About the Author

Giles Milton is a writer and historian. He is the bestselling author of Nathaniels Nutmeg , Big Chief Elizabeth , The Riddle and the Knight , White Gold , Samurai William , Paradise Lost and, most recently, Wolfram . His books have been translated into 18 languages. White Gold is currently being piloted as a major Channel 4 series.

He has also written two novels and three childrens books, two of them illustrated by his wife Alexandra.

He lives in South London.

www.gilesmilton.com

Acknowledgements

Much of the research material for Russian Roulette is housed in two depositories of archives: The India Office Records, now kept at the British Library, and the National Archives at Kew.

Special thanks are due to the ever-helpful staff of the India Office Records. They proved invaluable in guiding me through the 751 files of Indian Political Intelligence. They also provided access to Frederick Baileys photographic collection: two of his photographs are reproduced in the plate section of this book.

The staff of the National Archives proved helpful in locating key documents. The pictures of the M Device, also reproduced in the plate section, were found in one of the National Archives many files concerning the development of chemical weapons.

Thank you to the Institute of Historical Research.

The librarians of the London Library, where much of this book was written, have proved as helpful for Russian Roulette as they were for all my previous books.

A full list of sources is provided at the end of this book but special mention must be made of one author whose works have proved particularly inspiring. The doyen of Great Game specialists is Peter Hopkirk, whose books combine serious scholarship with page-turning narrative. Although new material has come to light in recent years, they remain a standard (and invaluable) reference for the subject of the struggle for control of Central Asia.

I am indebted to those spies who elected to publish their experiences, risking costly law suits for doing so. There is scarcely a page... that does not damage the foundation of secrecy upon which the Secret Service is built up. So reads a Secret Intelligence Service memo concerning the publication of Compton Mackenzies book Greek Memories , with its account of Mansfield Cumming.

First-hand accounts must be treated with caution: my aim throughout was to corroborate and balance the sometimes exuberant stories of the spies undercover adventures with the more sober tone of their intelligence reports.

Thank you to my literary agent, Georgia Garrett, for her hard work and ever-helpful advice; and to her team at Rogers, Coleridge and White.

Thank you, equally, to my editor, Lisa Highton, for her excellent advice, encouragement and supportiveness, and for seeing the project through from inception to publication.

Thanks are also due to Federico Andornino, Juliet Brightmore (for her work on the plate section) and Tara Gladden, who copy-edited the book.

I would like to single out my French editor, Vera Michalski, for special mention. She embraced the project from the outset and bought the French (and Polish) rights long before the book was completed.

Thank you, also, to the other foreign editors who will be publishing the book, notably Peter Ginna at Bloomsbury USA and Sindbad editors in Russia.

Lastly, a fanfare of thanks must be sounded for the home team: Alexandra, who read countless versions of the manuscript yet still managed to provide excellent (and much-needed) advice; and to Madeleine, Hlose and Aurlia for reminding me that there is life outside the world of espionage, skull-duggery and dirty tricks.

Magny, spring 2013.

