For Mary, finally

It happened to happen. All at the same time. Every day was a party. It was like a child who has been under the parents control, and all of a sudden on the eighteenth birthday, they say, Here is the key to your Ferrari, here is the key to your house, here is your bank account, and now you can do whatever you like. It was enough to go mad! The new century started in 1960. After that, its only been perfecting what we started.

Alvaro Maccioni, restaurateur

Grey.

The air, the buildings, the clothing, the faces, the mood.

Britain in the mid-1950s was everything it had been for decades, even centuries: world power; sire of glorious intellectual, aesthetic and political traditions, gritty vanquisher of the Nazis, civilising docent to whippersnapper America, bastion of decency, decorum and the done thing.

But somehow, in sum, it was less.

Its colonies were demanding freedom and getting it; such unilateral forays into geopolitics as Suez were fiascos; its cuisine, architecture, popular entertainment, fashion and cinema succeeded only when mimicking continental or American models, as Matt Munro, Lonnie Donegan, Diana Dors and Norman Hartnell had done; it stood stubbornly outside a centralising Europe while shrinking alongside the US as standard bearer of Western values in a crystallising Cold War; it was a noncompetitor in the arms race, the space race and, more and more, the prestige race. Winston Churchill, hero of decades ago, sat in Parliament, and the spoor of antique manners lay thick in the air; it seemed a nation not so much in decline as left behind.

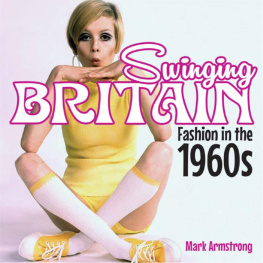

The States, France, Italy all felt modern. Rock music and the rise of the teenager as tastemaker made the American scene come on, naturally, loudest, while decadent, savvy, grown-up style made existential Paris and La Dolce Vita Rome meccas for both the international jet set and an emerging global bohemian underground. England by contrast was dowdy, rigid and, above all, unrelentingly grey, grey to its core.

In 53 fully eight years after the war had ended Britons were still eating rationed food, answering natures call in backyard privies, and making their daily way through cities that bore the deep scars of Luftwaffe bombing. Germany, Italy and Japan the losers, mind you were seeing their economies revitalise; France, which had been ravaged, was in recovery. But in Britain, the hard days still seemed alive. For many Britons, the mid-1950s were materially and psychologically a lot like the mid-1950s. It was, in the words of critic Kenneth Tynan, a perpetual Dunkirk of the spirit, made more bitter, perhaps, with the false glimpse of spring that was a young queens coronation.

Within a few years, however, that was to change. By 1956, the British economy had finally relaunched itself: key industries were denationalised by a conservative government; American multinationals were choosing Britain as the home base for their expansion into Europe; unemployment dipped, spiking the housing, automobile and durable goods markets; credit restrictions were eased, encouraging a boom in consumerism; and the value of property particularly bombed-out inner-city sites soared. In just three years, the English stock market more than doubled in value, and the pound rose sharply in currency markets.

Inevitably, as in America, prosperity led to complacency and nostalgia for a pre-war era that only in retrospect seemed golden. The mood, taken at large, was smugor would have been, if smugness had been considered good form. The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, patting himself on the back in 1957, declared Youve never had it so good. And in many respects he was rightif you were of certain tastes and strains of breeding.

The common conception of big city excitement women in long skirts, men in dinner jackets, dance band music, French cuisine, a Nol Coward play and a chauffeured Rolls was just as it might have been in the 1920s. London was kind of a grown-up town, remembered journalist Peter Evans. It was an old mans town. Nightclubs were where you went if you wanted to hear people playing the violin. There was nowhere to go. Even Soho closed early. There were drinking clubs, but they were private. There was nothing for young people, remembered fashion designer Mary Quant, and no place to go and no sort of excitement.

But as, again, in America, there were intimations of a burgeoning dissatisfaction with the status quo. And, perhaps because it had been beaten down for so long, or perhaps because its increasing marginalisation on the world stage liberated it from grave responsibilities, Britain seemed particularly fertile ground for this sort of seed.

At a pace that seemed wholly un-British, various strains of unofficial culture defiant, anti-authoritarian, and hostile to such commonplaces of tradition as modesty, reserve, civility and politesse were coalescing, not so much in unison as in parallel. Bohemians in Chelsea and Soho; radical leftists from the universities and in the media; teens with spending money, freedom and tastes of their own; these three groups would evolve and meld over the next few years to bring forth a dynamic that would centre in London and become a global standard. You could point to a few shops, pubs, coffee bars, theatres and dance halls where it all started; you could walk to all of them in a single fair day; and you would, in so doing, encompass an entire new world.

Ten years, maybe fifteen, maybe six.

London rose from a prim and fusty capital to the fashionable centre of the modern world and then retreated.

The 50s were Paris and Rome.

The 70s, California, Miami and New York.

But the 60s, that was Swinging London the place where our modern world began.

Hardly any of the elements were unique: there had been bohemian revolutions and economic renaissances and new waves in the arts and popular culture and lifestyle before. There had even been other moments when youth dominated the scene: the Jazz Age of the 20s, the brief rock n roll heyday of the 50s.

But in London for those few evanescent years it all came together: youth, pop music, fashion, celebrity, satire, crime, fine art, sexuality, scandal, theatre, cinema, drugs, media the whole mad modern stew.

Decades later, the blend that was Swinging London has come to seem organic: whole empires would rise and fall on the mix, the bread and circuses and lifeblood of the contemporary mind; no one could imagine life without it or remember when things were different. Yet prior to the day when London hit full swing some time, more or less, in August 63 it hadnt existed. Within three miles of Buckingham Palace in a few incredible years, we were all of us born.

It wasnt youth culture that England invented from James Dean to Levis to Elvis, that was America through and through but where American official culture at the end of the 50s had effectively tamped down the expressive impulses of young people, England had embraced them as a way of emerging from decades, maybe centuries, of slumber. It let them grow, coalesce, strut. London was where youth culture finally cemented its hold on all forms of expression, and made itself loudly and exuberantly known. Youth, once something to endure, transformed in the span of a few years of British sensations into a valuable form of currency, the font of taste and fashion, the only age, seemingly, that mattered.

The Brits who created Swinging London were unique in their resilience, their ability to absorb and transform elements of American and continental culture, and the cocksureness with which they flaunted their invention of themselves. Quite a tough bunch of kids made it through the war, reflected tailor Doug Hayward. And their toughness was one of their chief assets in their attack on tradition, as Barbara Hulanicki, who outfitted so many of the hip young girls at her Biba boutique, concurred: The postwar babies had been deprived of nourishing protein in childhood and grew up into beautiful skinny people. A designers dream. It didnt take much for them to look outstanding.

Next page