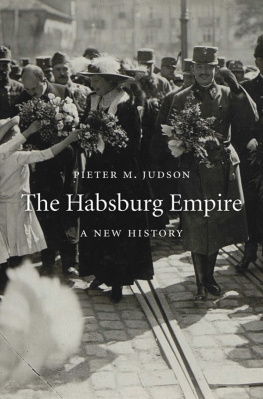

The Habsburg Empire

A New History

PIETER M. JUDSON

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

. 2016 .

Copyright 2016 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Design by Dean Bornstein

Jacket credit: sterreichische Nationalbibliothek

Jacket designer: Annamarie McMahon Why

978-0-674-04776-1 (cloth)

978-0-674-96932-2 (EPUB)

978-0-674-96933-9 (MOBI)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Judson, Pieter M., author.

Title: The Habsburg empire : a new history / Pieter M. Judson.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015036845

Subjects: LCSH: Habsburg, House ofHistory. | NationalismEurope, CentralHistory. | ImperialismSocial aspectsEurope, CentralHistory.

Classification: LCC DB36.3.H3 J83 2016 | DDC 943.6/04dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015036845

FOR CHARLES

CONTENTS

The subject of this book is a state that was known by many different names over the period 17701918. I refer to this state as the Habsburg Monarchy or Habsburg Empire. From 1804 until 1867 the state was known as the Austrian Empire. After the Settlement of 1867 the new dual monarchy was called Austria-Hungary. I refer to the western half of the dual monarchy as Austria, even though its official name was not Austria but rather The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Parliament [Reichsrat] (sometimes referred to as Cisleithania, while Hungary became Transleithania).

Writing about Habsburg central Europe in a way that does not reinforce a nationalist frame of reference is next to impossible. In recognition of this challenge, I try to refer to places with no common English names in the two or three languages their inhabitants used to name them. This practice may seem a cumbersome one, and nationalists may dispute the order in which I list those names, but it helps to challenge the assumptions that each of these places had a single authentic national identity. For places with common English names such as Cracow, Prague, Trent, or Vienna, I use the English version.

I try to avoid using normative terms like Czechs, Germans, Poles, or Slovenes, preferring instead descriptive terms like Czech speakers, even though this practice does not adequately describe the linguistic practices of many of its peoples. It does, however, return a modicum of agency to people who are otherwise often categorized in ways they might not have recognized. I use the term Hungarian and Hungarianization in places where others might use Magyar and Magyarization. Some scholars distinguish between a state-based concept of nation (Hungary) and a more ethnically inflected concept (Magyar), but this fundamental distinction makes little intellectual sense to me, especially in the context of the nineteenth century. For reasons of historical context I generally use the terms Ruthene and Ruthenian to denote the peoples and language that today are generally known as Ukrainian, although it is the case that by 1900 the term Ukrainian was becoming used more widely.

Except where cited in English-language works by other authors, all translations are my own.

Maps

Illustrations

On Tuesday the thirteenth and Monday the nineteenth of June 1911 in villages, towns, and cities across Imperial Austria, over four and a half million voters turned out to elect a new parliament.

Party newspapers urged readers who had not already done so to hurry to the local government office with official identification documents. Here they could pick up their voter-identification cards (Legitimation in German), which they should keep handy after they voted, in case their district held a run-off election. All warned against last minute chicanery devised by their opponents. Christian Social newspapers in Graz and Linz implored campaign workers to continue campaigning in every street and neighborhood of every district until voting ended. In Czernowitz / Cernui / Cernivci the bourgeois German, Romanian, Ukrainian, and Polish nationalist parties rallied their communities to unseat a Socialist incumbent. In Pettau / Ptui the Slovene-language Stajerc exhorted its readers as Voters! Farmers, Workers, and Craftsmen, urging them to unity behind its favored candidates in South Styria.

Prognosticators and candidates like to exaggerate the political stakes in any election. In retrospect, the stakes of this election in 1911 may not have been exceptional, but the level of excitement expressed in regional newspapers as well as the high turn-out rate on election day appear to reflect a high level of significance attributed by individual voters to the act of voting. One Social Democratic newspaper captured the essence of this significance, proclaiming, When you cast your ballot in the urn, you decide your own future.

As Austrians swarmed to their polling places to decide their own futures, they were well aware that they were also determining the future of their empire. Some of them even paid the ultimate price for their determination to vote, as shocked newspaper readers across the monarchy learned on 20 June, the day after the end of the voting. An election-day massacre had taken place the day before in the Galician oil town of Drohobych / Drohobycz. A crowd of Jewish and Ruthenian- or Ukrainian-speaking Galicians gathered in the town square determined to exercise their right to vote at the end of a bitterly contested parliamentary campaign. Many worried with good reason that the local authorities would try to fix the outcome in favor of incumbent Nathan Lwenstein and prevent them from voting for their candidate, Zionist Gershon Zipper. The former was the candidate of the towns Jewish powerbrokers and of the conservative elites of the Polish Club who effectively ruled the crownland of Galicia.

For this election the town bosses set up a single polling station to accommodate close to 8,000 potential voters. During the day the local police prevented anyone but known Lwenstein supporters from entering to vote. Several times mounted police drove restless crowds away from the voting station. Instead of doing their expected brisk sales from the presence of a festive crowd of voters, local shop owners experienced broken windows and collateral damage from the increasingly frustrated mob. Then, in the afternoon, the town bosses encouraged troops brought in from the Rzeszw garrison near the fortress at Przemyl to fire on the crowd. Twenty-six people died immediately, including women, the elderly, and children. Investigators later determined that most of the dead had been shot in the back, suggesting that they had been fleeing the troops.

This dramatically disturbing story does not simply illustrate the lengths that local political authorities were willing to go to maintain their power in an age of mass voter mobilization. It can also be read as a sign of the sheer intensity with which people in an industrial town far from Vienna and Budapest engaged politically and emotionally with their empire. This was only the second election held since the adoption of universal manhood suffrage for parliament in 1907, and only the third since the enfranchisement of men without property in 1897. Precisely for these reasons people treated the hard-fought right to vote as critical to their lives. Elections in the crownland of Galicia generally had a reputation for corruption at the time. The inhabitants of Drohobych / Drohobycz knew well that the men who ran their town would devise every possible form of chicanery to control the outcome of the poll. Nevertheless, an ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse crowd of working-class people was determined to elect its agreed-upon candidate. Zionists and Ruthene peasants may seem like unlikely allies, especially since we are used to hearing about conflict in Imperial Austria that pitted national or religious groups against each other. Both groups, however, cared deeply about this election to the parliament in far-away Vienna, even though this institution had much less influence over their daily lives than did the Galician government in Lemberg / Lww / Lviv and the local bosses who represented that regime. Why were the stakes so high, in both symbolic and real terms, for everyone in Drohobych / Drohobycz that day? What does this tell us about the place of the Habsburg Empire and its institutions in peoples lives?

Next page