For many, their first taste of war was in the steamy heat of Malaya, Singapore, or Java. Humiliating surrender in those places led to months of imprisonment before thousands were shipped off to build the infamous Thai-Burma Railway. If that was not harsh enough, POWs were then transported to Japan and elsewhere crammed into the holds of what were called hellships. By following their different rocky pathways through the dangers of conflict and capture, I hope that readers can better understand what shaped the behaviour and hopes of Nagasakis forgotten prisoners by the time the atomic bomb was dropped in August 1945.

Prisoners of Japan were spread throughout the Far East, in Borneo and Taiwan, in Ambon and Sumatra, in Hong Kong and Korea. The events in these countries were extraordinary and merit books dedicated solely to Allied captivity in those territories. I have chosen to focus on the under reported story of the prisoners in Nagasaki, and the experiences these men were subjected to before Fat Man , as the atomic bomb was called, was detonated close to their camps.

Contemporary accounts of life as a Japanese POW are rare. It was just too dangerous to keep a diary. Despite the risk, a handful of POWs did write down what happened to them. A diary was not only a way of remembering, but also gave prisoners a sense of purpose which helped them survive. It was a small, very personal, act of resistance. Discovery inevitably resulted in a nasty beating, or worse. It was no wonder that Dr Frank Murray, from Belfast, wrote riskier sections of his diary in Irish. Or that Australian Dr Rowley Richards buried a summary of his diary in the grave of a fellow POW.

Able Seaman Arthur Bancroft from Western Australia left his meticulous diary in the safe keeping of a mate in Singapore because he was worried that his prison transportation ship to Japan would be sunk, and the diary lost to the ocean. Bancroft was right to be cautious. His hellshipthe rusting bucket that carried him to the Japanese homelandwas holed by an American torpedo. On his return to Singapore, Arthur Bancroft found his diary safe but with several months of pages missing. The airmail-style thin paper had proved too tempting to his mates for rolling cigarettes.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners»

Look at similar books to Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nagasaki: The Forgotten Prisoners and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.