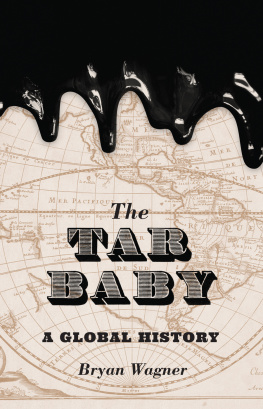

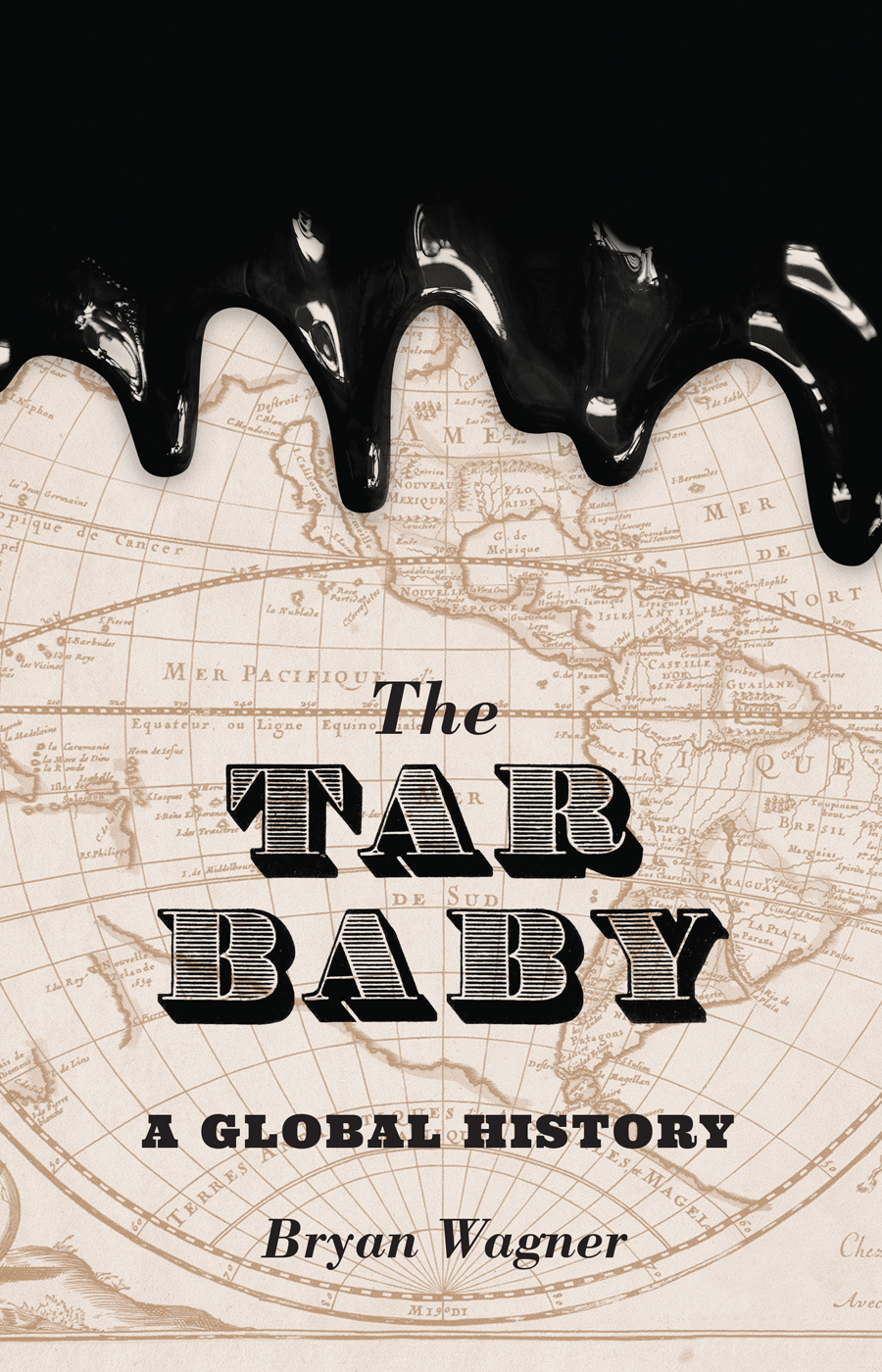

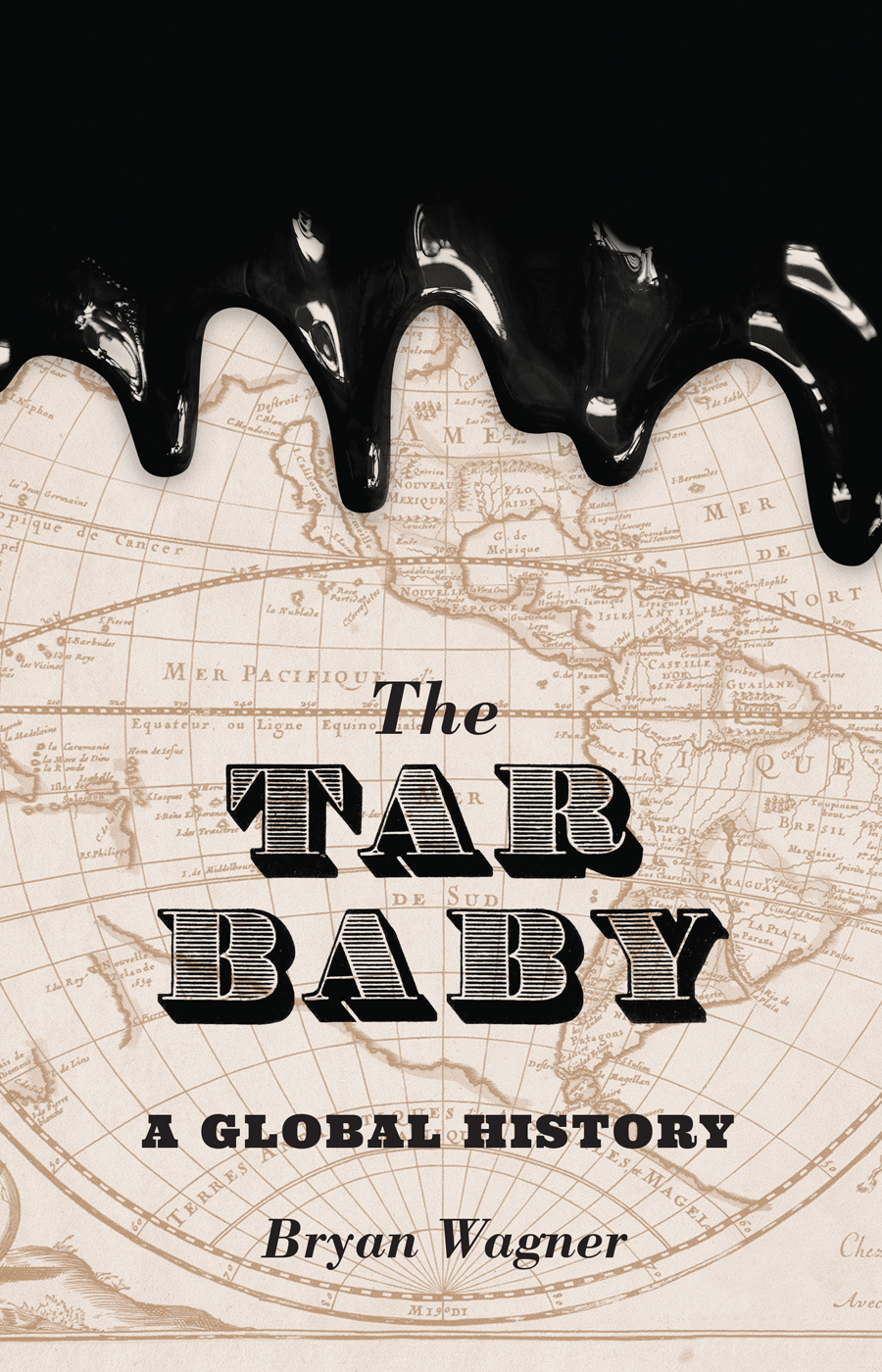

The Tar Baby

The

Tar Baby

A GLOBAL HISTORY

Bryan Wagner

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: 1) Planisphre, ou carte gnrale du monde (1676)

by Pierre Duval, Bibliothque nationale de France,

2) Type courtesy of Patricia M. / Flickr,

3) Black paint Angela Waye / Shutterstock

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17263-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016945502

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Bodoni Std, Ultra and

Adobe Garamond Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

ForNORA&CAMILLE

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

The tar baby is an electric figure in contemporary culture. As a racial epithet, a folk archetype, an existential symbol, and an artifact of mass culture, the term tar baby stokes controversy, in the first place because of its racism. At least since the 1840s, tar baby has been used as a grotesque term of abuse, and it continues to feel like an assault no matter the circumstances in which it is employed. At the same time, tar baby has operated as a figure of speech suggesting a problem that gets worse the harder you try to solve it. The term takes both of these senses in the tar baby story, a short fable that was common in vernacular tradition before it was reproduced on the gilt-edged pages of illustrated childrens books and on the silver screen.

