To Rob

Preface

On 8 November 2010, the British prime minister, David Cameron, led a substantial embassy to China. He was accompanied by four of his most senior ministers, and fifty or so high-ranking executives, all hoping to sign millions of pounds worth of business deals with China (for products ranging from whisky to jets, from pigs to sewage-stabilization services). To anyone familiar with the history of Sino-British relations, the enterprise would have brought back some unhappy memories. Britains first two trade-hungry missions to China (in 1793 and 1816) ended in conflict and frustration when their ambassadors proud Britons, both declined to prostrate themselves before the Qing emperor. These failures led indirectly to decades of intermittent wars between the two countries, as Britain abandoned negotiation and resorted instead to gunboat diplomacy to open Chinese markets to its goods chief among which was opium.

Despite happy snaps of David Cameron smiling and walking along the Great Wall in the company of schoolchildren, the 2010 visit was not without its difficulties. On 9 November, as Cameron and company arrived to attend their official welcoming ceremony at the Great Hall of the People at Tiananmen Square, a Chinese official allegedly asked them to remove their Remembrance Day poppies, on the grounds that the flowers evoked painful memories of the Opium War fought between Britain and China from 1839 to 1842.

Someone in Chinas official welcoming party had, it seemed, put considerable effort into feeling offended on behalf of his or her 1.3 billion countrymen (for one thing, Remembrance Day poppies are clearly modelled on field, not opium, poppies). Parts of the Chinese Internet which, since it came into existence some fifteen years ago, has been home to an oversensitive nationalism responded angrily. As rulers of the greatest empire in human history, remembered one netizen, the British were involved in, or set off, a great many immoral wars, such as the Opium Wars that we Chinese are so familiar with. Whose face is the English prime minister slapping, when he insists so loftily on wearing his poppy? asked one blogger. How did the English invade China? With opium. How did the English become rich and strong? Through opium.

In Britain, meanwhile, the incident was quickly spun to the credit of the countrys leadership: our steadfast ministers, it was reported, had refused to bow to the Chinese request. We informed them the poppies meant a great deal to us, said a member of the Prime Ministers party, and we would be wearing them all the same. (In recent years, Remembrance Day activities have become infected by political humbug, as right-wing rags lambast public figures caught without poppies in their lapels. In November 2009, the then-opposition leader, David Cameron, and the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, used the commemoration to engage in PR brinkmanship, both vying to be photographed laying wreaths for the war dead.) In certain quarters of the British press, the incident was read as an echo of the 1793 and 1816 stand-offs, with plucky little Britain again refusing to kowtow to the imperious demands of the Chinese giant.

Behind all this, however, reactions to the incident were more nuanced. For one thing, beneath the stirring British headlines of David Cameron rejects Chinese call to remove offensive poppies, it proved hard to substantiate who, exactly, in the Chinese government had objected. Beyond the occasional expression of outrage, as in the examples above, the Chinese cyber-sphere and press did not actually seem particularly bothered, with netizens and journalists calmly discussing the symbolic significance of British poppy-wearing, and even bemoaning the fact that China lacked similar commemorations of her war dead. The wider public response in Britain also appeared restrained. Reader comments on coverage of the incident in Britains normally jingoistic Daily Mail were capable of empathy and even touches of guilt. Just because [poppy-wearing] is important in Britain doesnt mean it means the same the world over. Im sure some of us in Britain are highly ignorant of the importance of Chinese history in China especially... the Opium War... no wonder they are a bit sensitive about it.

David Camerons poppy controversy was only the most recent example of the antagonisms, misunderstandings and distortions that the Opium War has generated over the past hundred and seventy years. Since it was fought, politicians, soldiers, missionaries, writers and drug smugglers inside and outside China have been retelling and reinterpreting the conflict to serve their own purposes. In China, it has been publicly demonized as the first emblematic act of Western aggression: as the beginning of a national struggle against a foreign conspiracy to humiliate the country with drugs and violence. In nations like Britain, meanwhile, the waging of the war transformed prevailing perceptions of the Middle Kingdom: China became, in Western eyes, an arrogant, fossilized empire cast beneficially into the modern world by gunboat diplomacy. The reality of the conflict a tragicomedy of overworked emperors, mendacious generals and pragmatic collaborators was far more chaotically interesting. This book is the story of the extraordinary war that has been haunting Sino-Western relations for almost two centuries.

