Saints and Heroes Since the Middle Ages

by

George Hodges

Yesterday's Classics

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Cover and Arrangement 2010 Yesterday's Classics, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

This edition, first published in 2010 by Yesterday's Classics, an imprint of Yesterday's Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Henry Holt & Co. in 1912. This title is available in a print edition (ISBN 978-1-59915-094-9).

Yesterday's Classics, LLC

PO Box 3418

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

Yesterday's Classics

Yesterday's Classics republishes classic books for children from the golden age of children's literature, the era from 1880 to 1920. Many of our titles are offered in high-quality paperback editions, with text cast in modern easy-to-read type for today's readers. The illustrations from the original volumes are included except in those few cases where the quality of the original images is too low to make their reproduction feasible. Unless specified otherwise, color illustrations in the original volumes are rendered in black and white in our print editions.

Contents

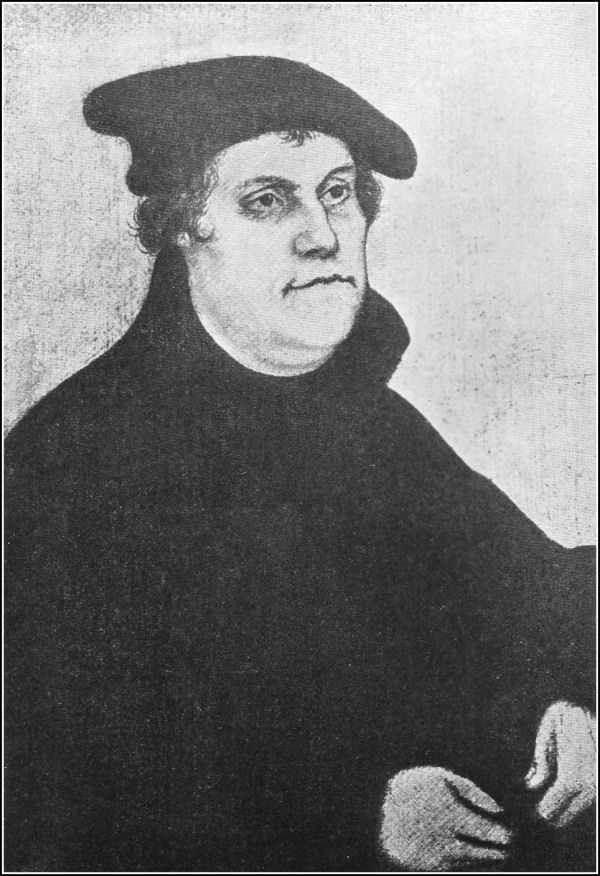

Luther

1483-1546

O N the last day of October, in the year 1517, a German monk posted a paper on a church door in Wittenberg. It was written in Latin, and was addressed to theologians. It contained a series of statements concerning the doctrine and practice of indulgences. The writer desired to have the matter discussed. It seemed to him that there was something wrong about it, and he would be glad to hear what wiser men might say. Here, he said, are indulgences preached and sold throughout the Church; is it right? is it in accordance with the gospel and the truth? The paper was a question.

Now the meaning of an indulgence was this. Every sin deserves the punishment of God. The sure consequence of sin is eternal suffering in hell. But by the grace of God, and the cross of Christ, and the ministry of the Church, there is a way of escape. Every sin may be forgiven, if the sinner is truly sorry and repents. In order, however, to obtain this forgiveness, the repentant sinner, they said, must confess his sin to a priest, and be, by him, assured of the pardon of God, and in addition must do what the priest tells him as a penance. The priest, in the old time, told him to fast, or to give money to the poor, or to go on a pilgrimage. In the days of the crusades, sinners were told that, in the place of the former penances, they might enlist as soldiers in the armies which were going to the Holy Land to take Jerusalem from the Turks. By-and-by, they were told that they might be assured of forgiveness if they paid the expenses of somebody else who was willing to go in their place. Then they were told they might gain the same blessing by giving money for some other good purpose; for example, for the building of a church. These substitutes for the old penances were called indulgences.

