LIZZIE COLLINGHAM

The Taste of War

World War Two and the Battle for Food

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

For Sarah

Contents

List of Illustrations

Note on Sources

Throughout the book I refer to Mass Observation and the Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System. Mass Observation was set up in Britain in 1937 by the anthropologist Tom Harrisson, the sociologist Charles Madge and film-maker Humphrey Jennings, to record the views of ordinary people. During the war around 3,000 people responded to questionnaires sent out to them by Mass Observation and others kept diaries which they would send in to Mass Observation in instalments. These are now held by the Mass Observation archive at the University of Sussex and many have since been published in various collections. The names given to Mass Observation observers are pseudonyms. The Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System consists of transcripts of interviews conducted in West Germany in 195051 with refugees and defectors from the Soviet Union, most of whom were living in camps for displaced persons at the time. The interviews were conducted on behalf of the United States government in order to gain an understanding of communism.

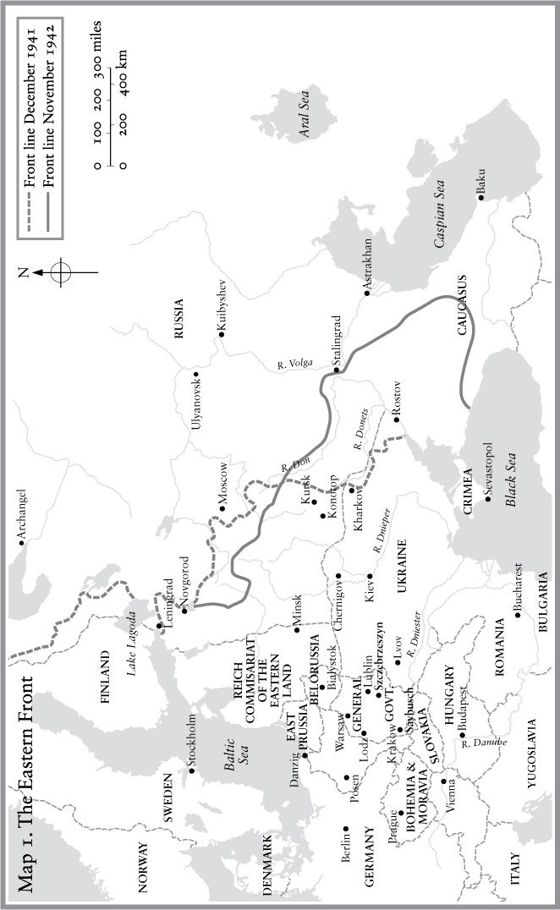

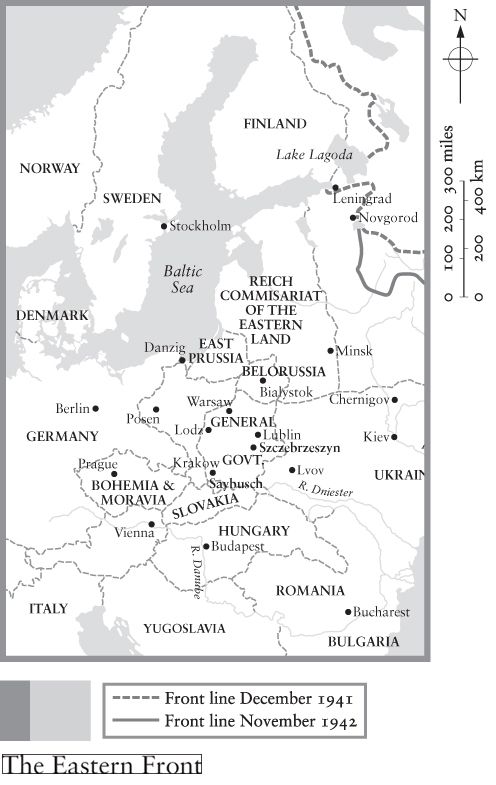

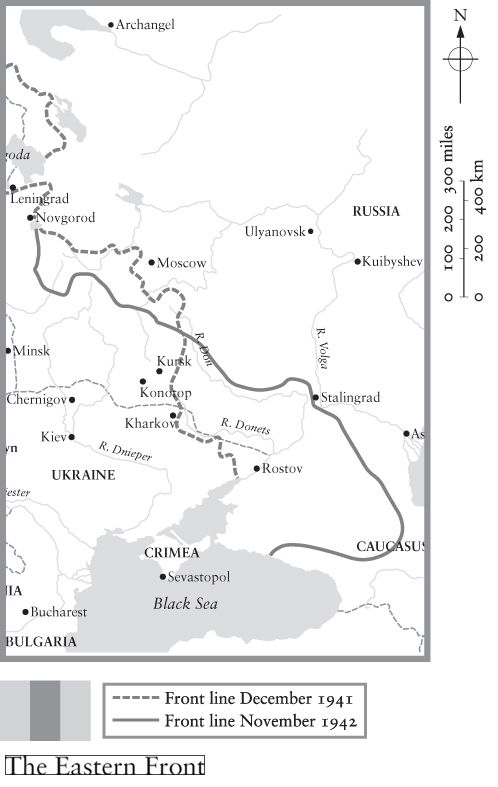

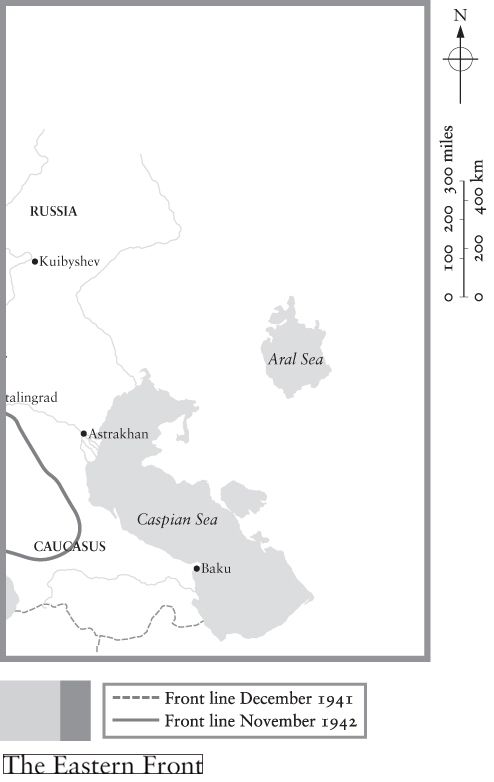

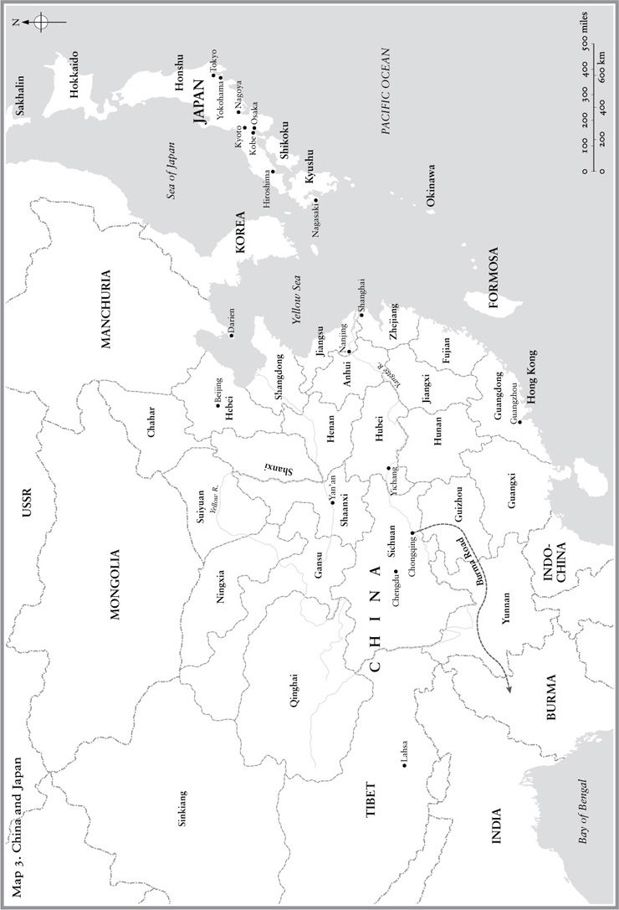

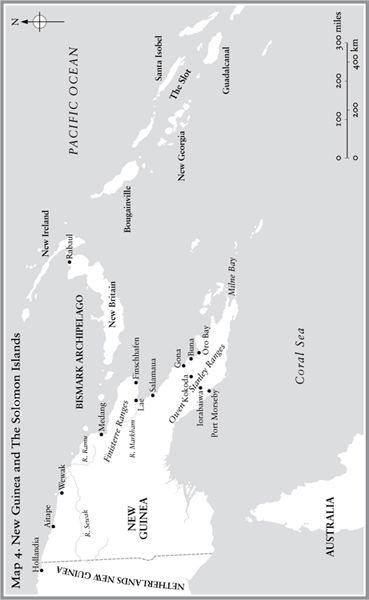

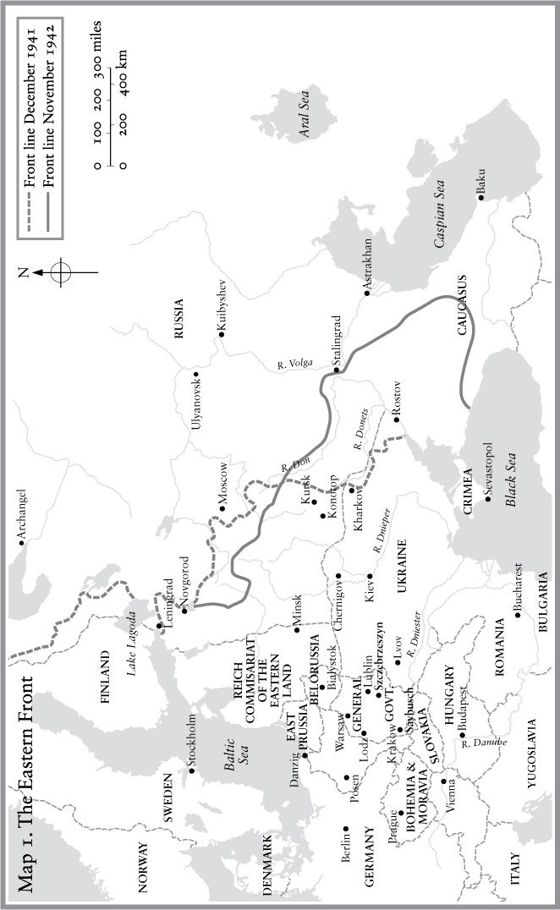

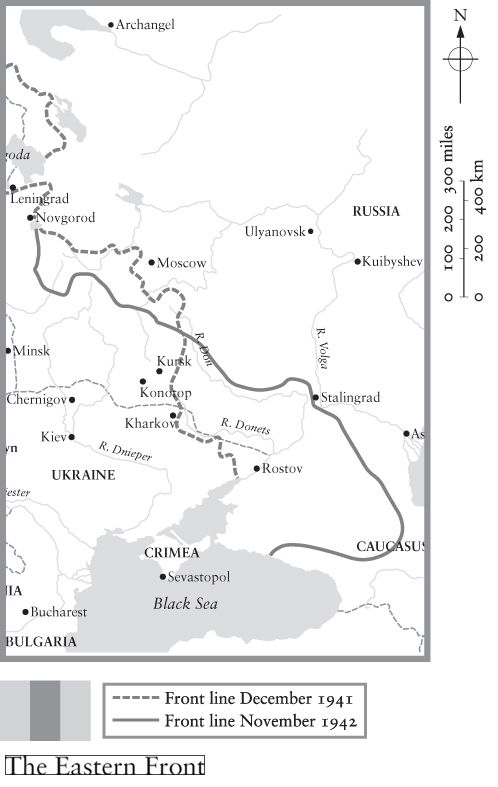

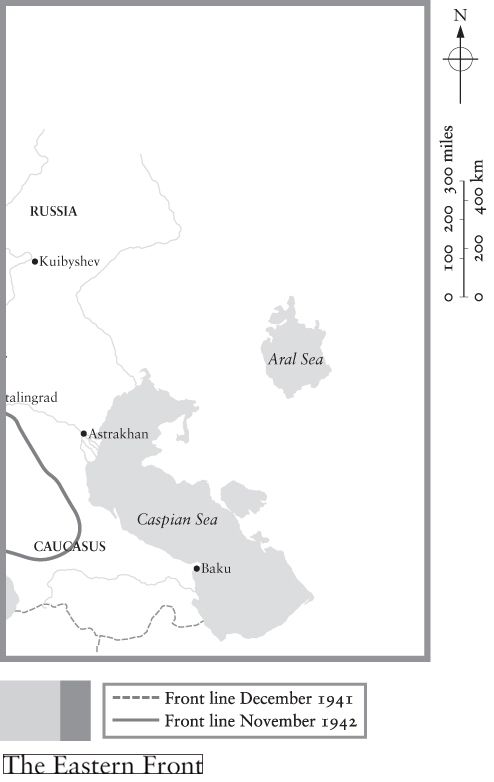

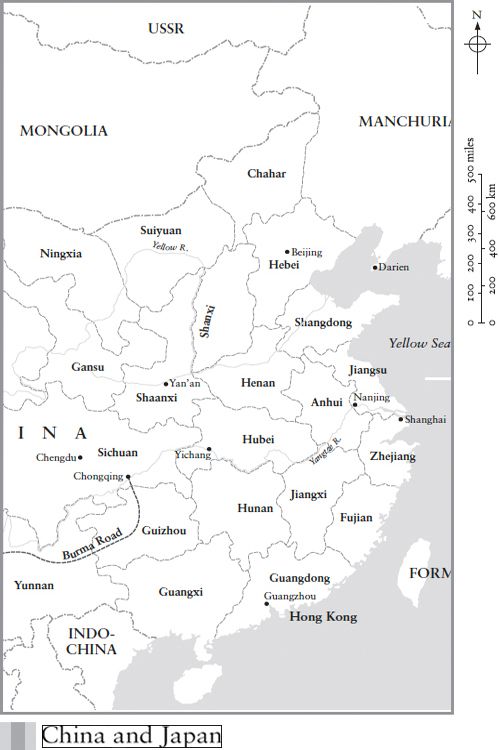

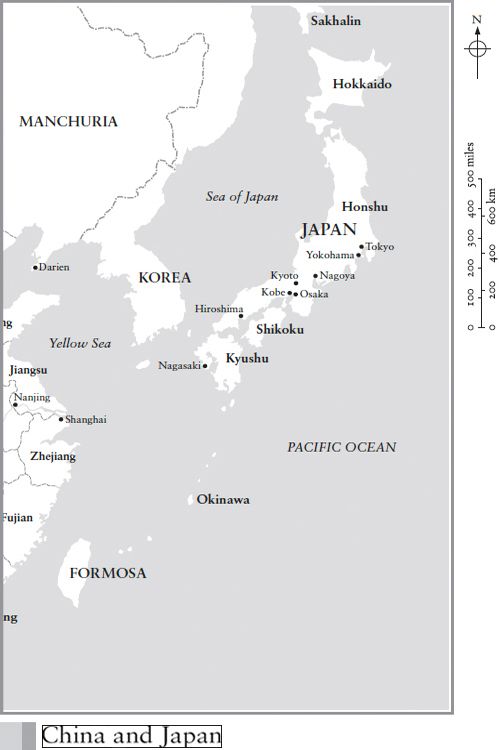

MAP 1

The Eastern Front

