FORGOTTEN VICTORY

THE FIRST WORLD WAR: MYTHS AND REALITIES

GARY SHEFFIELD

Gary Sheffield, 2001

Gary Sheffield has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in 2001 by Headline.

This edition published in 2014 by Endeavour Press Ltd.

Twitter: @ProfGSheffield

Website: http://www.garysheffield-historian.com

To Viv, as always

Table of Contents

Preface

The First World War was a tragic conflict, but it was neither futile nor meaningless. Just as in the struggles against Napoleon and, later, Hitler, it was a war that Britain had to fight and had to win. This achievement has become obscured by myths. For instance, the image of the British army of 1914-18 as being inept, lions led by donkeys, is highly misleading. In fact, against a background of revolutionary changes in the nature of war, the British army underwent a bloody learning curve and emerged as a formidable force. In 1918 this much-maligned army won the greatest series of victories in British military history.

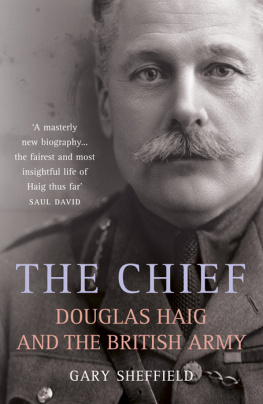

To many people, these views will appear bizarre, shocking or even offensive. This was forcibly brought home to me in 1996 when I appeared as a talking head on a BBC Timewatch television documentary on the British commander in chief on the Western Front, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. Provocatively entitled Douglas Haig: The Unknown Soldier, it was broadcast on 3 July 1996, two days after the saturation media coverage of the eightieth anniversary of the first day of the Battle of the Somme. In Britain the First of July 1916 is a day, more than any other, associated in the popular mind with the stupidity and futility of the Great War, and Haig is indelibly fixed as the Butcher of the Somme. The programme juxtaposed these traditional views of the war, eloquently put by the prolific Australian writer, John Laffin, author of British Butchers and Bunglers of World War One , with revisionist historians such as Professor Trevor Wilson of Adelaide University and myself.

My argument was that Haig was not a military genius (few commanders are), but nonetheless deserved to be taken seriously as the commander of the victorious army of 1918. The subtlety of my argument was the victim of the cutting room floor. Such is television; it is extremely difficulty to convey complex academic arguments that in the seminar room would be qualified with a plethora of howevers, buts and maybes, within the confines of a fifty-minute television documentary. On the following day, the programme was reviewed in virtually every national newspaper. To put it mildly, the television critics seemed unconvinced by the case put forward by the revisionist historians. Indeed, some expressed anger that anyone could say anything at all in mitigation of Haigs conduct: It seems that for eighty years weve had it all wrong ... Haig ... just learned a lot from the horror of the Somme. Some learning curve. All those crosses making points on his graph, commented one reviewer.

I received letters from angry viewers forcefully denouncing Haig and accusing me of misleading my military students (at the time, I taught in the Department of War Studies at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst). Interestingly, relatively few of my correspondents were of the variety familiar to most authors, the users of block capitals and red ink.

It is not difficult to understand the roots of my correspondents anger. The losses on the Western Front were the greatest ever sustained by a British army. The enormous casualties, the One Million Dead, left the people of the British Empire in a profound state of shock that has shaped perceptions of the war ever since. What was the point, it is asked, of the bloody battles of 1915-17? Why could the generals not fight decisive battles in the manner of Waterloo in 1815 or Alamein in 1942? The generals, it is commonly believed, were inept, and made terrible mistakes, resulting in huge loss of life. Furthermore, in hindsight we know that the First World War was not the war to end all wars, that an even greater struggle against the same enemy was to break out only twenty years later. All that effort, all that suffering, all those deaths, for what?

I am well aware that by advancing a contrary view, I am not merely engaging in academic debate: I am picking at a scar on the British national psyche that is still raw. This book is not an attempt to whitewash the generals or politicians of 1914-18. It is certainly not intended to glorify war. What it is is an attempt to shed the emotional baggage of the last eighty years and treat the First World War as an historical topic like any other.

Once I shared the common view of the First World War as a futile tragedy conducted by a gang of incompetents. Although I was born sixteen years after Germany and Japan surrendered, I was very much a child of the Second World War, which was usually referred to simply as The War. No one was in any doubt that the 1939-45 conflict had been a good war. Not only had it been just and righteous, it had also been won without an unduly heavy cost in lives (at least, Anglo-American ones). But from an early age I was dimly aware that before the good war there had been an appalling national catastrophe. The Second World War was all about tanks, aircraft and victories. The First World War was about infantrymen and machine guns and massacres of British soldiers. The generals had been unbelievably incompetent, I learned, and millions had died as a consequence of their folly. One had only to look at the war memorials that stand in every British city, town and village and compare the list of dead from the First World War with the much shorter list of dead from the Second. And for what purpose did they die? For nothing, it seemed, an impression strengthened by the first book I can remember reading on the war, A.J.P. Taylors The First World War. Viewed through the lens of the Good War of 1939-45 the struggle of 1914-18 seemed to be a very bad war indeed.

My simplistic views on both world wars did not long survive contact with the world of academic history. As a history undergraduate, I was soon exposed to arguments that undermined some of my cherished beliefs. In particular, I began to understand that there was a reason for fighting the war, and British strategy did make some sense, even if it did not always work. When I began postgraduate research, which involved extensive research in archives reading primary documents, even more scales dropped from my eyes. As I came into contact with other historians at institutions such as the War Studies departments at Sandhurst and Kings College London, the Imperial War Museum, and others in Australia, Canada and the USA, I discovered that there was an informal school of historians doing the hard work of archival research into the British army of the First World War. Although some influential writers such as John Keegan continue to take a very traditional, that is unfavourable, view of the British army on the Western Front and have little time for the revisionist school of historians, the composite picture that has emerged is of an army very different from the incompetent shambles of popular myth. Likewise, the work of many diplomatic and political historians points firmly away from the popular view that the war was a ghastly accident and instead underline that the war was fought over substantive issues.

For the last decade and a half I have sat in academic seminars in which historians have complained about the difficulty of shifting public opinion on these issues. It seems that every time an important new book comes out, another popular book or television programme appears repeating the same old tired myths. Clearly, a large part of the blame for the failure of revisionist history to become accepted by a wider audience lies with the historians themselves. Articles published in obscure learned journals or vastly expensive academic tomes are never likely to be widely read. Furthermore, until very recently, the study of battles and generals was not a popular or respectable field in most universities. Such frustration is not merely a matter of wounded professional pride, or jealousy at the sales of popular books on the subject. At the grand strategic level, the futility view has had an impact on national self-perception, and there is always the danger of decision-makers drawing flawed lessons from history. At the personal level there is the fate of the widow or orphan of a soldier, sailor or airman killed during the First World War. The loss of a loved one is bad enough. To be constantly told, quite erroneously, that he died for nothing must be even worse.

Next page