Also by Giles Milton

Non-Fiction

The Riddle and the Knight

Nathaniels Nutmeg

Big Chief Elizabeth

Samurai William

White Gold

Paradise Lost

Wolfram

Fiction

Edward Trencoms Nose

According to Arnold

CHAPTER EIGHT

GOING UNDERGROUND

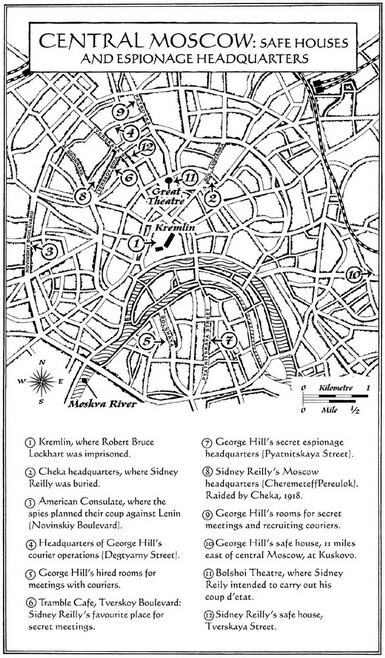

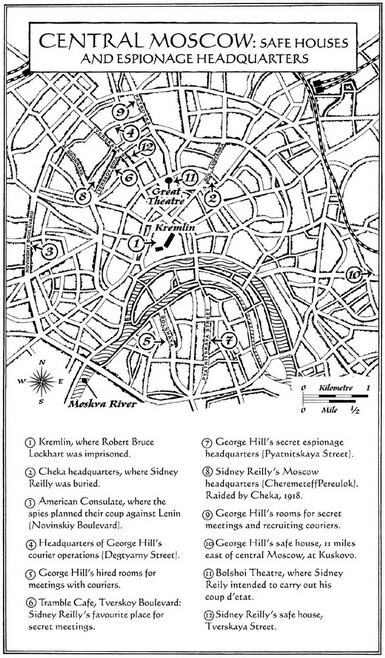

Sidney Reilly and George Hill found Moscow increasingly dangerous in the days that followed the landing of Allied forces in Northern Russia.

The Bolshevik leadership was incensed by what had taken place and was already calling it an invasion. In reality, it was not an invasion at all. A mere 1,500 men had been put ashore and their goal was to secure the stockpiles of unused weaponry, not to attack the Bolsheviks. Yet it had led to a swift reaction from Lenin and Trotsky. The raid on the Western consulates on the day of the landings was a clear sign that Bolshevik Russia was now a hostile power.

George Hill had been preparing to go underground for many months. Yet when the time finally came, he felt a sudden panic. I had a momentary but first-class attack of nerves, he wrote. In half an hour, I should be a spy outside the law with no redress if caught, just a summary trial and then up against a wall.

He took a few deep breaths to calm himself down. Then, after convincing himself that he was doing the right thing, he prepared to leave his flat and begin a wholly new life, taking a last glance at the treasured possessions he was leaving behind: My hat and sword, my photographs and favourite books, one or two prized decorations, various small things I had bought to take back to England...

He abandoned his Mauser and his Webley-Scott revolvers, reasoning that they would serve him no purpose. Nine times out of ten, a revolver is of no earthly use and will seldom get a man out of the tight corner. He much preferred his trusty swordstick, which he had wielded to deadly effect several months earlier.

The process of adopting his new identity was done in two stages. First, he left his apartment and went to a secure house that he had rented several months previously. I went out by a different entrance from the one I had used in entering, casually glanced round to see that I was not being followed, stepped into a cab and drove to the other end of Moscow.

Once arrived, he changed into a new set of clothes. These had been made to measure and delivered to the safe house some days earlier. There were three or four dark blue hessian shirts which buttoned at the neck, some linen underclothing, a pair of cheap ready made black trousers, peasant-made socks such as were on sale on the stalls in the market, a second-hand pair of top-boots and a peak cap which had already been well used.

Hill dressed hastily and then prepared to send his former identity up in smoke. I put my English suit, underclothing, tie, socks and boots into the stove; I laid a match to the kindling wood and shut the stove door. Ten minutes later, my London clothes were burnt.

His chief courier, Agent Z, arrived shortly afterwards with a new set of identity papers complete with stamps and visas for added authenticity. He also brought a cheap mackintosh, a hundred Russian cigarettes and the latest reports from various agents, which I put into the bag and then left the flat as George Bergmann. The switch of identities was complete: George Hill had ceased to exist.

He made his way to one of the poorer quarters of town, south of the Moscow River, to another of the flats he had rented. Here, he met up with his secretary, Evelyn, who was au courant with all the work I had been doing. Evelyn was partly English, but she had been educated in Russia and spoke both languages fluently, as well as German, French and Italian.

We had decided that our best chance of success was to become people of the lower middle class and to live an entirely double life. Evelyn had managed to get a job as a teacher in one of the new Bolshevik-run schools. This gave her the necessary papers and also the very coveted ration cards from the Bolshevik organisation; coveted because without cards or enormous sums of money, it was impossible to get food.

Next page