Stephen Harding

THE LAST BATTLE

When U.S. And German Soldiers Joined Forces in the Waning Hours of World War II in Europe

As always, for Mari, with love

ON THE MORNING OF MAY 4, 1945, Captain John C. Jack Lee Jr. sat cross-legged atop the turret of his M4 Sherman tank, comparing the narrow streets before him with the terrain features marked on the map that lay partially open across his lap. Lee, a stocky twenty-seven-year-old from Norwich, New York, had spent the last five months leading Company B of the 23rd Tank Battalionand, at times, much of the entire U.S. 12th Armored Divisionon a headlong advance across France, into Germany, and now, in what would turn out to be the last days of World War II in Europe, into the Austrian Tyrol.

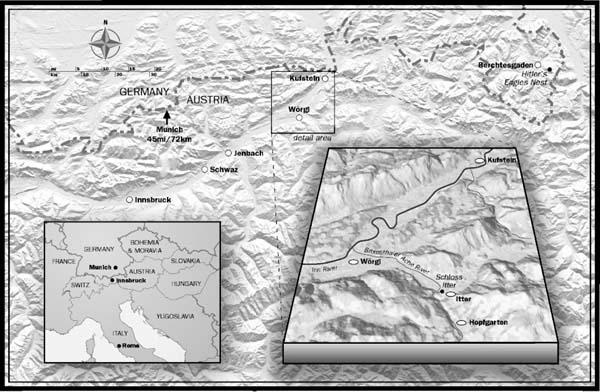

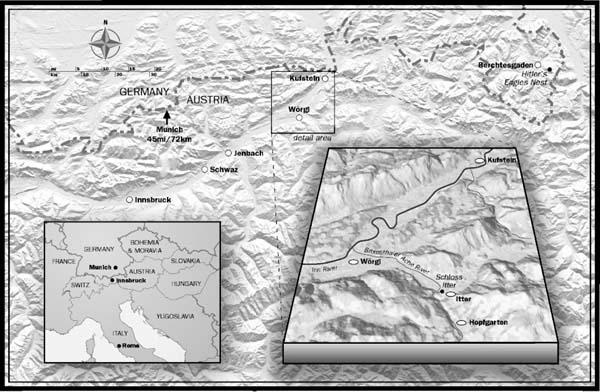

Lees tank was parked at the intersection of two streets in the town of Kufstein, Austria, three miles southwest of the German border on the south bank of the swift-flowing Inn River. All three of the 23rds tank companies had crossed the frontier the day before, leading the 12th Armored Divisions Combat Command R on its drive southward from the suburbs of Munich. Lees company had spearheaded the drive into Kufstein and had fought its way through a well-defended German roadblock before quickly clearing the town of its few defenders. Now, with the situation stabilized and lead elements of the 36th Infantry Division moving in to assume responsibility for the area, Lee and his men could catch a few minutes rest.

JUST A FEW MILES TO THE SOUTHWEST another tired officer was also scanning a map, trying to determine what the coming hours would hold for him and his men. Josef Sepp Gangl, a decorated Bavarian-born major in the German Wehrmacht, knew that the American juggernaut was rolling his way and that its arrival would likely be heralded by thunderous artillery barrages, the roar of tank fire, and the rattle of automatic weapons.

Gangl was not unduly troubled by the possibility of his own death; hed come to grips with his own mortality fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front and the Allies in Normandy. He was concerned about the men he led, however, for not all were soldiers, and many werent even German. A few days earlier, knowing the war was lost and loath to spend any more lives defending a system hed long before stopped believing in, Gangl had declared his own personal armistice and joined forces with the Austrian anti-Nazi resistance. His only goal now was to keep the advancing Americansand, for that matter, any German units still loyal to the fhrer and the Reichfrom butchering the men whod chosen to follow him.

ATOP A ROCKY PROMONTORY overlooking the flatlands over which the Americans would soon advance, a gaggle of argumentative Frenchmen were also pondering what fate had in store for them. Peering over the battlements of a castle that had stood atop its mountain for centuries, and that had been their prison until that very morning, the men knew their newfound freedom was no protection against the wrath of die-hard SS units still roaming the thick forest around them. They needed deliverance, and they needed it soon. If help did not come before the sun set, they would almost certainly die within the walls of their Tyrolean fortress.

THE WARMTH OF THE SPRING SUN and Jack Lees exhaustion made it difficult for him to focus on the map. He was profoundly tired and hoped, more fervently than he let on to his men, that Kufstein would be Company Bs last battle. Like virtually every other soldier in the European theater of operations, Lee knew that the war could end at any momentAdolf Hitler had killed himself five days earlier, and organized German opposition was crumblingand, while the young officer would in some ways hate to see the conflict come to a close, he didnt want any of his men to be the last American killed in Europe.

