Peter Beale

AUSTRALIAN TANKS IN WORLD WAR II

The role of the tank in the First World War was clear. It was a recently developed weapon to crush barbed wire and knock out enemy strongpoints, particularly those containing machine-guns, and it achieved these two objectives successfully. By 1918 the performance of the heavy tanks had improved and was continuing to improve, and the lighter Whippet tank had also deployed successfully. The sudden end to the war on 11 November 1918 put tank development and the formulation of doctrine very much on hold.

This had two effects on the Tank Corps. The first was that resources to develop new tanks were very limited, and the second was that there was no opportunity to test changes to tank doctrine in real battles against hostile forces. Tank development went in all directions, and a large number of designs were proposed, many going no further than the drawing board. There were several views on the best way to use tanks, but evaluation was considerably hampered by uncertainty about the type of tank that would be available, a scarcity of resources to conduct exercises, and no opportunity for battle experience. Up to 1939 any formulation of tank doctrine by the Royal Tank Corps was purely theoretical.

Tank doctrine had to be learnt the hard way in World War II and, most of the time, it was unsuited to the reality of the war. Major General Pip Roberts served at many levels of armoured command after 1939. In 1944 he was commanding the 11th Armoured Division, and commented that it was not until the third battle in Normandy that they finally got the doctrine right. Illconsidered doctrine had resulted in the loss of many battles and the slaughter of tank crews and soldiers from the arms they were supposed to be supporting, particularly the infantry.

The Australian Armys experiences with tanks in the First World War were mixed: very bad at Bullecourt and good at Hamel and some later battles. Between the wars, the Australian tank arm was a very small component of the Army, and there was no officer of sufficient rank or experience to advise Army Headquarters concerning what could or should be done in respect of tanks.

This book traces the development of the Australian Armoured Corps, the design and production of its own Armoured Cruiser tank the Sentinel and the employment of tank units. It examines the projects to create an armoured division and build the Sentinel, both of which were slow in starting, but once commenced proceeded with exceptional speed and skill. As with all projects, timing is vital. Delay in starting may mean that the project outcomes are achieved too late to be of value.

The 1st Australian Armoured Division never saw action, and the Sentinel tank project was abandoned, even after some brilliant design and production efforts. There were several reasons for its abandonment, including the outbreak of war with Japan, the slow start to both projects, and the baleful influence of British tank doctrine. The question remains as to whether anything could have been done to prevent this waste of time and resources. A second, more pertinent issue concerns what the Australian Army has learned from this experience that will assist in the conduct of future operations. Answers to these questions form the central theme of this book.

On 5 May 2005 I was awarded a grant by the Australian Army History Unit (AHU) to produce a research paper An evaluation of the use of armoured forces by the Australian Army in World War II. My wife Shirley and I commenced research immediately and, later that year, presented a progress report to Roger Lee of the AHU. We were delighted when he offered us a contract to turn the research into a book to be published by the AHU.

We were able to concentrate almost full time on completion of the book, during which time we received help from many sources. These included the staff of the AHU and the staffs of the Australian War Memorial Research Centre and the National Archives of Australia. Christopher Dawkins at the Australian Defence Force Academy Library was a tower of strength, as was David Fletcher at the Tank Museum in Bovington. Lieutenant Colonel Todd Vail was particularly helpful in providing information about the procedures of the Australian Army, and Ric Pelvin and I journeyed along the lengthy process of editing together.

Above all, I want to thank my wife, Shirley, for the help she gave in our joint research at various archives, help that was given with patience, dedication and love.

Peter BealeApril 2011

The Malay Barrier. This was the name given to the arc of islands beyond the northern coastline of Australia, and included the islands of Borneo, Celebes, Ambon, Timor, Java, the Solomons and many others.

Chapter 1:

NATIONAL SECURITY AND TANKS

In the late 1930s and early 1940s the governments of Australia faced grave threats to the nations security and were forced to make critical decisions concerning their national objectives. National objectives are the fundamental aims or goals of a nation towards which a policy is directed and the efforts and resources of the nation are applied. The security of the nation is among the most important of these national objectives and the armed forces of the nation are major instruments in achieving those security objectives.

