Table of Contents

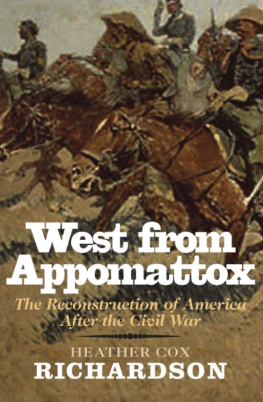

Praise for Heather Cox Richardsons Wounded Knee

In this provocative history Heather Cox Richardson traces the close linkages among late-nineteenth century politics, the West, and the horrendous Wounded Knee incident of 1890-91. No previous study has uncovered the full political account the author provides in this thorough, convincing volume.

RICHARD W. ETULAIN,

author of Beyond the Missouri:

The Story of the American West

With a mastery that brings even her bit players to life, Heather Cox Richardson has given us a fresh and vivid account of the greed, partisan politics, prejudice, and butchery that led to the massacre at Wounded Knee. The result is a superb book, history at its very best.

LEONARD L. RICHARDS,

author of The California Gold Rush

and the Coming of the Civil War

Heather Cox Richardson explodes the myth that the tragedy at Wounded Knee was simply an unfortunate accident or an outgrowth of cross-cultural misunderstandings on the frontier. Instead, she proves that the massacre emerged out of misguided federal Indian policies and, above all else, partisan politics. The story is chilling. Youll want to put it down, but because its so well told here, you wont be able to.

ARI KELMAN,

Associate Professor of History at

the University of California, Davis,

and author of A River and Its City:

The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans

For Lisa Adams and Lara Heimert

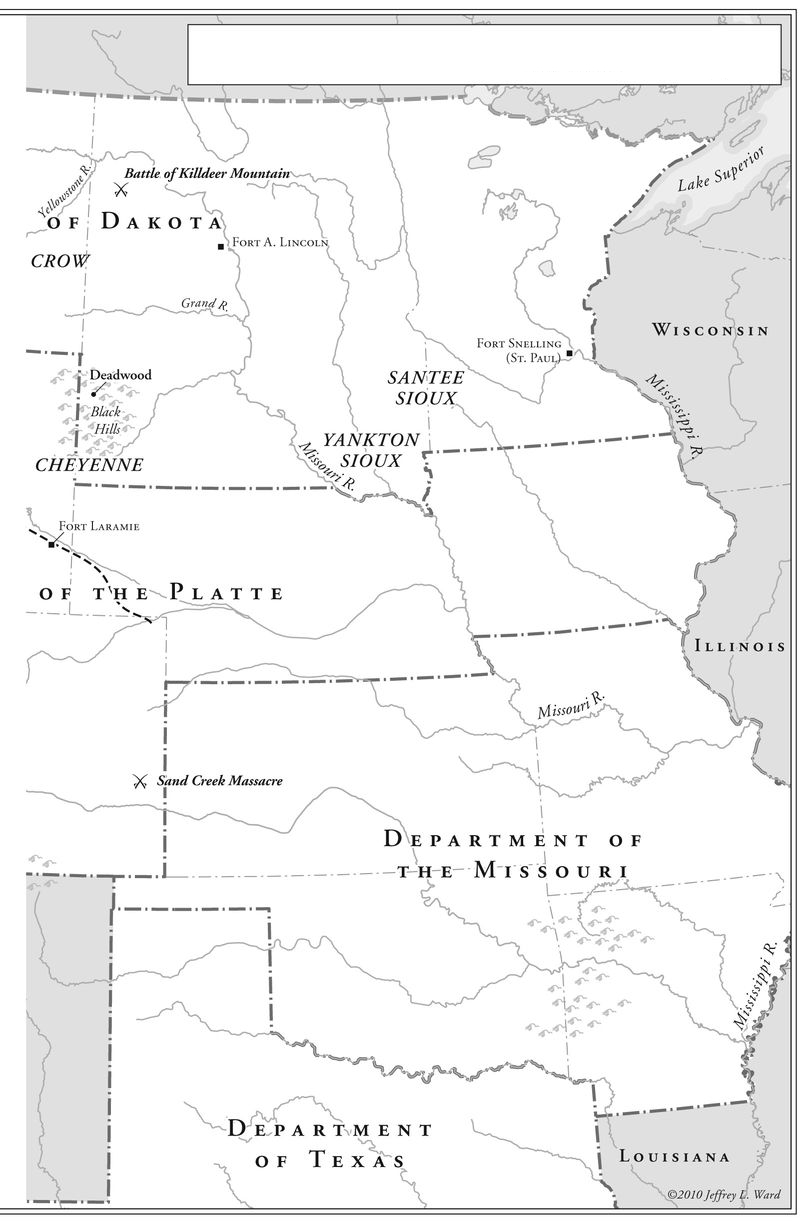

MAP OF U.S. WEST, 1866-1877

INTRODUCTION

The Sun Shone Forth Bright and Clear

ON SUNDAY, DECEMBER 28, 1890, novice Nebraska newspaper reporter William Fitch Kelley wrote with a light heart from an army camp on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. The Indian trouble of the last year was practically ended, he explained to the readers of the Nebraska State Journal. The day had dawned beautifully, and the sun shone forth bright and clear upon the camp of the Seventh Cavalry on Wounded Knee Creek.