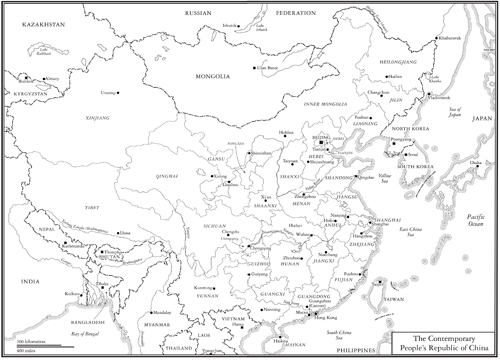

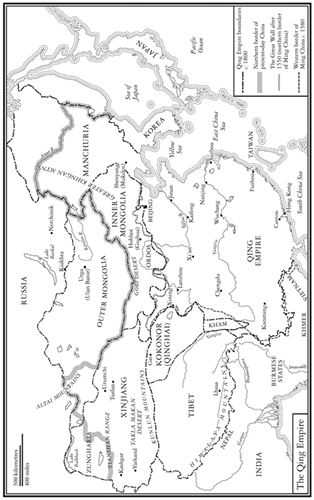

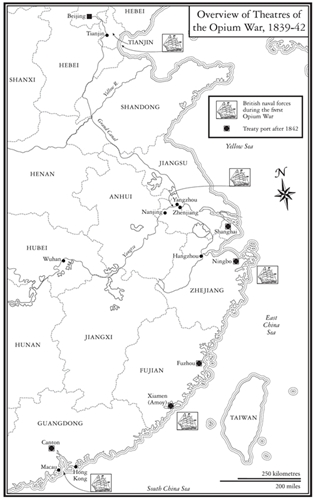

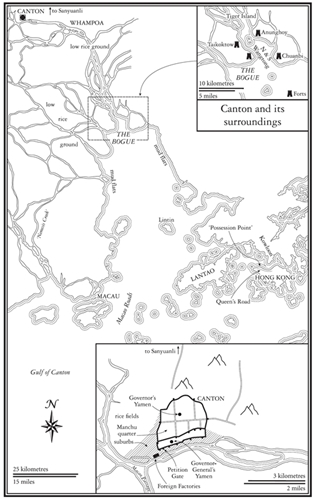

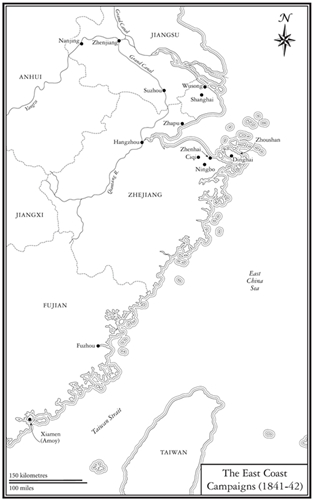

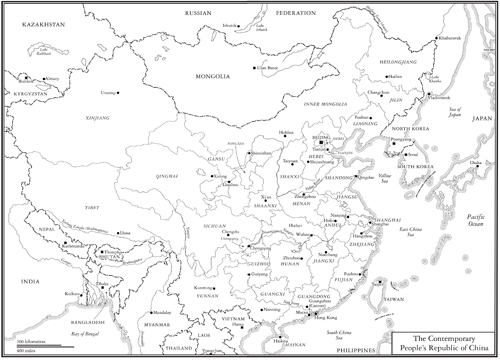

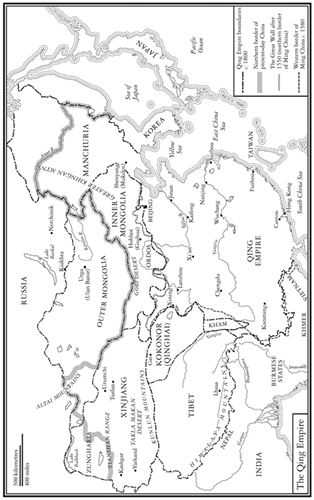

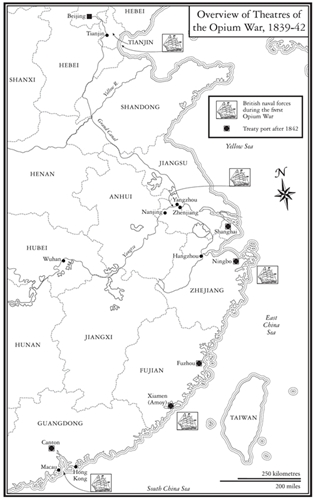

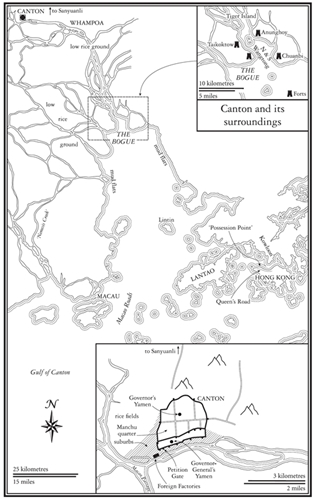

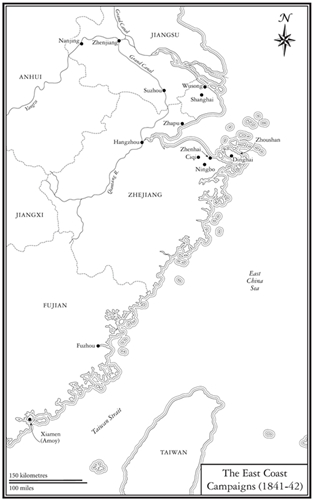

Maps

A Note About Chinese Names and Romanization

In Chinese names, the surname is given first, followed by the given name. Therefore, in the case of Liang Qichao, Liang is the surname and Qichao the given name.

I have used the pinyin system of romanization throughout, except for a few spellings best known outside China in another form, such as Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi in pinyin). In addition, I have occasionally used the old, nineteenth-century anglophone spellings of some Chinese place names (for example Canton, for the city known in Mandarin Chinese as Guangzhou) to reduce confusion resulting from more than one name being cited in the main text and in quotations from primary sources, and also because anglophone historians still call the pre-1839 rules governing European trade with China the Canton system.

In pinyin, transliterated Chinese is pronounced as in English, apart from the following sounds:

V OWELS

a (when the only letter following a consonant): a as in ah

ai: eye

ao: ow as in how

e: uh

ei: ay as in say

en: en as in happen

eng: ung as in sung

i (as the only letter following most consonants): e as in me

i (when following c, ch, s, sh, z, zh): er as in driver

ia: yah

ian: yen

ie: yeah

iu: yo as in yo-yo

o: o as in stork

ong: oong

ou: o as in so

u (when following most consonants):

Next page