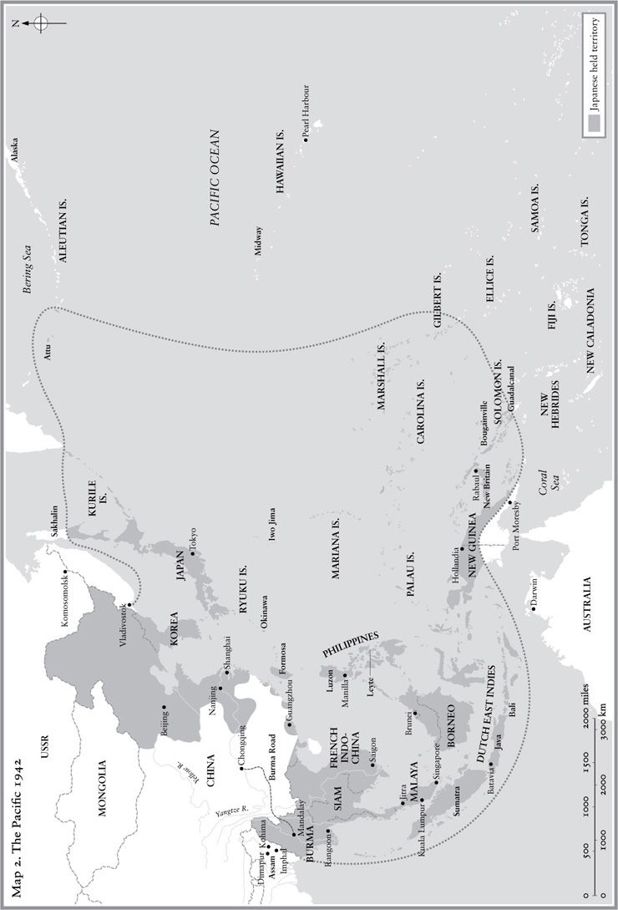

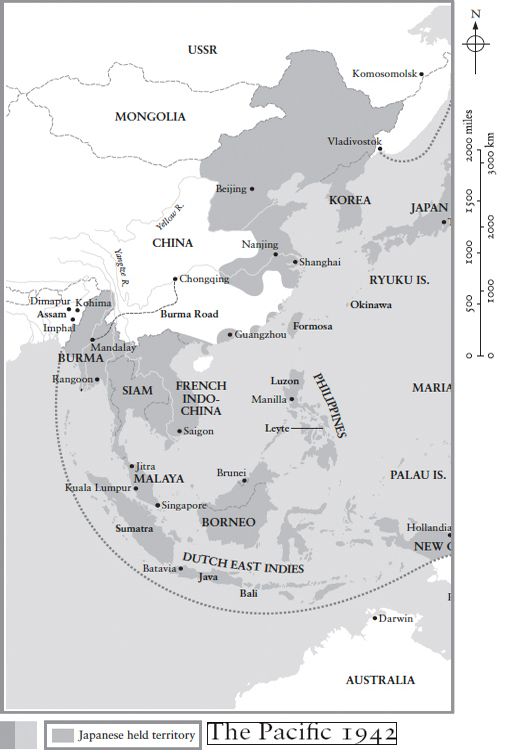

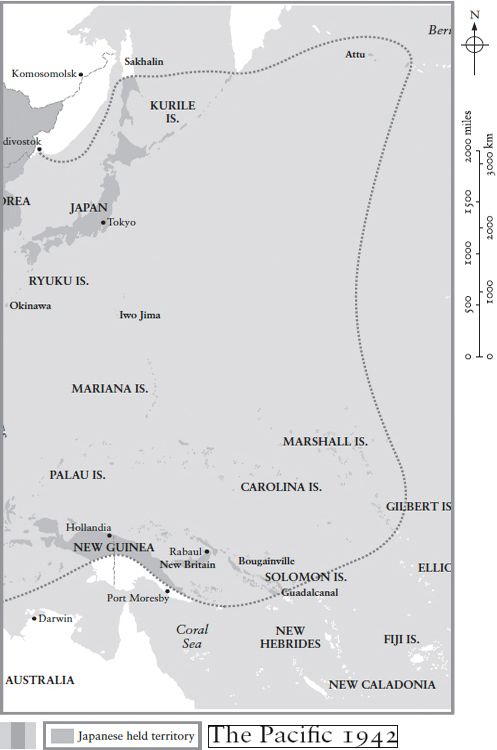

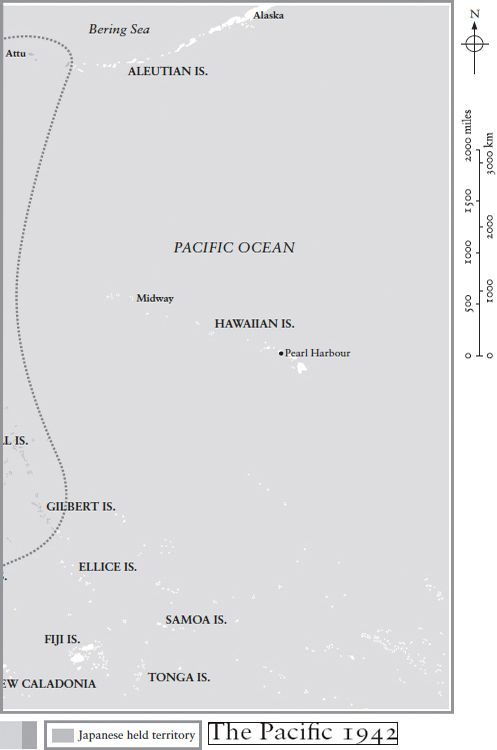

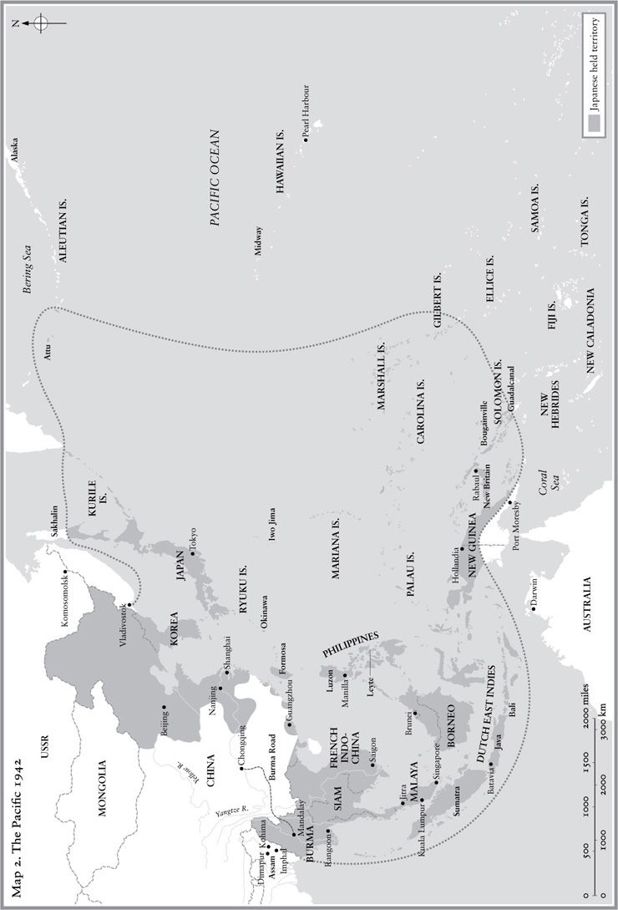

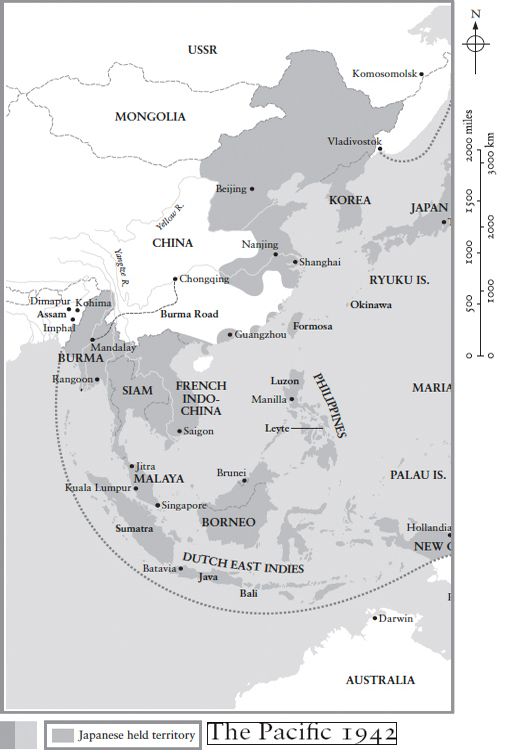

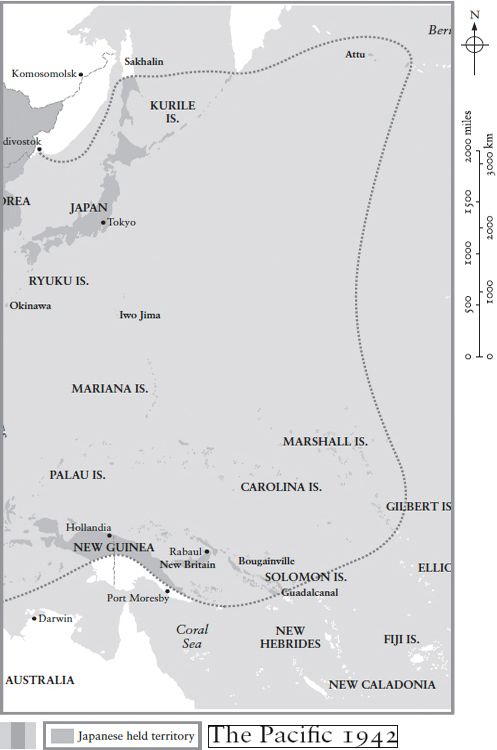

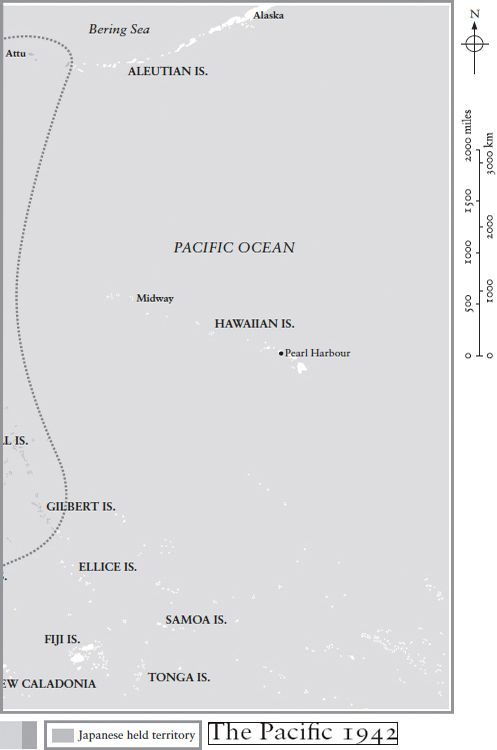

MAP 2

The Pacific 1942

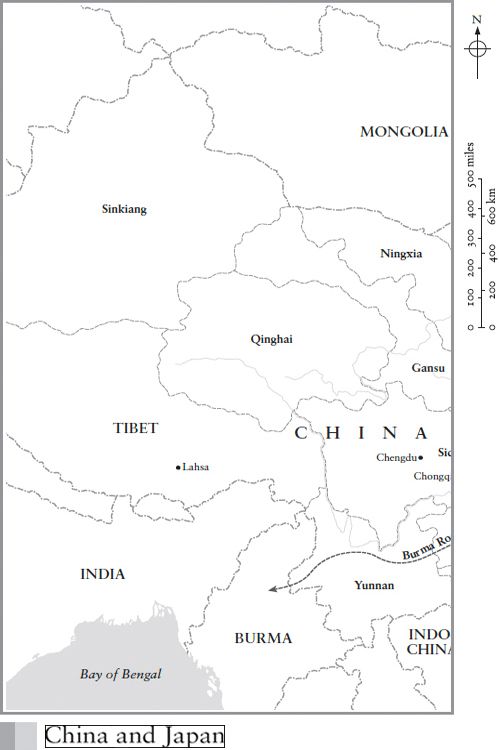

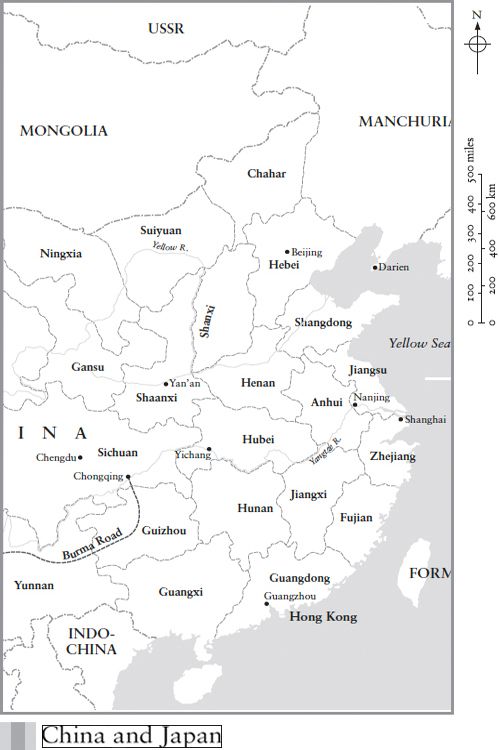

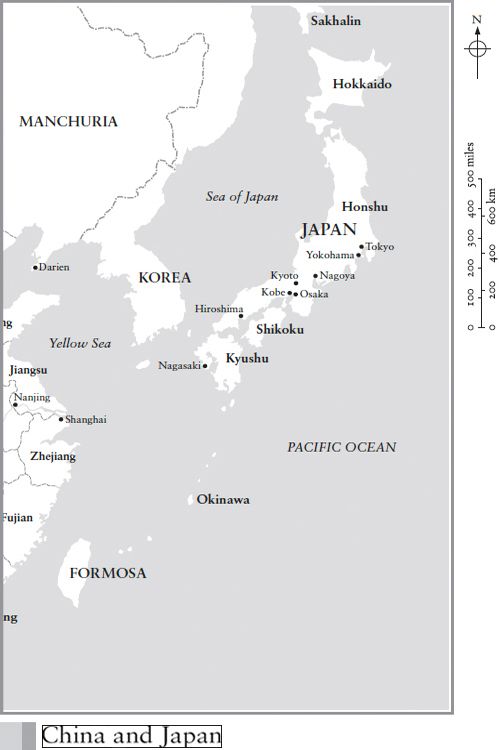

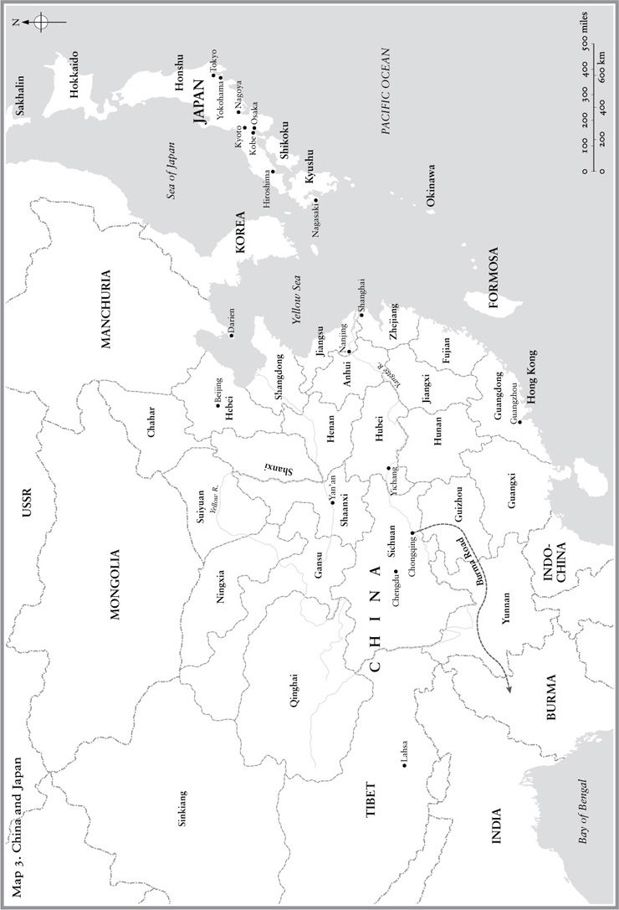

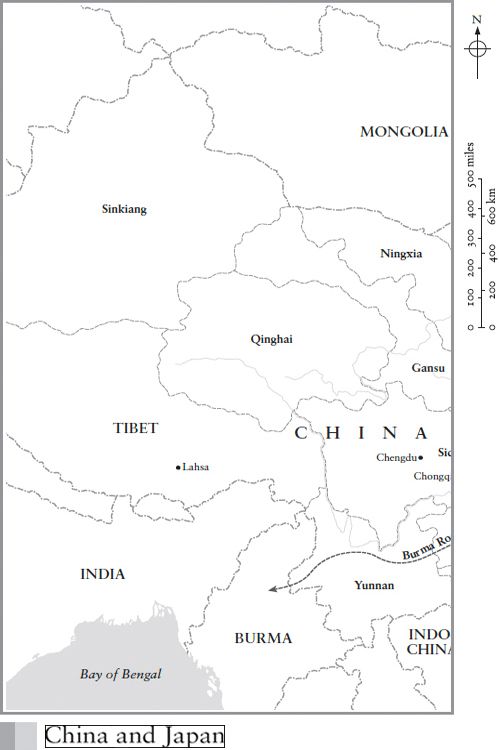

MAP 3

China and Japan

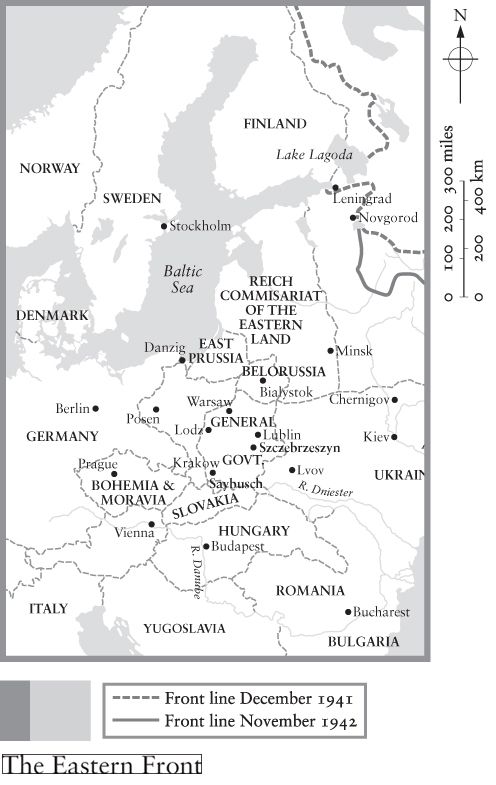

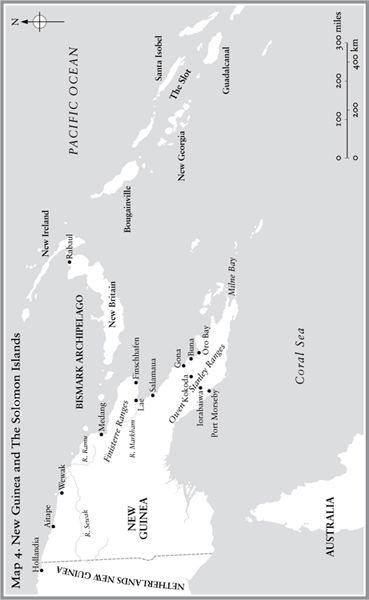

MAP 4

New Guinea and The Solomon Islands

1

Introduction War and Food

Death by famine lacks drama. Bloody death, the deaths of many by slaughter as in riots or bombings is in itself blood-bestirring; it excites