PROLOGUE

Eight Crowns in Boulogne

1308

In the fourth week of January in the year 1308, the city of Boulogne-sur-Mer played host to the very top tier of European society. Camped in canvas tents around the city square were dozens of princes, barons, counts, earls, and dukes, and seven kings and queens, including Philip IV, the king of France; King Louis of Navarre; Marie of Brabant, the dowager queen of France; Albert of Habsburg and Elizabeth of Tyrol, the king and queen of the Romans (the confusing name given to the rulers of Germany while they awaited confirmation in the office of Holy Roman Emperor); Charles II, the king of Sicily; and Marguerite, the dowager queen of England. They had arrived to celebrate the marriage of the eighth monarch, twenty-three-year-old Edward II of England, to his twelve-year-old bride, Isabella, the daughter of the French king, thus concluding a treaty and betrothal made five years earlier.

The most notable sovereign missing from the ceremony was the new king of Scotland, Robert the Bruce, whose absence was explained by the fact that he was, at that time, engaged in what would be a three-decade-long war to secure Scottish independence from England... and while Edward was pledging himself to Isabella, Bruce was managing a campaign that would, in a matter of months, leave him in control of a fifth of his enemys country.

Over the course of the next twenty years, the lives of virtually everyone in northern Europe would be powerfully influenced by a dizzying game of war, succession, diplomacy, and rebellion played out in Scotland, England, France, Flanders, and Germany by the monarchs in attendance at the wedding. The French would invade Flanders, and recognize Bruces sovereignty in Scotland. The death of the king of the Romans would lead to an eight-year-long struggle for his throne. Eventually Edwards child bride would leave her new realm for her native land, later to return at the head of an invading army that would force her husband to abdicate in favor of her son.

None of this, of course, was much in evidence at the royal wedding. The most notable thing about the ceremony, in fact, was the unseasonable weather. As the thirteenth century turned into the fourteenth, daytime January temperatures in Boulogne had averaged about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, and perhaps 10 degrees colder at night, and had been doing so for centuries. At Edward and Isabellas wedding, the barons and earls sleeping in those hundreds of tents shivered to nighttime temperatures well below freezing. The freeze they were enduring was covering virtually all of Europe; ports along the Baltic were frozen in for the second time in the preceding five years.