Relief pervaded the camp. Since mid-November, troops from as far away as Kansas and New Mexico had come to South Dakota to prevent an uprising of Sioux warriors. This had been the largest military mobilization of the U.S. Army since the Civil War, involving fully a third of the army. About nine thousand soldiers had moved to South Dakota; of those, about five thousand had been stationed at the Pine Ridge agency.

Their arrival had panicked a number of the Sioux. When the soldiers had marched in, a band of thousands of Sioux warriors and their families had stampeded from their homes and holed up at a place called the Stronghold in the Badlands to the northwest. The soldiers had waited uneasily for weeks to see if the Badlands Sioux would fight or surrender. Indians and army scouts had made a number of forays from Pine Ridge to the Badlands to negotiate, and on this bright Sunday morning, reports had finally begun to indicate that the Badlands Sioux would come in to the Pine Ridge agency to surrender.

Only about a week before, another band had suddenly drawn the armys attention. Far to the north, on the Cheyenne River Reservation, a single group of about three hundred Minneconjou Sioux had been moving under army escort toward a fort where they would be held until things resolved in the Badlands. Unexpectedly, during the night of December 23, they slipped away from the officer in charge of delivering them to the fort and escaped south. These Minneconjous followed an old chief named Big Foot, well known as a cooperative negotiator, but also suspected of being hostile to the government. No one knew quite what the Minneconjous were up to in their flight, but officers had assumed the worstthat they were plotting to join the fighters in the Badlands and start a war.

In fact, the Minneconjous were not going to the Badlands. They were on their way to the Pine Ridge agency. The Indians at Pine Ridge had invited Big Foot to bring his negotiating skills there to help to calm the tensions between the Badlands Sioux, the reservation Indians, the army, and the government agents. The Minneconjous had decided to take up this invitation when rumor had reached them that they would be imprisoned if they stayed at Cheyenne River. They were worried about running from their army escort, but more worried that they were walking into a trap. Famous Oglala leader Red Cloud was at Pine Ridge, and they gambled that he could protect them from the army.

Army officers, anxious to make sure that Big Foots people could not join the warriors in the Stronghold, sent a detachment from Pine Ridge to intercept them whenever they could be found. Following orders, the soldiers moved about eighteen miles from the agency to Wounded Knee Creek. They had arrived at the Wounded Knee settlement two days before and pitched their tents, hammering iron tent pegs in straight lines across the unbroken land. They set up camp near the traders store and post office that were tucked into the sloping prairies under a few twisted cottonwoods.

The settlement was typical of those scattered across sparsely inhabited South Dakota. It took its name from the nearby Wounded Knee Creek, which flowed into the White River on the southwestern edge of South Dakota near the Nebraska border. In this part of the new state, the dry ground was carved by dozens of long, shallow creeks that meandered through the regions gentle hills before draining into larger rivers. Those rivers in turn poured into the mighty Missouri, which commanded the center of the state as it wandered from its northern roots to the southern border and beyond. With its bright white tents and its straight lines, the army camp squatted awkwardly on the rolling land. There the soldiers settled in, reluctantly accepting that they might be facing a long winter campaign.

But the troops had been at Wounded Knee only a day or so when important news arrived from the Pine Ridge agency. On the morning of December 28, the officers at Wounded Knee had received reports that the Badlands Sioux were coming in to army headquarters. This would effectively end the threat of a shooting war that had loomed for the past six weeks.

The troops who had been sent to Wounded Knee Creek rejoiced at the end of the standoff, but the morning was otherwise dull. They hung around and waited for scouts to locate the band of Minneconjou Sioux they had been sent to intercept. They performed the circle of their duties, then killed time as the chill prairie wind stirred the dust the army horses had churned up on the little-used road to the settlement. They likely speculated on where Big Foots band might be and on when the Indian troubles would be settled, so they might be able to go back to their home army posts.

South Dakota was a strange place to most of these men. Many were soldiers from the Seventh Cavalry, General George A. Custers old regiment, stationed since the 1880s in Kansas. Others were from even farther south and west. South Dakota might have sounded romantic in Custers accounts of exploring it fifteen years before, but men used to warmer regions with their forests, milder climates, and bustling cities found the state cold and isolated and inhospitable.