Gradually and naturally, this doctrine gave rise to grave errors and evils. One of the errors was that simple and ignorant people believed that the forgiveness of God was gained, not by repentance, but by indulgence. If they sinned, they could make it right, they thought, and escape punishment, by the payment of money. And this payment, they imagined, would affect them, not only in this world, but in the world to come; and would obtain pardon not only for themselves, but for others who had gone already into that other world. One of the evils was that this error was made a means of raising money for the Church. People gladly paid for the building of cathedrals and monasteries in the belief that they were thereby gaining forgiveness for their sins, and salvation for their souls and for the souls of their friends.

So when Pope Leo X wished to raise a great sum of money for the rebuilding of St. Peter's Church at Rome, he undertook to do it by the sale of indulgences. It seemed as right in those days to build a church by means of indulgences as it seemed right in this country a hundred years ago to build a church by means of lotteries. The raising of this money in Germany was put into the hands of man named Tetzel. He was a frank, straightforward person, with a better head for business than for religion, but with a great ability to appeal to the people. He knew how to speak to crowds. Tetzel took the doctrine of indulgences as he found it, and used it, as the phrase is, for all it was worth. He went about as a revival preacher goes to-day, having preparations made for his coming, enlisting all the ministers of the place, and holding great meetings. But his purpose was simply to get money. He began by preaching about sin and about hell. Now, he said, what have you done? All sins may be forgiven. Here is the promise of the pope, here are letters of indulgence, here is the opportunity for a little money to save your souls. And your friends,perhaps you have a father or a mother, perhaps you have children, gone into the other world, in purgatory,you may save them also. "Do you not hear your dead parents crying out, 'Have mercy upon us? We are in sore pain and you can set us free for a mere pittance?' "

This was what Martin Luther had in mind when he posted his paper concerning indulgences on the church door in Wittenberg.

Luther was already one of the foremost men in the Church in Germany. Born the son of a miner, among hills filled with copper, he had made his way by his own efforts through school and college, and had begun to study law. Suddenly, amid the terrors of a thunderstorm, he had changed his mind and had given himself to the ministry. He had entered a monastery in Erfurt. There he had gone through long seasons of deep depression, trying to save his soul by fasting and pain and prayer. For days he went without food, for nights he went without sleep, hoping thus to gain the good-will of God. He was terribly afraid of God, and feared that he would be lost at last in the torments of hell. But in the monastery he found wise advisers. One good brother said, "Martin, you are a fool. God is not angry with you; it is you who are angry with God." Another good brother, Staupitz, the head of the monastery, to whom Luther cried, "Oh, my sin, my sin, my sin!" replied, "You have no real sin. You make a sin out of every trifle." Staupitz urged him to trust in the mercy and love of God who freely forgives those who put their faith in Christ. He saw also that what Luther needed was an active life, and to be occupied, not in thinking about himself, but in ministering to others.

Then Staupitz became dean of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg, and he called Luther out of the monastery to be professor of logic and ethics. Presently he sent him on an errand to Rome, to see a bit of the great world. On his return Luther took his degree of doctor of divinity, and began to preach in the city church. He was appointed to teach theology to the young monks in the Wittenberg monastery, and men came to be instructed by him till the place was overcrowded. When he was but thirty-one he was made district-vicar, and put in charge of eleven monasteries. His hands were full of business. Then Staupitz made him his successor, in the chair of biblical theology.

There was already a new interest in the study of the Bible, and Luther entered into his new duties with enthusiasm, learning Greek and Hebrew, and reading all the latest books. He was at the same time the most popular preacher in the town, and the most popular professor in the university; and his fame began to go abroad. He had a practical mind, and was interested, not only in doctrine, but in conduct. And he had a remarkably strong and free and original way of expressing himself. Thus he criticized the common way of thinking about the saints. Instead of trying to be like them, people were praying to the saints to help them. "We honor them," said Luther, "and call upon them only when we have a pain in our legs or our head, or when our pockets are empty."