Dedicated to My Father and Mother

Ivan and Gloria Scherb

For giving me the world's stage to play upon

Acknowledgments

MANY PEOPLE HAVE OFFERED ME ASSISTANCE AND SUPPORT with this project, both in its early stages as a dissertation and through the process of revision. First of all I would like to acknowledge the assistance of the staff at the Norfolk Record Office in Norwich and the Suffolk Record Offices in Ipswich and Bury St. Edmunds. I would also like to thank Richard Beadle and Elsa Streitmann, both of Cambridge, Meg Twycross at Lancaster, and Ann Hudson at Oxford for their willingness to talk to an American graduate student.

To Gordon Kipling, who originally introduced me to East Anglian drama all those years ago, I owe a debt incalculable; as my dissertation director, he was unfailingly available, copious and prompt in his comments, and encouraging in the face of frequently inadequate drafts. Since then, he has continued to be a mentor, colleague, and friend. Also at UCLA, H. A. Kelly and Robert Hethmon provided numerous helpful suggestions, while fellow graduate student Douglas Sugano gave me support by sharing my interest in the early drama. V A. Kolve looked at early drafts of what eventually became chapters 1 and 2. I first familiarized myself with the early theater through David Bevington's magisterial Medieval Drama, and when I met that book's editor years later I found that he had the same erudition, charm, and critical eye that marked all his productions, and he too has encouraged me in my efforts. Many scholars, including Joanna Dutka, John Coldewey, and Martin Stevens, have answered my requests for information and inquiries about particular points, while Kathleen Ashley offered encouraging comments on the whole book. Clifford Davidson has also offered help and support, not least by publishing parts of chapters 3 and 5, as well as offering some detailed suggestions for the book's revision, many of which I have incorporated into the finished work. I'd also like to thank the editors of English Language Notes, English Studies, Comparative Drama, Themes in Drama, The Body and the Text, and Studies in Philology for permission to reprint parts of articles that originally appeared in these publications, and also the readers and editors at Fairleigh Dickinson University Press for suggestions and for helping me through the publication process.

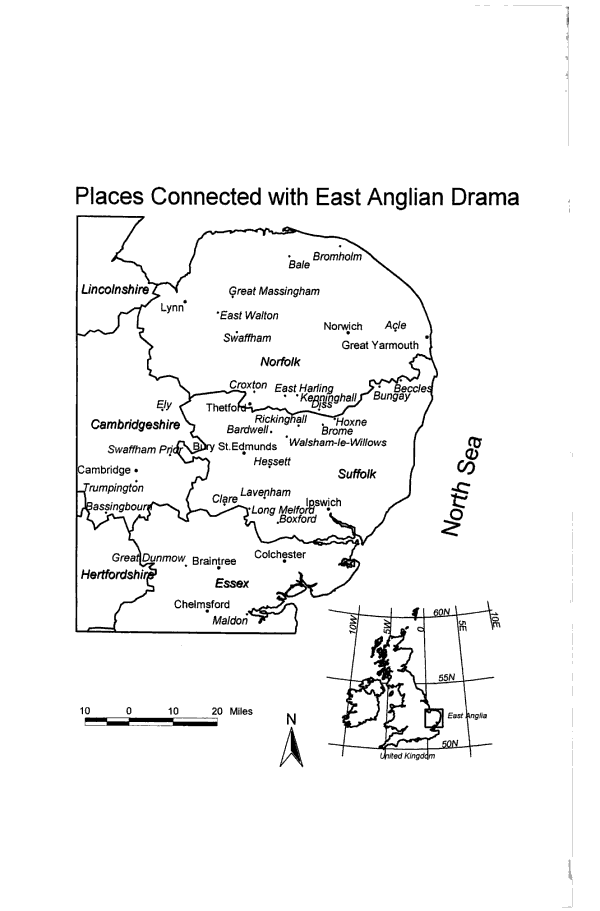

During my stay in Tyler, a university research grant allowed me time to do some much-needed revision, and I would particularly like to single out my colleaguesRoger Anderson, Robert Myers, Michael Murphy, Catherine Ross, and Lannom Smith for offering me both encouragement and a collegial atmosphere that aided me in the completion of this project. My thanks also to the overburdened interlibrary loan staffBeth Hogan and Howard Rockwellfor promptly fulfilling my frequent and obscure requests. Perhaps even more importantly, graduate student Silvana Vierkant's proofreading efforts were truly heroic and I appreciate them deeply. Jack Mills and Ken Rush of the Geographic Information Survey did a super job with the limited information I provided them in order to make the frontispiece map. Finally, I'd like to thank my students for their civility, interest, and intelligence, and most of all for their willingness to take their own leap of faith into the past.

