A Guildhall Square in the early 1900s, before it was destroyed during the Second World War.

To Ian

A Desert Rat who survived the horrors of war,

never to speak of them.

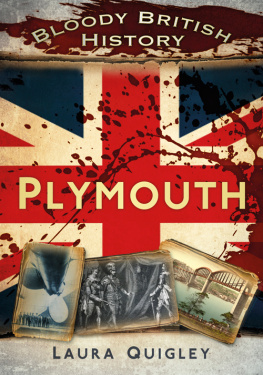

G ATHERING THESE STORIES has been a marvellous adventure. Plymouth has had more than its fair share of horrible history and it was a difficult task selecting just which ghastly and incredible stories to choose. Sadly, this also meant leaving out some of my favourites there was certainly enough for a second volume (hint to my editor there!). So this is by no means a complete history of Plymouth, and I recommend looking through the bibliography for some further terrific stories. All mistakes in re-telling these grisly tales are, of course, completely my own.

I include some individuals born in Plymouth who had grisly adventures elsewhere and I have used the modern Plymouth boundaries to define the area, incorporating the old towns of East Stonehouse, Dock (now known as Devonport), Stoke Damerel, Tamerton, Plympton and Plymstock, and also Cawsand. Although Cawsand is on the south west of Plymouth Sound and officially in Cornwall, to write about the customs officers of Plymouth and not mention their tormenting adversaries the Cawsand smugglers would be like writing about Normans and not mentioning the Saxons, so the rebellious free traders of Cawsand must also take their place in Plymouths history.

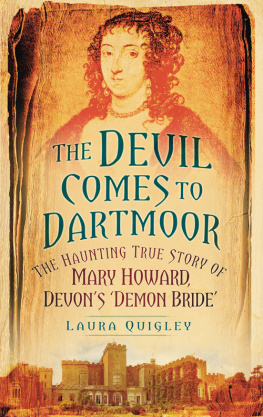

Huge thanks to everyone who read my first book, The Devil Comes to Dartmoor ; your support, encouragement and reviews were just wonderful. I am very grateful to my parents in particular, who seem to have bought copies for all of their friends! Thanks also to everyone at The History Press for their help, especially Cate, Declan, Ross and Ian who put up with all my emails. Marketing the first book while writing the second was quite a learning curve for me! Check out Facebook and www.lauraquigley.moonfruit.com for news and more images. I hope you find the following stories as darkly entertaining as I do.

Thanks also to the Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library, University of Toronto, for kind permission to use their images.

CONTENTS

8000 BC |

AD 650-700 |

AD 1348 |

AD 1296-1404 |

AD 1403-1588 |

AD 1580 |

AD 1579-1620 |

AD 1608 |

AD 1675 |

AD 1660-1822 |

AD 1768 |

AD 1797 |

AD 1799 |

AD 1815 |

AD 1830 |

AD 1831 |

AD 1700-1839 |

AD 1914-1918 |

AD 1939-1945 |

8,000 BC

P LYMOUTH WAS BORN at the end of the world. More than 10,000 years ago, there was no deep Plymouth harbour, and no English Channel. The Ice Age had drawn the seas away, leaving miles of tundra and grasslands in a vast river valley that divided the land masses we now think of as Britain and Europe. North Devon was under the ice. Rivers that would shape Plymouth harbour were then merely tributaries, digging out the cliffs as they flowed south into the fertile valley and joined the river into the Atlantic Ocean.

The valley was populated by nomadic hunter-gatherers, who moved north to hunt on the great tundra that was Dartmoor. They then returned south each year with the onset of winter. They made their homes on the freezing northern frontiers. These first Plymothians were a hard people: resilient, ferocious hunters. Once they had chased lions and hyenas in southern Britain, but now, with the coming of the Ice Age, they hunted mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, bears, wolves and reindeer. They travelled in canoes to trade their wares with Europe. One family made a home in the caves around Cattedown, with spectacular views of the English Channel valley.

Around 10,000 years ago, the Ice Age ended and the climate slowly changed. Sea levels rose again, steadily at first. A new sea formed the North Sea far to the north-east of Britain, its waters lapping against a natural dam formed by a series of ridges somewhere between Dover and Calais. The early hunters moved their settlements to new coastlines. With a warmer, wetter climate, the scrublands surrounding Britain became woodlands. The family at Cattedown now hunted smaller game amidst the forests of birch and pine, and gathered nuts, eggs and shellfish. They adapted, survived and thrived.

But they could not foresee the end of the world.

Around 5500 BC , the seas suddenly rose again. Some say Norwegian glacial lakes burst their banks and flooded south. The natural dam near Dover collapsed under the weight of water and the North Sea erupted into the valley below. A tsunami of unimaginable proportions engulfed southern Britain. The torrent destroyed everything in its path, flooding the valley and forming the English Channel. A forest at Bovisand, near Plymouth, drowned. The swirling maelstrom of water battered the steep hills, carving out a new coastline and forming estuaries around the rivers Plym and Tamar.

A vision of the prehistoric coastline. (Bart Hickman, SXC)

And so Plymouth was born, in the midst of devastation, eventually to become one of the most famous deep-water harbours in the world.

To the human population of the time, it was a catastrophe. Hundreds if not thousands died a whole society living in the English Channel valley drowned, their river settlements submerged and their remains swept away into the deep Atlantic Ocean.

What of the hunter-gatherer family who for so many generations had made their home in Cattedown? In 1886 a local journalist and antiquarian called R.N. Worth discovered caves in Cattedown, which is now a headland between the river Plym and the harbour. The caves contained the remains of fifteen Homo sapiens that were around 5,000 years old, along with the bones of hyenas, wolves, deer, mammoth and woolly rhinoceros which were up to 30,000 years old. Sadly these remains, once kept safely at the Athenaeum in Plymouth, were all but destroyed in another period of devastation for Plymouth the Blitz of the Second World War though the few charred pieces that survived are now on display at the Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery at North Hill. It is astonishing to imagine what the remaining skull there in its glass case in the museum must be thinking to have survived millennia, an Ice Age and a deluge, only to be bombed by the Germans.

No one will ever be certain what actually happened to these fifteen people in Cattedown. Perhaps they were drowned as they slept. Perhaps they survived the deluge, living on the high ground, and were buried in their time on the shores of the old world. For many years after the deluge, ancient man would ride out into the Channel in small boats to drop tributes into the water a memorial to their ancestors and an old world they would never see again.

As the few survivors stood on the new coastline, they knew their world had ended. Gazing out over a vast new sea, they realised that to trade or even to communicate with the rest of the known world, they were going to need bigger boats.

Next page