Table of Contents

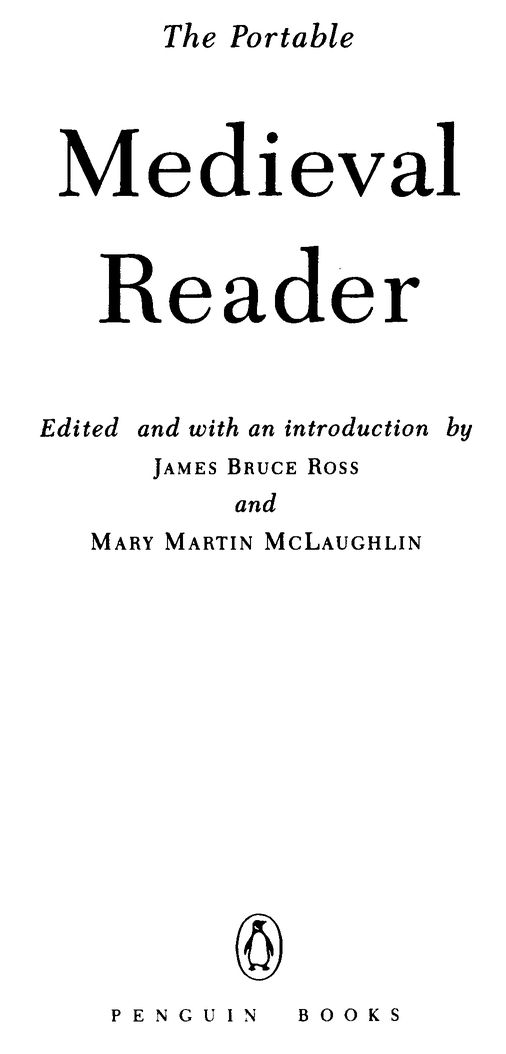

THE VIKING PORTABLE LIBRARY

Medieval Reader

James Bruce Ross was professor of medieval and Renaissance history at Vassar College for many years. She is the author of studies of medieval Flanders and Renaissance Venice, including a translation of The Murder of Charles the Good by Galbert of Bruges.

Mary Martin McLaughlin is a medievalist and independent scholar, with special interests in the history of medieval women. She has written on various other subjects, including the medieval University of Paris, the history of childhood, and Heloise and Abelard.

James Bruce Ross and Mary Martin McLaughlin also co-edited The Portable Renaissance Reader.

Each volume in The Viking Portable Library either presents a representative selection from the works of a single outstanding writer or offers a comprehensive anthology on a special subject. Averaging 700 pages in length and designed for compactness and readability, these books fill a need not met by other compilations. All are edited by distinguished authorities, who have written introductory essays and included much other helpful material.

Introduction

I

ENTERING the lists in the enduring controversy between past and present, between ancients and moderns, Walter Map, a twelfth-century writer, complained that the illustrious deeds of modem men of might are little valued, and the castaway odds and ends of antiquity are exalted. In similar vein, a scientist of the same century, Adelard of Bath, deplored the domination of the present by the past, accusing his own generation of thinking nothing discovered by modems worthy of acceptance.

But Adelards contemporary, Bernard of Chartres, called the most copious fount of letters in Gaul in modern times, said of the relationship of his age with its ancient past, We are like dwarfs seated on the shoulders of giants; we see more things than the ancients and things more distant, but this is due neither to the sharpness of our own sight nor the greatness of our own stature, but because we are raised and borne aloft on that giant mass.

Yet, whatever their differences of perspective on the past, whether they resisted the authority of the ancients, or paid admiring tribute to their greatness, these men of the twelfth century were profoundly aware of living ties with the past. In fact, they, and their predecessors and successors as well, were confronted with the problem of the past in a particularly acute form. For theirs was the task of recovering and assimilating a vast cultural legacy from pagan antiquity and of reconciling it with the Christian revelation and way of life. Although they were by no means deficient in pride in their own achievement, the weight of their debt to the past often lay heavily on them.