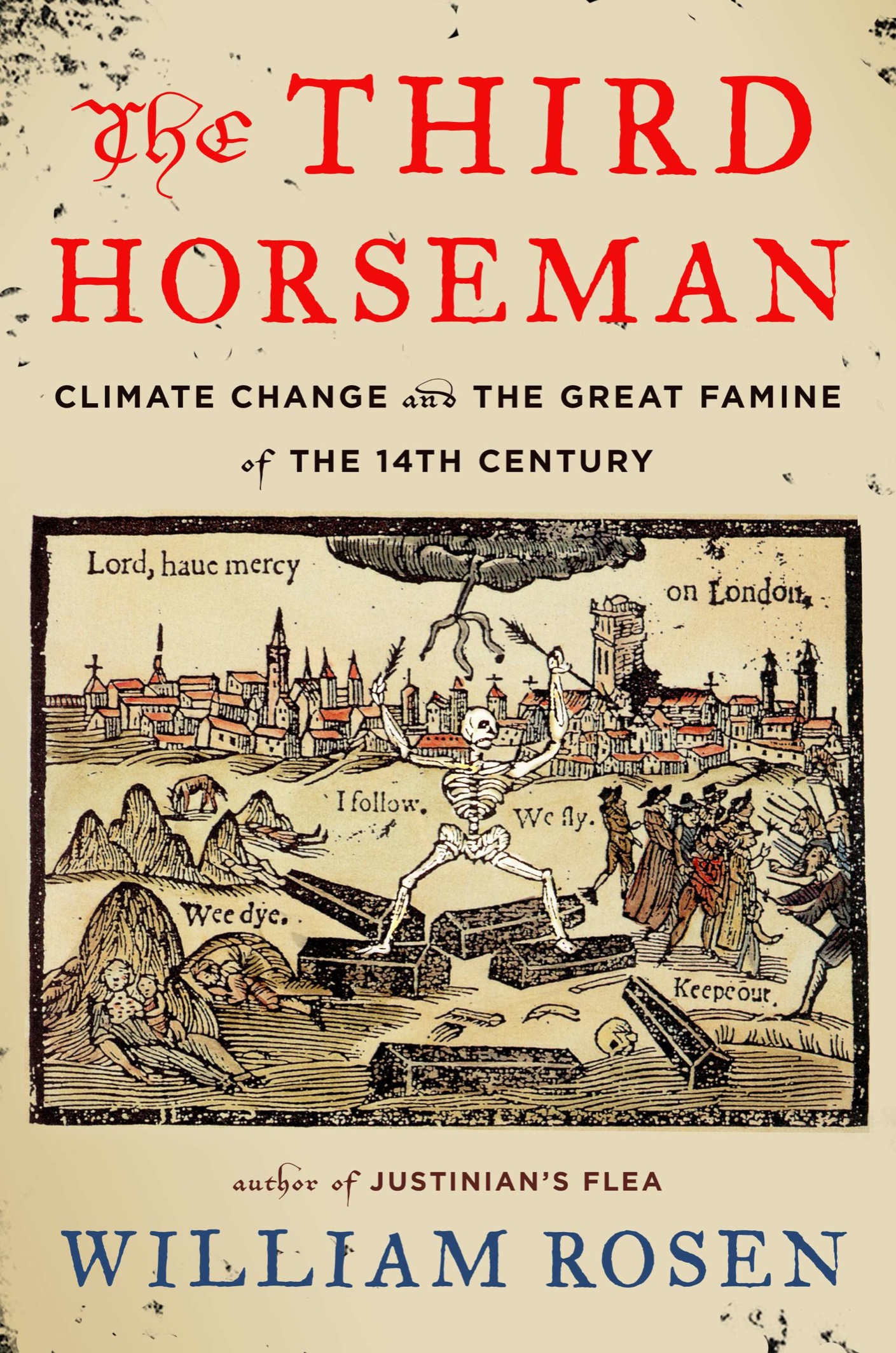

The weather was changing. More than that, the climate was changing, and changing in a way that would affect the lives of millions, often enough by bringing those lives to an untimely end.

The great conceit of history is that humanitys worst disasters occur within some identifiable and discrete time frame. Whether describing the arrival of a pandemic plague fifteen hundred years ago, or the world wars of the last century, conventional narratives offer a clear beginning and a decisive conclusion. The reality is more like a bridge collapsing: A minutes-long climax of forces that have been yearssometimes centuries or even millenniain formation.

So it was with the events that transfixed northern Europe during the first decades of the fourteenth century. Less than a decade after the wedding ceremony at Boulogne, the most widespread and destructive famine in European history brought privation and starvation to millions. Its proximate cause was a series of what seemed, to its victims, to be isolated and unpredictable weather events: summer storms and freezing winters. Its true origins were an almost incomprehensibly complicated mixture of climate, commerce, and conflict, four centuries in gestation, that put tens of millions of men, women, and children in the path of apocalyptic disaster. Those elements can no more be understood in isolation than one of the great medieval tapestries can be appreciated by listing each of the threads that compose it.

When such a tapestry is viewed from an appropriate distance, however, the picture comes into focus. From Europes ninth century onward, the great theme at center stage was the most basic of all: How should a society feed itself? What political and cultural system can allocate, protect, sow, and reap the land that was the ultimate source of food? For Europe, during the four centuries before Edward and Isabella stood before a priest on that cold day in 1308, the answer was a pacta contract sanctioned by law, and sanctified by religionthat bound the laborer to the land, and the landlord to the laborer.