In 1939 both Australia and Britain employed their armed forces as an instrument of defence policy in three priority areas. For both nations the first priority was the defence of their home territory, the British Isles and the mainland of Australia respectively. The second priority was the security of other countries, allies or colonies for which Australia and Britain were responsible. Australias dependencies comprised the islands to its north, primarily New Guinea. Britain, on the other hand, was responsible for the defence of its vast empire which required a considerable portion of its armed forces. The senior members of the empire were India, Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand, all of which made substantial contributions to their own security and that of the empire, but still relied on Britain for support. The British Navy acted as a potent reserve and fortress Singapore contributed indirectly to the defence of India, Australia, and New Zealand.

The third priority for both Britain and Australia was to provide a force to fight alongside their allies against their common enemies. Britain had provided such an expeditionary force for many years, as evidenced in the exploits of Marlborough in Europe, Wellington in Spain, Raglan in the Crimea, Roberts and Kitchener in South Africa, and the forces that fought outside the British Isles from 1914 to 1918.

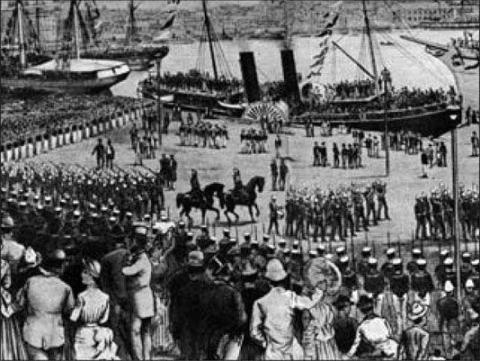

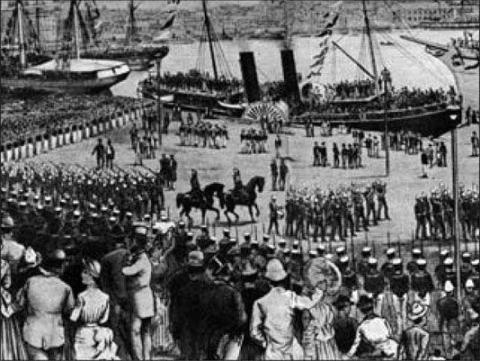

Sydney, 3 March 1885. The first Australian force sent to fight overseas as an organised unit was the Sudan Contingent. They supported British troops sent to avenge the death of General Gordon at Khartoum (

Melbourne Argus, 5 May 1885).

Australias first expeditionary force took the form of a contingent sent to the Sudan in 1885 and was followed in 1899 by a much larger force that fought in the South African or Boer War from 1899 to 1902.1

In the 191418 war, a very large contingent of Australians fought overseas at Gallipoli, in northern France and Belgium and in Palestine. At that time there appeared to be no significant threat to the Australian mainland. China was hopelessly disorganised, Japan was an ally and all the other countries in the South-west Pacific were colonies of France, Holland, or Britain. The number of troops required for the defence of Australia was relatively small.

The Malay Barrier. This was the name given to the arc of islands beyond the northern coastline of Australia, and included the islands of Borneo, Celebes, Ambon, Timor, Java, the Solomons and many others.

The Malay Barrier. This was the name given to the arc of islands beyond the northern coastline of Australia, and included the islands of Borneo, Celebes, Ambon, Timor, Java, the Solomons and many others.

Sydney, 3 March 1885. The first Australian force sent to fight overseas as an organised unit was the Sudan Contingent. They supported British troops sent to avenge the death of General Gordon at Khartoum (Melbourne Argus, 5 May 1885).

Sydney, 3 March 1885. The first Australian force sent to fight overseas as an organised unit was the Sudan Contingent. They supported British troops sent to avenge the death of General Gordon at Khartoum (Melbourne Argus, 5 May 1885).