PALESTINE

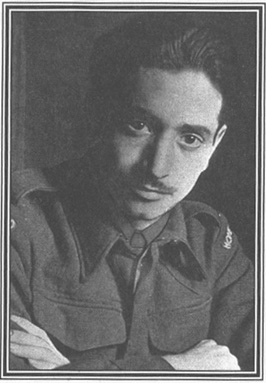

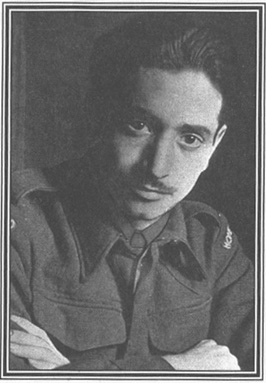

, the authors father, left Palestine for Britain in the 1930s and made a career in the West when he was not allowed to return to Israel.

PALESTINE

History of a Lost Nation

KARL SABBAGH

Copyright 2006 by Karl Sabbagh

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc.,

841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America

FIRST PAPERBACK EDITION

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sabbagh, Karl.

Palestine: history of a lost nation/Karl Sabbagh.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

Originally published: London: Atlantic Books, 2006.

eISBN-13: 978-1-5558-4874-3

1. Sabbagh, Karl. 2. Palestine ArabsBiography.

3. JournalistsPalestineBiography. 4. PalestineHistory

20th century. 5. Arab-Israeli conflict. I. Title.

DS125.3.S23A3 2007.

956.94dc22 2006049240

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

THE PLEA

To find me you must stop the noise:

silence the guns and the tanks,

the shouted orders

and the shouts of defiance,

screaming and weeping,

and listen.

My voice is very weak.

You must try to hear it.

You will have to come close

and pick away the tumbled stones

carefully, gently.

When you find me, lift me out,

help me to breathe;

set my broken limbs

but dont think its enough

to give me back a fragile existence.

I need food and water,

I need a home that will last,

health and hope and work to do.

I need love.

You must embrace me

and take me to your heart.

My name is Peace.

Sue Sabbagh, June 2002

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Page

The author and publishers are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce illustrations: Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; 27, Ziad Daher, Nazareth 1999; 291, Getty Images. All other images from the authors personal collection.

Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be glad to make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have helped me shape my ideas for this book by providing information and encouragement in the research and writing process, but the person whose inspiration and example have been most before me at every stage is Edward Said, the Palestinian intellectual and writer, and my dear friend. In his own writings he marshalled a huge amount of evidence of the injustices done to the Palestinians and wrote about the topic unapologetically, in spite of continual attempts to silence any presentation of the Palestinian case. I, too, am unapologetic, and I have no doubt that this book too will generate hostility from those who would prefer Palestinians to stay silent and accept their fate. Since Edwards death, his wife Mariam and his children, Wadie and Najla, have continued to be supportive of my work and I owe them thanks.

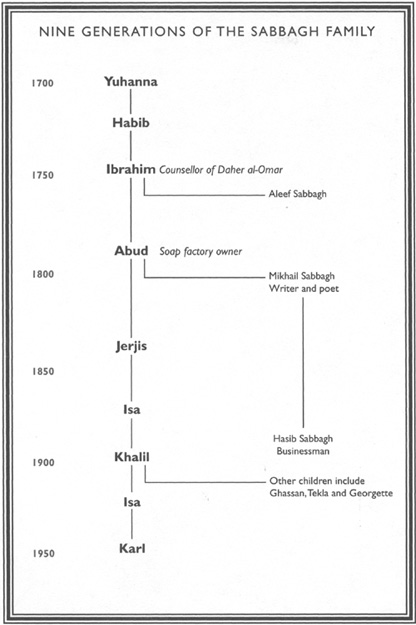

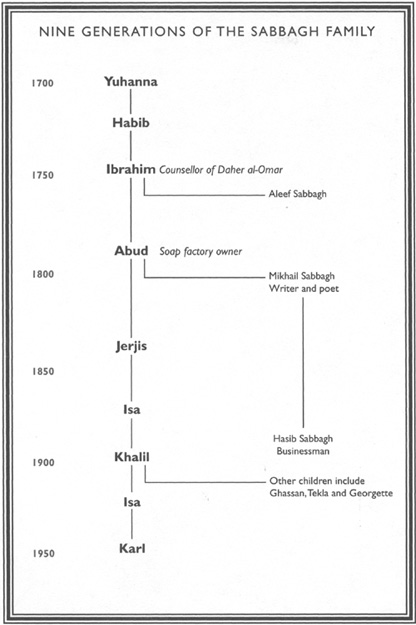

A number of members of my own family have been very helpful in sharing their memories and their comments. They include Ulla Sabbagh, Ghassan Khalil Sabbagh, Aleef Sabbagh, Hasib Sabbagh and Elias Sabbagh. It is unfortunateand a sign of the depth of fear that exists nearly sixty years after 1948that other relatives who experienced the events surrounding the expulsion of Palestinians from their homes are still reluctant to talk about it. On my mothers side of the family I am grateful to my uncle, Peter Graydon, for sharing his memories of wartime years in London.

I would like to thank a number of people who have been helpful in various ways, from reading drafts of the text and giving me their comments to supplying hospitality and information. They include Ilan Pappe, Nur Masalha, Elfi Pallis, Avi Shlaim, Afif and ChristI Safieh, Mahmoud Hawari, Raymonda Tawil and Hala Taweel, Hanna and Tania Nasir, Vera Tamari, Nadia Abu-el-Haj, Leila Tannous, Karma Nabulsi, Ghada Karmi, Diana Allan, Sasha Hoffman, Tim Rothermel, Iain Chalmers, Philip Davies, Diana Allen, Fergus Bordewich, and Duaibis and Maha Abboud Ashkar.

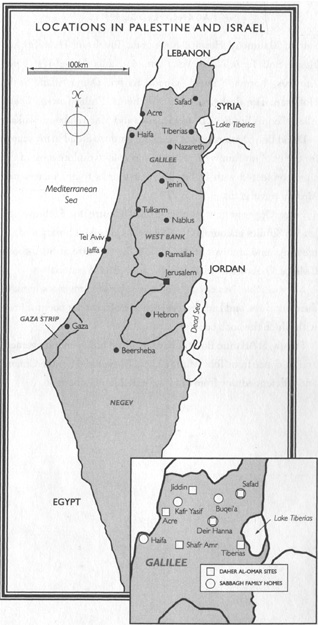

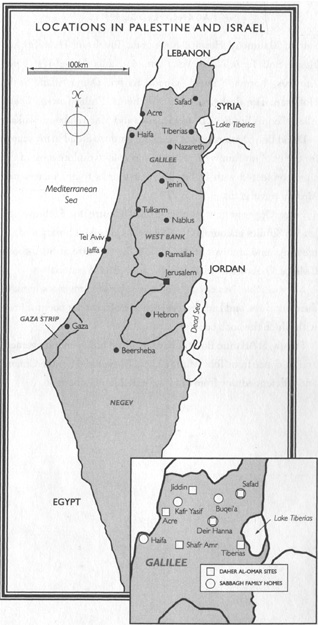

was an excellent guide to Safad in my search for traces of my family there, and I was able to explore most of the sites connected with Daher al-Omar thanks to an Ancient and Modern travel grant.

Peter Oppenheimer at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies encouraged me to use his excellent library, and the meetings and archives at the Middle East Centre at St Antonys College, Oxford, provided valuable background material.

My wife, Sue, has encouraged and supported my work in many different ways, and I am grateful in particular for her poem of hope with which the book begins.

Finally, at Atlantic Books I have received much encouragement and guidance from Toby Mundy, Clara Farmer and Bonnie Chiang, and efficient editing from Ian Pindar and Jane Robertson.

PROLOGUE

I am the son of a Palestinian father, but I am endowed with few of the characteristics associated in the popular mind with Palestinians or Arabs. I am not poor, unshaven or a speaker of broken English. I do not know how to use a gun or manufacture a bomb. I have had little to do with camels, sand or palm trees. But I both sympathize and identify with the Palestinian people. Interestingly, the sympathy was formed in my early years when I knew little about my own family connections with Palestine, raised as I was by an English mother in south London. But I could read about history and about the way in which a group of Jews called Zionists set themselves the task of turning an Arab country into a Jewish homeland, against the will of the majority of the inhabitants who had themselves been promised independence and self-government after the First World War.

A few years ago I came across an article by Freya Stark, traveller in the Middle East, published in The Times in 1940. It was headed Wireless in Arabia and described a scene in a village square on the Arabian peninsula, as the inhabitants sat around listening to Arabic music on the radio:

The square, though subdued, is full of listening ears, but it is the power of these pastoral melodies that they carry their own loneliness with them and bring into their notes the quiet horizons, the long days of sea-faring on mountain pastures, the empty, easy hours of noonday when they were first conceived. It is pleasant to have this calm contrasting picture to the European news. This now comes, dropping slowly in tempered accents: we are lucky to have an announcer with a beautiful voice. He picks out every syllable, giving it full value in a way that Arabs, who all adore their language, appreciate and understand

Next page