In our modern times, we seldom have occasion to lament the hold of the past on the present, and we rarely feel dwarfed by its greatness. We are not often inclined to take a humble view of our own stature or to acknowledge a close kinship with the past, especially with the age represented by these men of the twelfth century. As Americans, we are separated by geography from the physical environment and many of the tangible evidences of this phase of the past, and by our truncated national history from the long middle age of Western culture which is as truly ours as it is that of European peoples. We are often still further divorced from our remoter history by a grandiose conception of progress in which our own role looms large and that of the future larger still. This orientation is a common one, although the optimistic theory on which it rests has grown somewhat threadbare in an age when human advancement appears more and more as a slow crablike movement sideways.

Yet there is much evidence today of a haunting awareness of failure, of dissatisfaction with modern perspectives, of an anxious pursuit of enlightenment in the sources of our culture. We are increasingly conscious of the fact that while in a sense history, as Voltaire cynically put it, is a pack of tricks the living play upon the dead, it is also a pack of tricks that the dead have played on us. We are pathetically eager to consult the past, as we might a psychiatrist, to discover when and where things went wrong, to probe for the roots of modern neuroses. Seeking to comprehend the meaning of our own experience, and to restore a sense of continuity with the past, we read the great books, we take courses in contemporary civilization and its background, we pore over complex works of historical interpretation. All this is surely a healthy sign that, whether we regard the past as a burden or as a legacy, we recognize that our ties with it are inseverable, and that we may possibly profit from its experience.

But perhaps, even in these efforts, we view the past too much through the distorting lenses of the present. Great books and lesser ones, too, have great value, but really to be understood they must be read in the context of their own times. Probably no age can fully escape bondage to present-mindedness; when it looks into the mirror of the past, it sees, like Narcissus, its own image. Yet, in order to see ourselves at all clearly in the mirror of a different age, we must try to understand that age in its own terms, we must attempt to relive its experience and to rethink its thoughts. By transcending the limitations of the present, we may extend our experience in time and space, and perhaps come to know ourselves better.

The middle ages of Europe were the spawning ground of the modern Western world. In the teeming life of the medieval centuries many aspects of modern societyits nation-states, its institutions, its class structure, its urban way of lifeexisted in embryo or in more advanced stages of development. But medieval culture was complete and distinctive in itself. Although this culture and its modem descendant have much in common, they also differ profoundly and often in the most striking ways. Emphasis on the differences, rather than on the similarities, between medieval thought and experience and our own has often encouraged the feeling that this is a dead past, with no significance for the present. Yet no area of the past is dead if we are alive to it. The variety, the complexity, the sheer humanity of the middle ages live most meaningfully in their own authentic voices, for as Walter Map said of the ancients, their diligent achievement is in our possession; they make their own past present to our times. Not only in their great books, in the works of their extraordinary men, is the medieval achievement still vital, but also in the records of the lives and work, the pleasures, sufferings, and strivings of their ordinary people.

The aim of the Portable Medieval Reader is to provide, by means of selections from these sources, a little mirror of the middle ages in which medieval men and women may appear as they saw themselves and in which we may see the evidences of our kinship with them. Perhaps it may also fulfill the expectations of the medieval writer who said, I believe that in future times there will be men, like myself, who will eagerly search the pages of historians for the acts of this generation, that they may be able to disclose occurrences which have taken place in past ages for the instruction and amusement of their contemporaries.

II

If it is true that the middle ages are significant for us both as a distinct culture and as the ancestral form of our own, why does this period often seem dim and alien and in some way sharply cut off from our own? How did the concept of a middle age develop, and how has the term medieval acquired its rather vague and derogatory connotations of dark and barbarous? Medieval men like Walter Map and Adelard of Bath clearly thought of themselves as modern in relation to the ancients. Perhaps the arbitrary divisions and conventional characterizations of history do not represent eternal verity, but rather the special interests or the blind spots or the arrogance of different ages. The kind of thinking which tries to confine the unwieldy and intractable past in neat pigeonholes is one of those tricks which the living of one age play on the dead of another. It tends to exalt those periods with which a particular age may identify itself more closely and to pass over those which for one reason or another are less agreeable.