Introduction

IN THE LATER MIDDLE AGES, THE NOUN "STAGE" COULD DESCRIBE any number of types of raised platforms employed for a public display, although either the spectators or the performers might well use such a "stage."1 Royal entries, tournaments, executions, and sermons could all be placed on a stage as well as drama. For example, in The Castle of Perseverance, a fifteenth-century religious play, a character named Detraccio asks Human Genus (Humankind) to look and see "where Syr Coueytyse sytt / And bydith us in his stage" (783-84). Here, the term plainly denotes a raised area where the actor playing Covetousness awaits the arrival of Humankind. The word could also be used as a verb, however, and this usage is also relevant to the character. Covetousness is in effect singled out for scrutiny by both the other characters and by the audience, literally "staged" by the physical circumstances of production. In a more modern sense of the word, too, the play is concerned with "staging" covetousness presenting it in a dramatic form in which it is visualized, enacted, and ultimately superseded. These varied usages evoke a complex configuration of associations concerning theatricality, aesthetics, society, culture, religion, and audience response. In late medieval religious drama, these issues are all closely, perhaps inextricably, intertwined, leaving faint traces in a handful of still surviving play texts, historical documents, and other kinds of cultural artifacts.

The title "staging faith" refers most directly to the performance orientation of this study, these plays being performed within a specific configuration of historical, cultural, and theatrical circumstances. East Anglian dramatic manuscripts contain abundant evidence of performance, particularly in their copious stage directions and marginalia. Local records document that physical stages were erected; even where physical stages were probably not used, playing places were found, whether in a hall, a church, or the street. In some cases, scaffolds were built for the players and representational structures were used. Although details are sometimes murky, East Anglian communities found producers, had scripts written, copied, and revised, assigned parts, purchased or made costumes, called rehearsals, arranged publicity, collected money, and gave performances before local audiences. This book studies how these playslargely from the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, all religious, and all with strong links to eastern Englandgave dramatic form to local religious impulses.

To take the phrase at its broadest definition, we can see that many individuals and many communities in pre-Reformation England attempted to stage their faith in a wide variety of ways: church architecture, funerary monuments, stained glass, painting, and sculpture, as well as more scripted cultural forms such as the liturgy, devotional processions and ceremonies, andthe particular focus of this studythe vernacular drama. Linguistic and manuscript analyses reveal that many of the surviving late medieval dramatic texts come from a relatively small area of England known as East Anglia. While East Anglian communities were by no means the only groups to put on religious plays in late medieval England, their texts are particularly valuable objects for study simply because of the number and nature of what has survived.

For much of the twentieth century, East Anglian theater was looked upon as the poorer cousin of the guild drama of the larger towns and, as a result, it remained relatively unexplored. For most students in the twentieth century, the cyclic plays from the Towneley, York, or Chester manuscripts to a large extent defined English medieval drama. Critics placed the English play cycles at the center of critical attention in terms of textual study, dramatic artistry, and the larger connections between the drama and cultural life.2 Such an emphasis resulted in valuable insights, but by largely ignoring the late medieval drama from Norfolk, Suffolk, and the surrounding counties, this approach also led to a rather skewed picture of English medieval dramatic practice, one that emphasized pageant wagons, guild sponsorship, comic naturalism, and typology. For most students of literature at the start of the twenty-first century, the cycle plays and Everyman define English medieval drama. Recent, popular versions of medieval plays (e.g., Tony Harrison's The Mysteries) have further reinforced this perception. Critical neglect has been magnified by the fact that East Anglian plays are rarely performed, in part because they lack the commercial sponsorship that would come from a strong association with a major civic center such as York or Chester. With the notable exception of The N-Town Play (per formed on a semiregular basis at Lincoln, largely because it was mistakenly identified with the medieval plays performed there), performances of East Anglian plays have been infrequent.