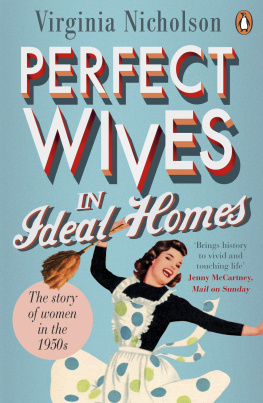

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2011

Published in Penguin Books 2012

Copyright Virginia Nicholson, 2011

The moral right of the author has been asserted

The Acknowledgements on constitute an extension of this copyright page

cover photograph (c) Mirrorpix.com

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-14-196974-9

By the same author

Among the Bohemians

Singled Out

For my mother, Anne Olivier Bell

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Virginia Nicholson was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and grew up in Yorkshire and Sussex. She studied at Cambridge University and lived abroad in France and ltaly, then worked as a documentary researcher for BBC Television. Her books include the acclaimed social history Among the Bohemians: Experinents in Living 19001939, and Singled Out: How Two Million Women Survived Without Men after the First World War, published by Penguin in 2002 and 2007. She is married to a writer, has three children and lives in Sussex.

Authors Note

In July 2005 the Queen unveiled a memorial in Whitehall dedicated to The Women of World War Two. This massive bronze structure, twenty-two feet high, is studded with a row of oddly spooky disembodied uniforms. Hanging from the monument are the clothes and belongings of the servicewomen, factory workers, farm-workers and women who worked in hospitals, emergency services and volunteer bodies across the nation between 1939 and 1945. They are suspended in a featureless void, with no faces, no personalities. In its way the monument is a perfect metaphor for our state of national amnesia. Six million-odd women threw their energies into the home front. 640,000 British servicewomen played their part in helping to win the war. Of these, 624 died for their country. But many of them are still alive.

Surely their endurance, their adventures, their sacrifices, their personalities are worthy of a deeper appreciation. This book asks, who were they? And what did it feel like to be them? I wanted to find out not only what they did in the war, but what the war did to them and how it changed their subsequent lives and relationships.

The chapters that follow are arranged chronologically, with the personal stories of a fifty-strong cast of characters in the spotlight against a backdrop of important social, political and international events: a momentous decade, seemingly familiar to many of us, but seen entirely through the eyes of the women who lived it. My approach to historical research is, as far as possible, to merge it with biography, and the telling of stories. I believe that the personal and idiosyncratic reveal more about the past than the generic and comprehensive. (A small note here: my intermittent but, I think, authentic use of the word girl to describe the young women of the 1940s may sound a little patronising today, but back then it was their own preferred term, and was also universally used in the press and literature.)

Among the many elderly women whom I interviewed and whose stories appear in these pages is my mother, Anne Popham, as she then was. Not because her experiences were unusual or heroic, but precisely because they werent. There have been numerous books celebrating the courage of women agents parachuted behind enemy lines in France, women in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, women pilots from the Air Transport Auxiliary who delivered Spitfires to their airfields. Odette Hallowes and Dame Margot Turner have earned their place in history alongside Douglas Bader and Stanley Hollis. My mother is now ninety-four years old. Like most of our mothers and grandmothers, and like the majority of women in this narrative, she grew up in a world that seemed small and sedate and did nothing starry or distinguished in the war. When it was declared in 1939 she was ordinary, frightened and unsuspecting. But six years of conflict reordered that world; along with an entire generation, she awoke to her own post-war potential. In all these respects she was entirely typical of the many millions for whose sake I have borrowed my title. (Millions Like Us was a propaganda movie made by Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat in 1943, to persuade women to join the war effort.)

If I could have chosen another title, it might have been We Just Got on with It the mantra of every woman I spoke to who lived through the war. So this book is not only an attempt to characterise that faceless war memorial, it is also my tribute to a generation of brave, stoical, unselfish, practical and uncomplaining women, whose values, along with their deeds, seem to be passing into history.

Prelude

A little over eighty years ago named Phyllis Noble was growing up in a terraced house with an outside toilet in Lewisham, south London. She was born in 1922. Her dad was a jobbing builder, and like many in the 1930s his trade was falling off; the Nobles financial situation was not improved by his fondness for the pub. Phylliss mum looked after the extended family of grandparents, in-laws and her own three children, who all lived under the same roof. As a role model Mum never overstepped the limits; she was first, foremost and exclusively a housewife, whose life revolved around the daily routine of shopping, cooking and washing. Despite the familys straitened circumstances Phyllis had a happy, rumbustious childhood. The kitchen in their cramped terrace house was a haven, and even when Dad had had a drop too much the family was united, roaring and joking when he let out one of his spectacularly loud farts. Phyllis was clever; but when she succeeded in winning a scholarship to a grammar school in Greenwich, Mum, disgusted at the expense of the uniform, launched a family battle to stop her daughter going. In any case getting educated would, in her view, be a pointless waste of time, since there was no alternative to the trap that she had herself been forced to enter twenty years earlier: that of marriage and motherhood.

To Phylliss relief Mum was overruled by Dad, and in 1933 she took her first apprehensive steps away from the crowded, working-class, patriarchal world of her childhood. A better accent and a better life beckoned, alongside dreams of romance and escape from her proletarian background. But by the time she was sixteen it was 1938. Dad sat gloomily at home reading the newspaper reports about mass unemployment and the threat of war.

In June 1939, aged seventeen, Phyllis Noble joined the ranks of the so-called business girls. She was to be a ledger clerk at the National Provincial Bank in Bishopsgate. Her workplace was a gloomy, noisy Victorian hall. Seated on a backless stool before her cumbersome ledger machine (a kind of monstrous typewriter), Phyllis was one of hundreds like her who spent their days sorting through piles of cheques, orders and statements to reconcile the banks accounts. Prospects for women in this world were virtually nil. Like their working-class counterparts, the maidservants in their basements and pantries, the business girls tended to be time-servers, dreaming of ensnaring their boss or male colleague into marriage. Then they could leave: