Introduction

It is often said that the First World War was an artillery war and that shell-fire caused over half of the battlefield casualties; Jonathan Bailey, for example, notes that shellfire and trench mortars together caused 58.51 per cent of Britains casualties in the Great War. Many of the tactical innovations during the war were in direct response to the impact of artillery on the battlefield usually inspired by the enemys own innovations, a process known as reciprocal development, where organisations develop and counter new technologies and organisational structures in a continuous competitive process. Yet the artillerys direct influence on both the planning and the conduct of operations has rarely been examined. There are numerous excellent books on guns, munitions and technology, many volumes dealing with individual battles that mention artillerys role in a specific operation, and a number of memoirs by artillerymen (which can sometimes come across as dry recitations of their most successful fire-plans). The best on artillery are those by Jonathan Bailey and Bruce Gudmundsson, but these deal with the wider evolution of artillery rather than specifically focusing on the events of the Great War. Perhaps many modern authors have been deterred from looking at the role of the artillery by the grim technical processes involved in industrialised, impersonalised killing and have therefore preferred to focus on the more human story of the infantry caught up in the terrifying environment created by the war in the trenches.

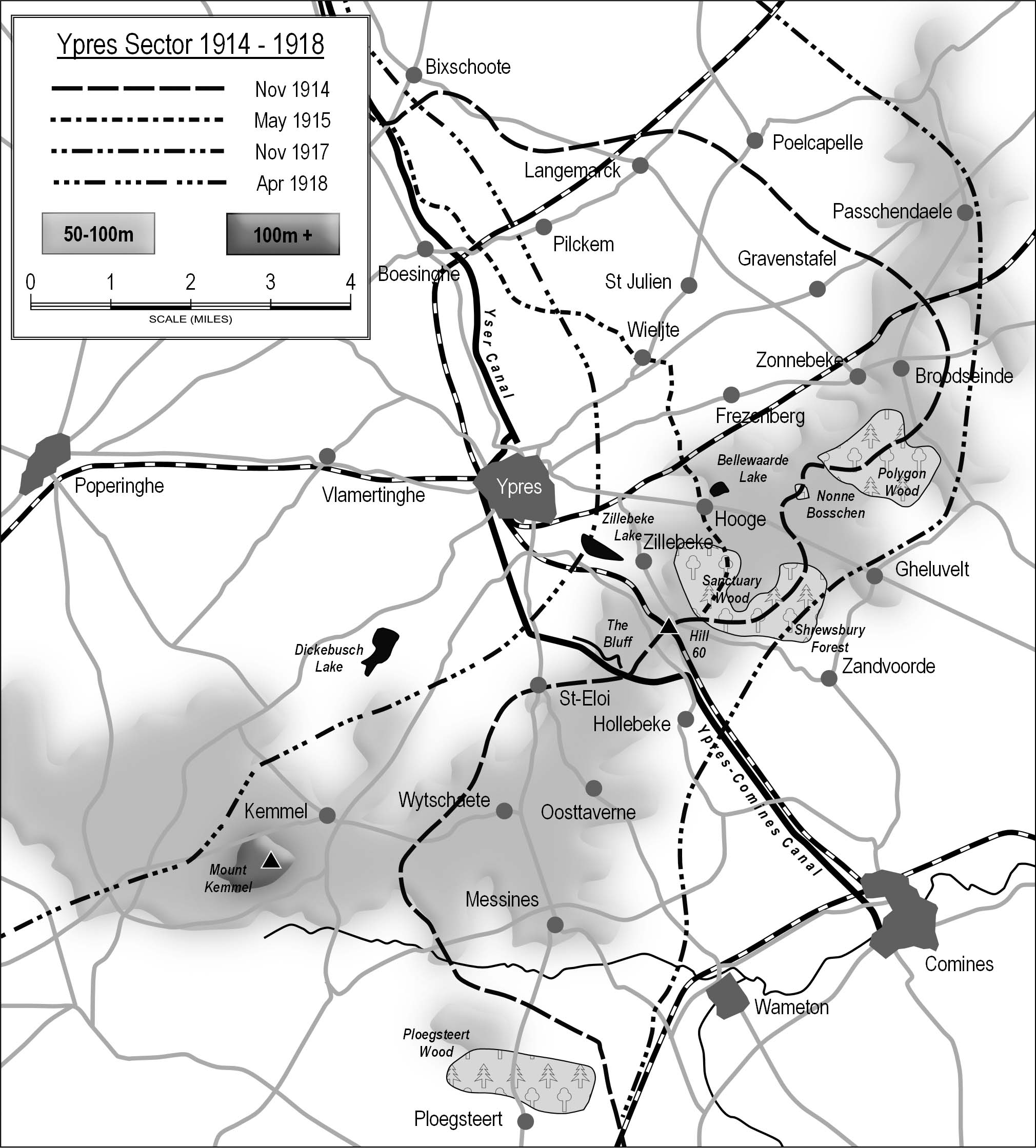

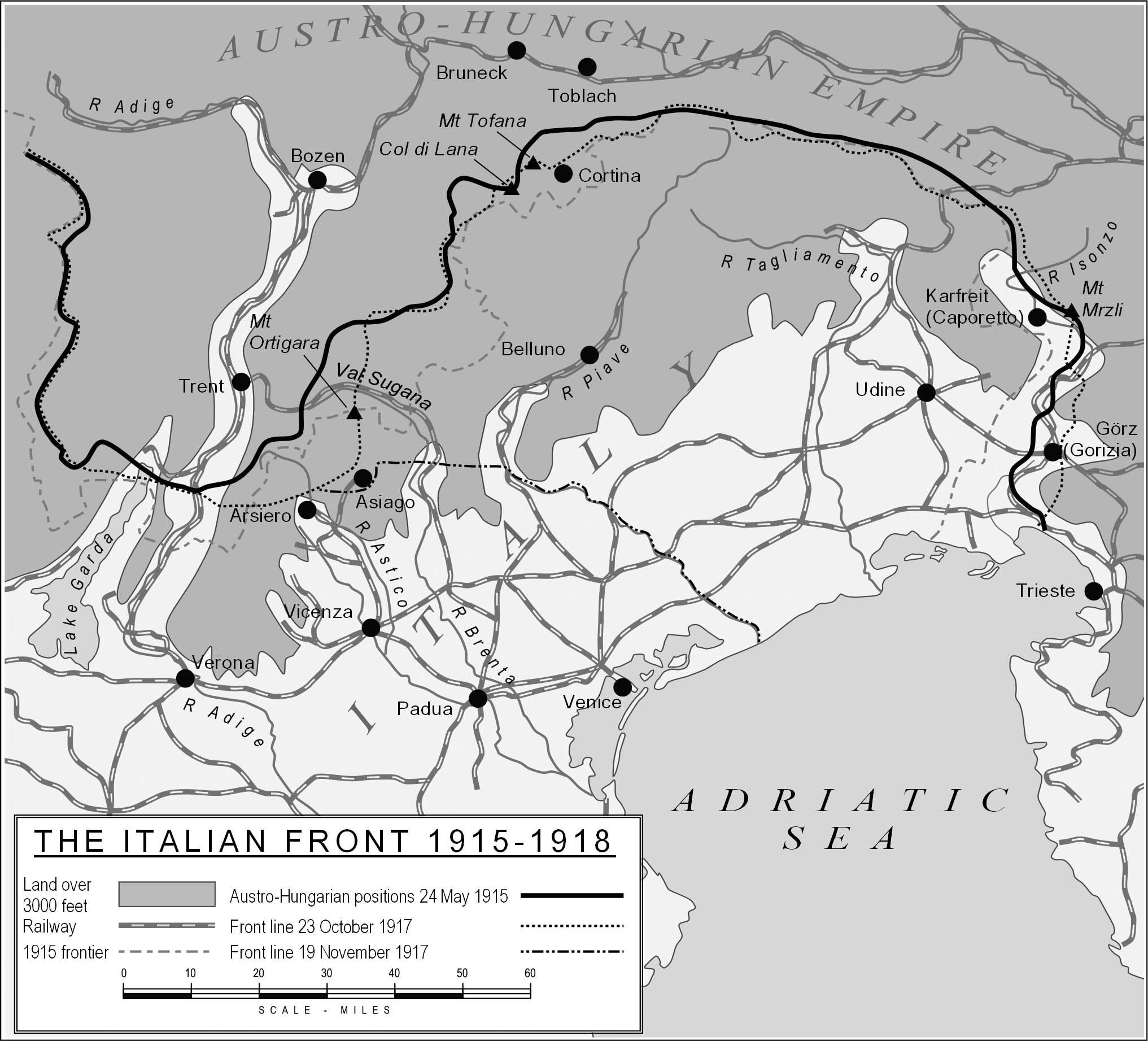

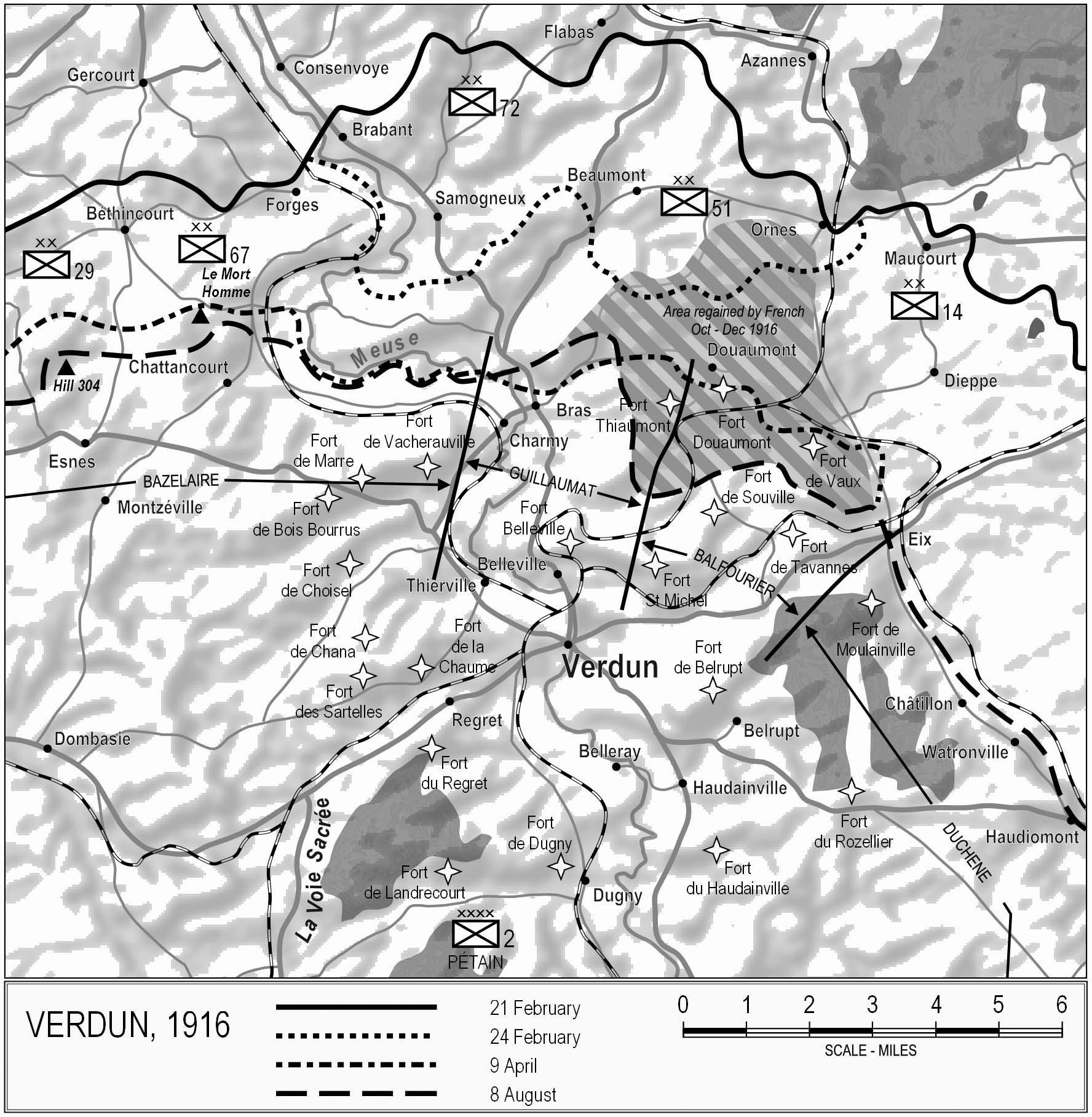

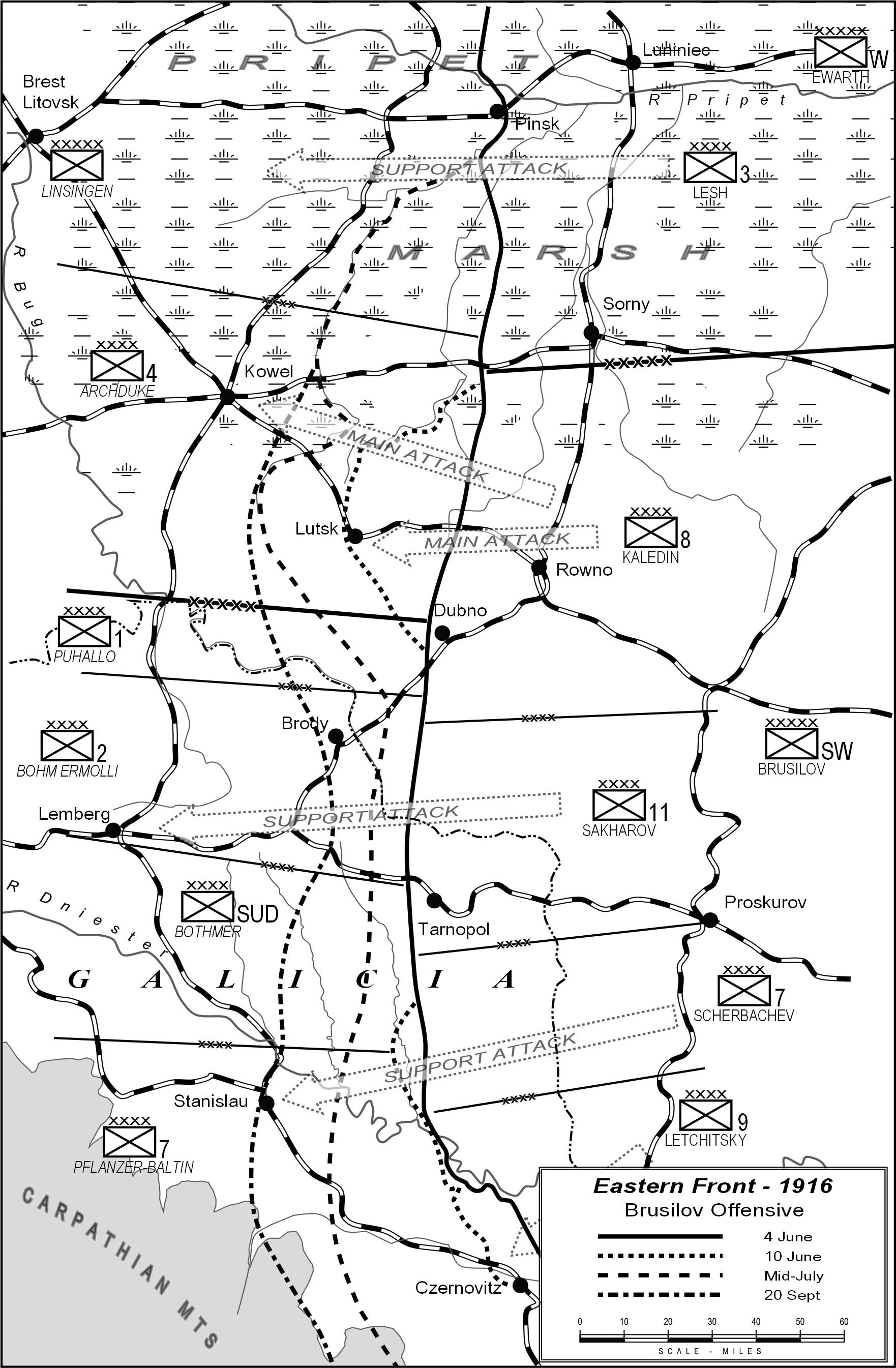

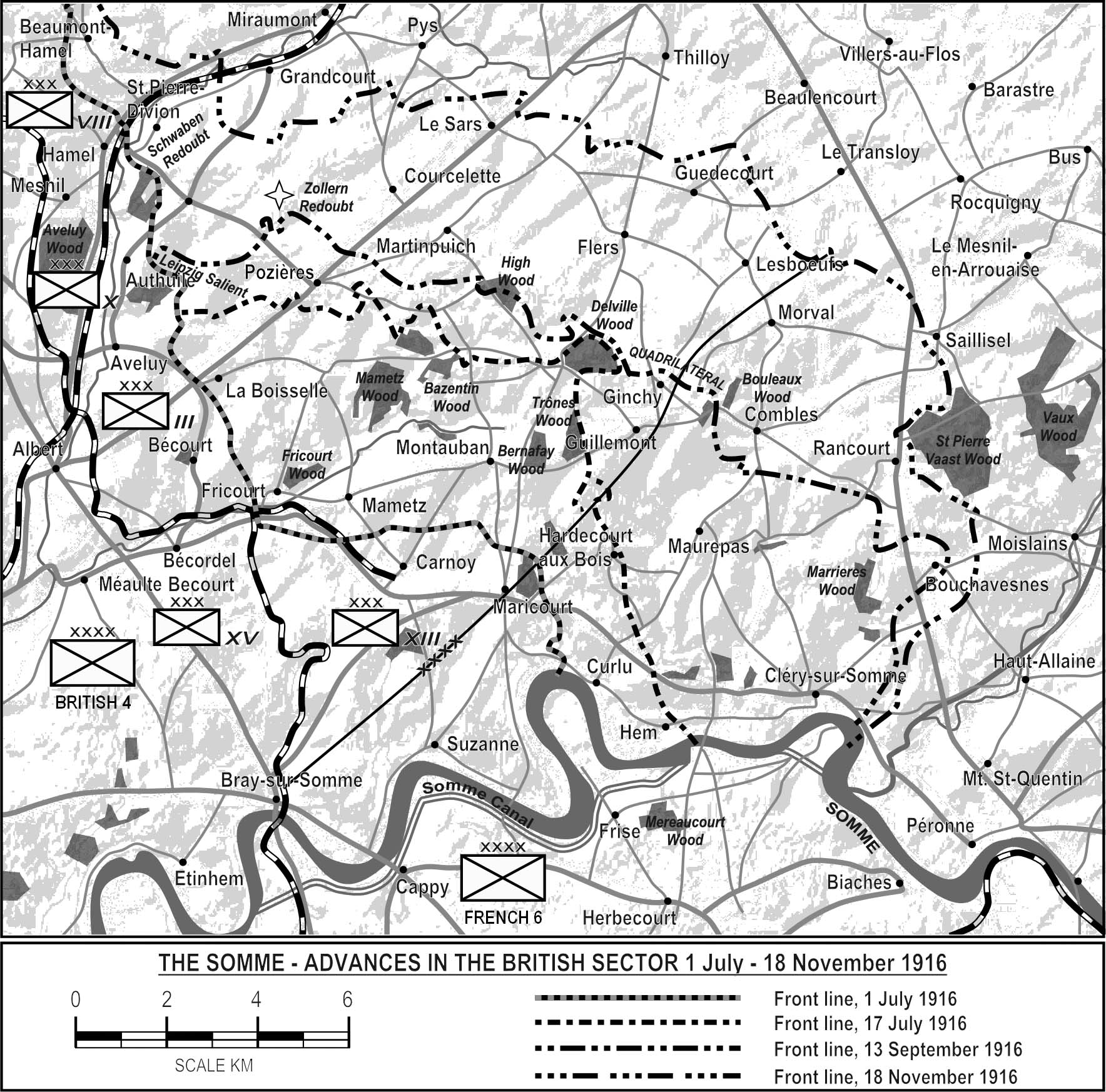

In this volume, we aim to start filling that gap. We examine each year of the war and look at key and representative battles on various fronts to explore how the constant process of reciprocal development affected both the conduct of operations and the people actually fighting the battles. We try to draw together the changing technologies of artillery and shells, and the innovations that affected accuracy such as mapping, sound-ranging and aerial observation. We also look at how military doctrine directly affected artillery and more generally at how artillery was fitted (or was not) into the evolving combined arms doctrine. We also examine how artillery was organised and commanded, because there were important differences that influenced its effectiveness. By looking at different countries and different theatres, we try to show how different armies faced varied circum stances and came up with unique solutions. Looking at a single nations military progress reveals only one learning curve associated with the particular circumstances in a given theatre, and thus inevitably fails to demonstrate the complex evolutionary processes at work. It would also fail to counter the assumption by some modern historians (and much of the popular media) that commanders in the First World War were less generally able than those who faced far less challenging circumstances in other wars.

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of those who read draft sections of the book, including John Lee, Tim Ratcliffe, Howard Body, Kathryn Walls and Patrick Rose, and those who kindly allowed us to quote from their work. We particularly want to thank Paul Evans and the staff of the Library of the Royal Artillery Museum who opened up the Aladdins cave of archival material in the Royal Artillerys remarkable collection, and Tim Ratcliffe who provided the superb maps and illustrations.

Given the enormity of the subject and the limited space available, faults and omissions inevitably remain and these are entirely our responsibility. We also want to thank Rupert Harding who allowed this project to go on longer than he wanted, yet helped us throughout! And to our families, who saw less of us as we worked on this, our thanks.

Prologue

The Battle of Le Cateau

After the thundershowers that covered II Corps retreat, Lieutenant General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien took the calculated risk to stand and fight on 26 August 1914 instead of continuing to withdraw. With four German corps plus cavalry marching forward, a gap opening on the right flank between II Corps and Sir Douglas Haigs I Corps, and only a weak French covering force on the left flank, II Corps faced a stiff fight as dawn broke. The encounter would go down in history as the battle of Le Cateau.