you, prints indelible images on the mind. But death by famine, a vast slow dispirited noiseless apathy, offers none of that. Horrid though it may be to say, multitudinous death from this cause regarded without emotion as a spectacle, is until the crows get at it, the rats and kites and dogs and vultures very dull.

During the Second World War at least 20 million people died just such a terrible death from starvation, malnutrition and its associated diseases: a number to equal the 19.5 military deaths. The impact of the war on food supplies was thus as deadly in its effect on the world population as military action. This book seeks to understand the role of food at the heart of the conflict. The focus on food is not intended to exclude other interpretations but rather to add an often overlooked dimension to our understanding of the Second World War.

The book begins by uncovering the important role food played in driving both Germany and Japan into conflict. During the nineteenth century Europes urban industrial workforce substantially increased their consumption of meat, while the demand for rice rose significantly among Japans urban population. Both countries feared that their agricultural sectors could not produce enough food to feed the cities. Britain had responded to the problem of feeding its urban population by embracing free trade and it imported large quantities of food and animal fodder. But Germany and Japan felt disadvantaged by the international economy dominated by Britain and America. Right-wing elements within both countries pushed for an alternative, more radical solution to the problem of food and trade. Rather than accepting subordination to the United States, Hitler preferred to engage in a struggle for world supremacy and looked to an eastern empire as a source of food and other resources which would make Germany self-sufficient and independent of world trade. This made war in eastern Europe inevitable. The Japanese army sought to reduce its countrys dependence on the United States by consolidating its hold over mainland China which many officers saw as an area of settlement and resources, not the least of which was food. But Japanese belligerence in China set the country on a collision course with the United States in the Pacific.

This perspective on the causes of the Second World War is relevant to the contemporary global food situation. The problem which confronted Germany and Japan in the 1930s, of how to feed a growing urban population with the more nutritious but also more costly food which it demands, has returned to confront the developing world with even greater