JENNIFER RATNER-ROSENHAGEN is the Merle Curti Associate Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin Madison.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2012 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2012.

Printed in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-70581-1 (cloth)

ISBN -10: 0-226-70581-1 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-70584-2 (e-book)

A subvention for this publication has been awarded through a competitive grant from the University of WisconsinMadison Provosts Office and the Graduate School. Graduate School funding has been provided by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) with income generated by patents filed through WARF by UWMadison faculty and staff.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ratner-Rosenhagen, Jennifer.

American Nietzsche : a history of an icon and his ideas/

Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-70581-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN -10: 0-226-70581-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Nietzsche,

Friedrich Wilhelm, 18441900. 2. Nietzsche, Friedrich

Wilhelm, 18441900Influence. 3. United States

CivilizationGerman influences. 4. Philosophy, American.

5. United StatesIntellectual life. I. Title.

B3317.R3382012

193dc22

2011011189

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

JENNIFER

RATNER-ROSENHAGEN

American

NIETZSCHE

A HISTORY OF AN

ICON AND HIS IDEAS

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

For My Parents

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PROLOGUE

Transatlantic Crossings

The Aboriginal Intellect Abroad

Truly speaking, it is not instruction, but provocation, that I can receive from another soul.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON , Divinity School Address (1838)

I profit from a philosopher only insofar as he can be an example.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE , Schopenhauer as Educator (1874), in Untimely Meditations

If book sales are a measure of literary achievement, Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche in 1881 was a positive failure. His first work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), caused quite a stir among a small circle of Wagnerians and philologists, but failed to catch the attention of the broader literary press and reading public. And yet this was his best-selling book during his lifetime; after that it was all downhill. The next year, David Strauss, the Confessor and the Writer (1873), the first of Nietzsches Untimely Meditations, received some initial attention but then quickly faded from view. The works that followed,Human, All Too Human (1878) and Daybreak (1881), went virtually unnoticed. Nietzsche never tired of contemplating the travails of the untimely genius. In a letter to a friend in August 1881, he bristled about an indifferent reading public, which let him starve on silence:

If I were unable to draw strength from myself, if I had to wait for applause, encouragement, consolation, where would I be? what would I be? There were certainly moments and whole periods in my life when a robust word of encouragement, a hand-clasp of agreement would have been the refreshment of refreshmentsand it was just then that everybody left me in the lurch.

But a few months later, as the protracted neglect exacerbated Nietzsches frustration, three admirers from Baltimore, Maryland, Elise Fincke, her husband, and a friend, sent him an epistolary lifeline:

Esteemed Herr Doctor, Perhaps it is of little concern to you that here in America three people often sit together and allow Nietzsches writings to edify them at their most intimate [aufs Innigste erbauen]but I dont see why we shouldnt at least tell you so once. We are counting on the fact that due to the depth of your thoughts and [your] sublime diction, we will never be able or want to read anything else ever again.

Nietzsches response to Fincke, both muted and arrogant, makes it difficult to appreciate how delighted he was to receive her praise. He informed her that he was now writing even more-challenging works, and that she and her companions should be duly forewarned: Who knows? who knows? perhaps you too wont be able to stand it and will come to say what some others have already said: He can run wherever he pleases and break his own neck when it pleases him too.

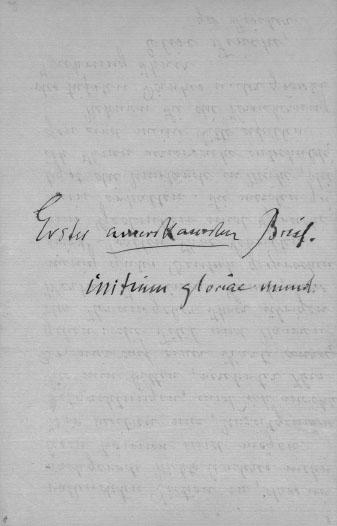

Such nonchalance, however, belied a deep sense of gratitude. His hand-written note to himselfwritten on the back of Finckes lettertells a different story. Clearly pleased, he marked the occasion: Erster amerikanischer Brief. initium gloriae mundi. Finally, it seemed, the world was waking to his genius.

In the ensuing months, however, silence settled back in. Nevertheless, Nietzsche found the inner resources to press ahead with his next book project. As he enjoyed a stretch of exuberant productivity, a second letter arrived from America, this time from a professional violinist named Gustav Dann-reuther living in Boston. He wrote to express, as he put it, my most humble thanks for the benefit I have derived from your works, and the wish (which I have long entertained) to possess a likeness, be it ever so small, of the man I have learned to adore for the greatness of his mind and the sincerity of his utterances. Dannreuther also took the opportunity to tell Nietzsche of his admiration for his Inopportune Reflections (Unzeitgemsse Betrachtungen ) and to inform him that he had translated his essay on Schopenhauer

no less than three times, not so much with a view to publishing my feeble reproduction, as to that of becoming more intimate with your work.

Nietzsches note to himself, written on the back of his first fan letter from the United States, 1881. Used by permission of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Goethe-und Schiller-Archiv, Weimar, Germany.

But in spite of my efforts, my version fell so far short of an adequate rendition of the original, that I was only too glad for the sake of your reputation to keep the manuscript in my desk. Since then I have quite destroyed it, but the memory of exalted moments remains, and I am sure that my work was at least not wasted upon myself.

We have no record of Nietzsches response. But one suspects that he might have figured that though the cultural philistines of Germany were unwilling or unable to recognize genius, in America, at least, there were people with ears to hear his untimely message. Two letters from America werent much, but given the paltry response to his writings at home, this surely seemed like an auspicious beginning. Could it be that the dawn of his philosophy was breaking in the West?

Nietzsche was barely informed about America. He made relatively few comments about it in his writings, and those that exist simply echo the commonplace enthusiasms and aversions of his day. Though Nietzsches America provided him with a symbolic field on which to imagine the curious formsthe new human flora and fauna, as he put ita modernized culture might produce, his characterizations are but conventional romantic stereotypes. If these romantic tropes were the only terms in which Nietzsche thought about America, it would be hard to imagine that the fan letters suggested to him that America might be a future home for his philosophy.

And yet this is not all Nietzsche imagined as he contemplated the New World. Indeed, when he thought about American intellect in particular, he thought about one specific American

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).