II Corps had three infantry divisions in the line, deployed along a ridge, and they would fight two different types of battle. The 5th Division, on the right, had an open flank, and Smith-Dorriens orders to stand and fight arrived late, so the troops had less time to select good positions and dig in. The 3rd Division (centre) and the 4th Division (left) had more time to pick their positions carefully and dug themselves in a bit with the rudimentary grubbers the men carried. With mist covering the ridge during the night, the men of the 5th Division ended up selecting positions that were on the forward slope when daylight came, they were able to see the enemy but their positions were visible to the enemy. This left the 5th Division in a weak position. The divisions artillery commander, Brigadier General John Headlam, compounded the problem. Following standard pre-war British practice, he decentralised his forces and attached a brigade of field guns (each brigade comprising three six-gun batteries) to each of the infantry brigades. Ordinarily, Headlam would still have the field howitzers (another three batteries) and the single heavy battery of 60-pounder long-range guns under his command, but he also split up the howitzer brigade, sending one battery to the 3rd Division and one battery forward, keeping only one battery, plus the heavy battery, as a reserve. Not only did the 5th Divisions artillery get split up, but it deployed far too far forward, in many cases amid the infantry.

In contrast, the 3rd and 4th Divisions deployed the bulk of their guns well behind the infantry and out of sight of the Germans. They would have to rely on signals (wig-wag flags, couriers or telephone messages) to know where and when to fire and they would have a harder time adjusting their fire or switching targets, but they were under cover and harder for the German artillery to hit. The trade-off was somewhat less firepower in exchange for better odds of survival, and surviving one day meant being able to provide firepower tomorrow. A few guns were deployed forward, up with the infantry, but staying silent until the advancing Germans were close enough to blast with shrapnel; some of these forward guns were disguised with corn stalks, since the crops had been cut but not gathered.