By far the best-known version of the tar baby story is the one published by Joel Chandler Harris in his inaugural folklore collection, Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings (1881). This was not the tar babys first appearance in print, as other versions anticipated Uncle Remus by more than a decade, but it was The Wonderful Tar-Baby Story, told in the manufactured voice of an imaginary ex-slave, that made the difference to the storys future transmission, documentation, and reception. Again and again, Uncle Remuss version of the tar baby was syndicated, translated, adapted, illustrated, excerpted, and interpolated in newspapers, magazines, folklore anthologies, and childrens treasuries, as it was also repurposed in comic strips and advertising campaigns

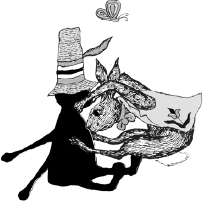

FIG. 0.1. Edward Gorey, [Rabbit Stuck to Tar Baby]. Colored pen and ink. From Ennis Rees, Brer Rabbit and His Tricks, with Drawings by Edward Gorey, (New York: Young Scott Books). By permission of the Edward Gorey Estate.

FIG. 0.2. J. M. Conde, I wish, said the little boy, I wish I could fly. Pen and ink. From Joel Chandler Harris, Uncle Remus and the Little Boy (Boston: Small Maynard and Company, 1910), 12.

The tar baby has been central to our understanding of cultural traditions that slaves brought from Africa to America. According to Herskovits, the tar baby was the keypoint in the debate over the nature and composition of black culture. The storys significance was magnified over time as it was cited as evidence against the views of sociologists such as E. Franklin Frazier, who argued that slaves retained little more than scraps of memories from the African past. The story was also invoked in arguments against Stanley Elkins, a historian who claimed that slavery destroyed the personalities of its victims, rendering them passive in the face of their oppression. As a counterexample to these claims, the tar baby showed that slaves were neither deracinated nor submissive. It was a story that survived the brutality of the Middle Passage, a story that was passed down from generation to generation and continent to continent, demonstrating the independence that

One of the problems with this conventional approach to the tar baby is a matter of evidence. Scholars have attempted to determine the origin and chart the trajectory of the tar baby as a basis for interpreting the storys meaning. This approach treats the storys worldwide diffusion as something that can be measured, and thereby used as evidence, when in fact it is something that we can never know for sure. Oral traditions do not leave dated traces, which means it is impossible to reconstruct a storys movement based on the mere fact of its existence in more than one place. All we can say for sure is that the story was told in these places. How it arrived, and where it originated, are matters for speculation. Given the available evidence, which is unreliable and inconclusive, it comes as no surprise that the tar babys diffusion has been subject to open-ended and acrimonious debate. If we want to interpret the tar baby in political terms, we need to reckon with the fact that the shape of its diffusion is not only unknown but likely unknowable. It provides no foundation for a theory of politics.

First and foremost, this empirical problem returns us to the task of interpreting the tar baby, a task that had been suspended by some of its most astute commentators, who tried to make their objective knowledge of the storys circulation into the basis for a theory of politics. Critics have worked out the metaphysical problems of political agency posed in the tar baby by invoking the storys mercurial transmission as evidence for the cultural autonomy of its storytellers, but in my view, the theory of politics generated by this critical approach remains inadequate to the storys complex meditation on the problems of action, identification, and consciousness. We have put the right questions to the tar baby, in other words, but our answers have been insufficient.

This book aspires to be more comprehensive than previous accounts of the tar baby, looking beyond oral tradition to discover examples of the storys narrative elements outside the domain claimed by folklorists. We know that the tar baby was circulating at the same time, and in many of the same places, as the new thinking about property and sovereignty that developed in colonial law and political economy. One of the purposes of this book is to demonstrate that the story addresses many of the same problemslabor and value, enclosure and settlement, crime and captivityrepresented in the tracts and charters conventionally associated with the so-called great transformation in world his-tory. Interpreted in this broader comparative context, the tar baby looks less like an ethnographic example and more like a universal history that seeks to grasp all at once the interlocking processes by which custom was criminalized, lands were colonized, slaves were captured, and labor was bought and sold, even as it also meditates on the feeling of disenchantment and the impact of science on the conflict over natural resources. We should understand the tar baby, in other words, not only as an artifact of globalization but also as an account of globalization whose scale of reference matches the scale of its diffusion.

This book departs from previous thinking about the tar baby, but it relies on critical precedents established as the story was taken up by various disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. For the purposes of this study, I have been willing to engage with any example previously seen as a version of the tar baby story. I am especially interested in versions collected and

Next page