Paris! Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated! Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France, of the France that fights, of the only France, of the real France, of the eternal France!

Foreword

Maurice Vasse

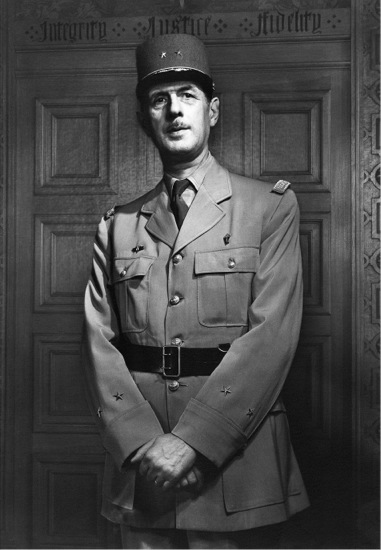

W riting a book about a historic figure, or a period in history, is somewhat like painting a portrait or a landscape. No two people will produce a work that looks exactly the same; we all project a little bit of ourselves into the work. The appeal of The Paris Game stems from the fact that its author reveals he is a lover of Paris and an admirer of Charles de Gaulle, and one can read these sentiments in every line. Every biographer of the Man of the 18th of June has chosen to emphasize a particular aspect of his character, and this is also the case for Ray Argyle.

I would first like to say why it was a pleasure to read him. He is an author who innovates and surprises, often resorting to lesser-known Canadian and American sources, alongside the better-known French documentation, such as Charles de Gaulles own Mmoires de guerre . The detailed Notes and Sources that Argyle has included are particularly useful, revealing his knowledge of the culture and the life of France.

Although the book is well-documented, it pleases me especially because to read it is to enjoy a refreshing change from academic histories. It is not cluttered with abstract references and considerations. Instead, it is distinguished by its practical approach and the liveliness of its depiction of the personalities. The author likes to portray people and things in their environment and in their everyday life; they are not mere abstract figures or intellectual entities. De Gaulle has a family, wife, children, and Argyle excels in giving them their proper place in the family environment.

The book places great importance on a variety of interesting figures, each of whom had a role in the liberation and recovery of France. They include such personalities as Jean Moulin, Elisabeth de Miribel, Philippe Leclerc, and de Gaulles son, Philippe, along with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Less attention is paid to ministers, administrators, diplomats, and military figures those that may be referred to as de Gaulles entourage. Because we forget too often, it is worth remembering, as does the author, that de Gaulle did not transform France alone. He was aided by members of a supportive circle that extended from London to Algiers, and from de Gaulles home in Colombey-les-Deux-glises to the presidential suite at the lyse Palace.

But men and women are not the only ones to play a role in this book. There is also the immortal Paris, which holds a place of prime importance. Paris is not merely the setting for the events described so well by the author, but a real actor in the story and the main stage on which General de Gaulle performed. As a lover and a connoisseur of the capitals different neighbourhoods, the author describes the principal scenes in which Charles de Gaulle acted out his career. This is a book full of interesting portraits and little-known facts that hook the reader with a sense of action and life.

To paraphrase Pirandello, who wrote, To each his own truth, I could say, To each his own de Gaulle. Argyle has made his choice: he has chosen to put the Man of the 18th of June on the stage the man who rallied the French to fight on. For my part, I would have appreciated it if Argyle had described the following years of de Gaulles career with the same precision he has applied to that era. But there you have it; it is his choice, which he illustrates by focusing on the period of the Second World War and the French Resistance (19391945), rather than on the presidency of General de Gaulle (19581969). In this sense, Argyle is in agreement with a majority of the French, for whom Charles de Gaulle remains the Man of the 18th of June and the man of legend.

Readers of The Paris Game will not find lengthy arguments on issues that continue to divide analysts: Was de Gaulle a republican or was he a Bonapartist a man for the people or a would-be emperor? Was he a doctrinarian or was he a pragmatist? And if he was a doctrinarian, what was his doctrine? Was he a man attached to the nation-state, and as such, unable to understand the postwar world? Or was he a true European? Was he anti-American in the 1960s in reaction to his wartime experiences? Or was he merely enamoured of national independence and conscious of Frances need to remain close to the United States? Was de Gaulle determined to preserve Frances domination of its colonies and was his approach to decolonization thus a sham? Or did de Gaulle understand the new path that was opening up for France: the path to progress through co-operation? And what did the Gaullian call for the greatness of France really signify?