F OREWORD

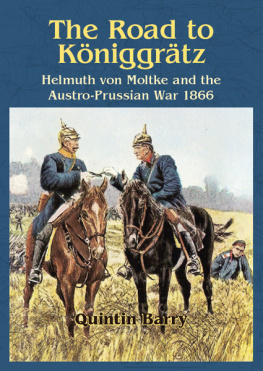

On June 2, 1866, King William I of Prussia directed that Gen. Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke, Prussia's chief of the General Staff, henceforth was authorized to issue orders directly to the operational commands. The royal order created a command relationship that effectively made Moltke the field commander of the Prussian armies assembled to fight Austria and its German allies. Although Moltke had held his position since 1857, he still was little known in the army. When several days later a Prussian divisional commander received an operations order signed Moltke, he is reported to have exclaimed, All this appears to be in good order. But who is this General von Moltke? His question would soon be answered.

Almost exactly one month later, on July 3, two Prussian armies, executing Moltke's bold and ambitious plan for what has come to be called a battle of annihilation, fixed the Austrian main army deployed in strength on the heights northeast of Kniggrtz with a series of frontal attacks. The battle remained undecided until just before noon, when a third Prussian army arrived to take the Austrian position in the right flank. With his position untenable, the Austrian commander ordered a withdrawal, which was orderly at first but turned into a near rout. Even so, arguably because his subordinate commanders were less willing than he to accept risks, Moltke's brilliantly conceived design fell short of perfection. The Austrian army was defeated but not annihilated. The bulk of it managed to escape, but for the time being it no longer constituted a cohesive fighting forcea fact recognized by the government in Vienna, which lost the will to continue the war and three days after the battle decided to seek peace terms.

Kniggrtz ended the struggle for hegemony in Germany and propelled Moltke into the front ranks of the great soldiers. When night fell over the battlefield no one asked any longer who General Moltke was. A campaign of only six weeks had ended with a decisive victory over the army of a major power, a power which at the outset of the war had been widely held to be superior to the Prussians. Moltke's reputation was further enhanced by the equally unexpected and rapid defeat of the Imperial French army in 1870.

These surprising results had been achieved by the application of Moltke's innovative theories. Most experts believe that the firepower of the new rifled weapons and the extended frontages occupied by ever-larger armies transported and supplied by railroads had made frontal attacks futile and flanking maneuver impossible. During the wars of 1859 and 1864, and in the American Civil War, these developments had created a near deadlock on the battlefield with a clear advantage for the defense, pointing toward future wars of attrition. But Prussia, a medium power with exposed frontiers, facing potential enemies on several fronts, could not afford to fight wars of attrition. It needed to achieve a rapid decision.

Moltke's solution, demonstrated in the campaigns of 1866 and 1870, was an adaption of the Napoleonic precepts of offensive war to the realities of the industrial age. His method combined rapid mobilization, transportation, deployment, movement, and combat into one continuous sequence, making every effort to bring superior numbers into the final decisive battle. With his forces initially deployed widely dispersed outside the tactical zone, Moltke intended to place the adversary between converging wings and then, with his own armies concentrating only on the day of battle, destroy him in a complete or at least partial envelopment, the Kesselschlacht.

To plan and execute this strategic sequence, Moltke enhanced the role of the Prussian staff officers and created the modern general staff system. No longer confined to administration and planning, this highly select and intensely professional elite was to participate with the commanders in coordinating the actions of the widely dispersed formations, an essential element in Moltke's strategic methods. In war, Moltke held, nothing was certain. No plan of operations, he wrote, survives the first collision with the main body of the enemy. Therefore, he concluded, strategyand in this context he included operations and even tacticswas little more than a system of expedients. Even so, the first, albeit all important, phases in the strategic sequencemobilization and transport schedules, and the initial deploymentcould be tightly controlled by good staff work on the expanding railroad and telegraph network. But once the armies were deployed, Moltke rarely issued more than a general outline of his plans. Army and major formation commanders were to act within the framework of general directives as opposed to precise orders, with their staff officers providing any necessary interpretation and guidance. Although criticized by some, this approach, a key component of Moltke's methods, provided the necessary flexibility to deal with different and unexpected situations, demonstrated by his use of external lines of operation in 1866 and internal lines in 1870.

Moltke also was prepared to shift his views on such fundamental issues as the question of whether war should be conducted offensively or defensively. Although he had taken the offensive in his wars, he always had favored the tactical defense when possible. After 1870, he became increasingly skeptical about the prospects of the strategic offensive. Looking at the geopolitical situationespecially the mounting threat of a two-front war and the continued improvement in weapons Moltke's first plan for war against France and Russia, prepared in 1871, warned that large-scale offensive operations could no longer rapidly produce a favorable decision. Instead, he favored a strategy of limited offensive-defensive operations, likely, he conceded, to end in a stalemate to be resolved by diplomacy.