force and with the potential for an equally global impact at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Rising living standards among the growing urban middle classes in developing countries such as China, India, Indonesia and Brazil have led to marked changes in eating habits. Zhang Xiuwen grew up a member of a poor farming family in the rural province of Yunnan. He often went hungry and he only ever ate meat on special holidays once or twice a year. He never drank milk. Now he is a tennis coach in Beijing and he and his family can afford to eat meat and drink milk every day. This shift from a grain-based vegetarian diet to one rich in meat and milk has been replicated across China and the rest of the developing world, where hundreds of millions of consumers food preferences have changed as their nutritional status has improved. Chinese per capita consumption of meat has risen in the last twenty-eight years from 20 kilograms in 1980 to 54 kilograms in 2008. The wider impact of such changing tastes has been to divert ever more of the worlds grain harvest into the stomachs of animals rather than humans. In 2007 China imported 45 per cent of the soya beans traded on the world market to feed pigs, poultry and farmed fish. Approximately 30 per cent of the worlds grain crop is now fed to livestock.

Diverting grain from humans to animals is an extremely inefficient use of food. The 34.5 kilograms of grain that have to be fed to a steer to obtain half a kilogram of beef contain as many as ten times more calories and four times as much protein as half a kilogram of beef. As the world population and the worlds middle class continues to grow and food prices rise, this is likely to become an ever more pressing problem.

Next page