As Lee pondered what the wars end would mean to him and his fellow tankers, events were unfolding literally just down the road that would shatter his mens dreams of peace. Though he didnt yet know it, Lee was about to be thrust into an unlikely battle involving the alpine castle whose icon was obscured by a fold in his map, a group of combative French VIPs, an uneasy alliance with the enemy, a fight to the death against overwhelming odds, and the lastand arguably the strangestground combat action of World War II in Europe.

CHAPTER 1

A MOUNTAIN STRONGHOLD

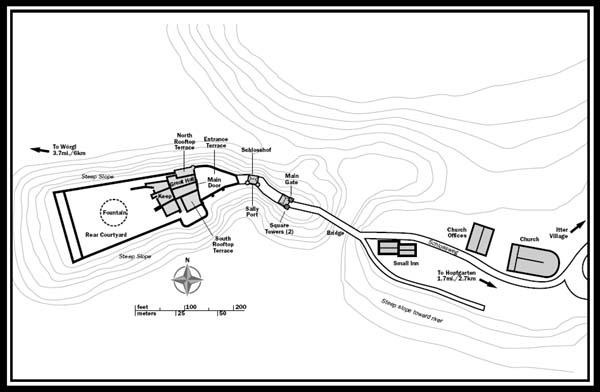

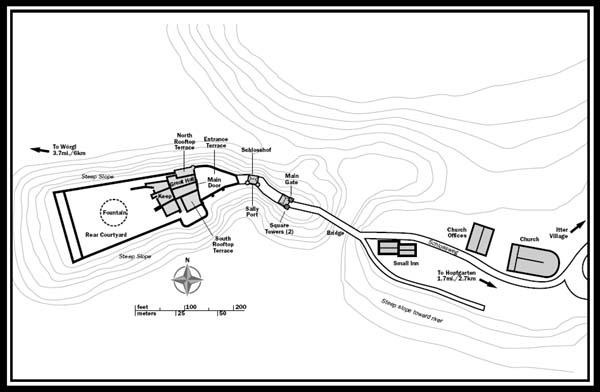

THE CASTLE THAT WAS SOON to figure so largely in Jack Lees life lay fourteen road miles to the southwest of where the young officer sat perched atop his tank. Schloss Itter, as its called in German, sits on a hill that commands the entrance to Austrias Brixental valley. The structure bestrides a ravine, with a short bridge linking the castle to the flank of the mountain. The village of Itter spreads out to the east from the castle, some 2,300 feet above sea level and nestled beneath Hohe Salve, the 6,000-foot mountain in the middle alpine region historically known as Tyrol.

Though it would be of little concern to Lee and his men in the coming hours, Castle Itter already had a long, rich, and often violent history. The surrounding area had been inhabited at least since the middle Bronze Age (1800 to 1300 BCE), and the fact that the valleys of the Inn and Brixental Rivers provide a fairly flat and direct route between Central Europe and the Italian peninsula ensured that Tyrol saw more than its share of conflict. Conquered by Rome in 15 BCE, the region was successively invaded by the Ostrogoths, various German tribes, and Charlemagnes Franks. In the ninth century CE Tyrol came under the sway of the Bavarians, who built two sturdy stone keeps and a surrounding wall atop the hill that would later be home to Schloss Itter, and in 902 a Count Radolt passed ownership of the fortified site to the Roman Catholic diocese of Regensburg.

Seeking to better protect his expanding Tyrolean possessionsand, of course, better enforce the collection of diocesan taxesRegensburgs Bishop Totu

Though ostensibly men of both God and peace, the bishops of Regensburg were also princes of the Holy Roman Empire. As temporal rulers the bishops were often heavy-handed and needlessly severe, and Schloss Itter saw frequent service as a base from which the bishops launched punitive expeditions against their sorely oppressed subjects. Though Tyrol came under Hapsburg rule in 1363, Schloss Itter and the nearby village remained within the ecclesiastical control of the Regensburg bishops until 1380, when Bishop Konrad VI von Haimberg sold them to the archbishop of SalzburgPilgrim II of Pucheinfor 26,000 Hungarian guilders.

Looted and partially destroyed during the 15151526 Tyrolean peasant uprising, It is also at about this timeand most probably at the order of those whose job it was to root out witchesthat the famous phrase from Dantes fourteenth-century epic poem Divine Comedy was first inscribed, in German, on the wall above the doors leading to Schloss Itters vaulted entranceway: Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.

The castle changed hands several times over the following two and a half centuries, and by 1782 was part of the personal lands of Joseph II, who had become Holy Roman emperor two years earlier following the death of his mother, Hapsburg empress Maria Theresa. So fond was Joseph of his Tyrolean fortress that when Pope Pius VI journeyed to Austria shortly after Josephs ascension to the throne, the monarch insisted that the pope consecrate the altar in Schloss Itters small but exquisite chapel. The pope did somainly in an attempt to heal a rift between Joseph and the churchand also left behind at the castle an ornate Gothic crucifix and other ecclesiastical treasures.