WAR COLLECTIVISM

Power, Business, and the Intellectual Class

in World War I

WAR COLLECTIVISM

Power, Business, and the

Intellectual Class in World War I

Murray N. Rothbard

MISES

INSTITUTE

AUBURN, ALABAMA

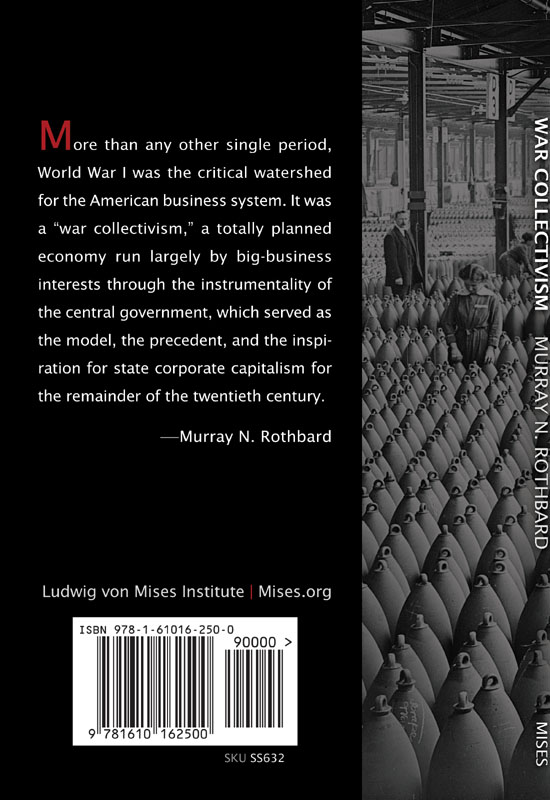

Cover photo copyright Imperial War Museum. Photograph by Nicholls Horace of Munition workers in a shell warehouse at National Shell Filling Factory No.6, Chilwell, Nottinghamshire in 1917.

Copyright 2012 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is gladly granted, provided full credit is given.

Ludwig von Mises Institute

518 West Magnolia Avenue

Auburn, Alabama 36832

mises.org

ISBN: 978-1-61016-250-0

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Economics in Service of the State:

The Empiricism of Richard T. Ely

Economics in Service of the State:

Government and Statistics

I

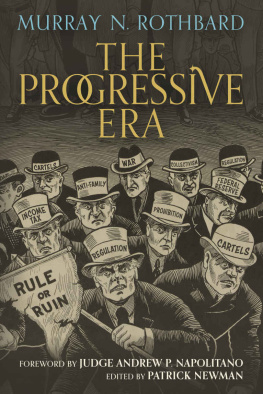

War Collectivism in World War I

M ore than any other single period, World War I was the critical watershed for the American business system. It was a war collectivism, a totally planned economy run largely by big-business interests through the instrumentality of the central government, which served as the model, the precedent, and the inspiration for state corporate capitalism for the remainder of the twentieth century.

That inspiration and precedent emerged not only in the United States, but also in the war economies of the major combatants of World War I. War collectivism showed the big-business interests of the Western world that it was possible to shift radically from the previous, largely free-market, capitalism to a new order marked by strong government, and extensive and pervasive government intervention and planning, for the purpose of providing a network of subsidies and monopolistic privileges to business, and especially to large business, interests. In particular, the economy could be cartelized under the aegis of government, with prices raised and production fixed and restricted, in the classic pattern of monopoly; and military and other government contracts could be channeled into the hands of favored corporate producers. Labor, which had been becoming increasingly rambunctious, could be tamed and bridled into the service of this new, state monopoly-capitalist order, through the device of promoting a suitably cooperative trade unionism, and by bringing the willing union leaders into the planning system as junior partners.

In many ways, the new order was a striking reversion to old-fashioned mercantilism, with its aggressive imperialism and nationalism, its pervasive militarism, and its giant network of subsidies and monopolistic privileges to large business interests. In its twentieth-century form, of course, the New Mercantilism was industrial rather than mercantile, since the industrial revolution had intervened to make manufacturing and industry the dominant economic form. But there was a more significant difference in the New Mercantilism. The original mercantilism had been brutally frank in its class rule, and in its scorn for the average worker and consumer. Instead, the new dispensation cloaked the new form of rule in the guise of promotion of the overall national interest, of the welfare of the workers through the new representation for labor, and of the common good of all citizens. Hence the importance, for providing a much-needed popular legitimacy and support, of the new ideology of twentieth-century liberalism, which sanctioned and glorified the new order. In contrast to the older laissez-faire liberalism of the previous century, the new liberalism gained popular sanction for the new system by proclaiming that it differed radically from the old, exploitative mercantilism in its advancement of the welfare of the whole society. And in return for this ideological buttressing by the new corporate liberals, the new system furnished the liberals the prestige, the income, and the power that came with posts for the concrete, detailed planning of the system as well as for ideological propaganda on its behalf.

For their part, the liberal intellectuals acquired not only prestige and a modicum of power in the new order, they also achieved the satisfaction of believing that this new system of government intervention was able to transcend the weaknesses and the social conflicts that they saw in the two major alternatives: laissez-faire capitalism or proletarian, Marxian socialism. The intellectuals saw the new order as bringing harmony and cooperation to all classes on behalf of the general welfare, under the aegis of big government. In the liberal view, the new order provided a middle way, a vital center for the nation, as contrasted to the divisive extremes of left and right.

I

We have no space here to dwell on the extensive role of big business and business interests in getting the United States into World War I. The extensive economic ties of the large business community with England and France, through export orders and through loans to the Allies, especially those underwritten by the politically powerful I.P. Morgan & Co. (which also served as agent to the British and French governments), allied to the boom brought about by domestic and Allied military orders, all played a leading role in bringing the United States into the war. Furthermore, virtually the entire Eastern business community supported the drive toward war.

The first organization to move toward economic mobilization for war was the Committee on Industrial Preparedness, which in 1916 grew out of the Industrial Preparedness Committee of the Naval Consulting Board, a committee of industrial consultants to the Navy dedicated to considering the ramifications of an expanding American Navy. Characteristically, the new CIP was a closely blended public-private organization, officially an arm of the federal government but financed solely by private contributions. Moreover, the industrialist members of the committee, working patriotically without fee, were thereby able to retain their private positions and incomes. Chairman of the CIP, and a dedicated enthusiast for industrial mobilization, was Howard E. Coffin, vice-president of the important Hudson Motor Co. of Detroit. Under Coffins direction, the CIP organized a national inventory of thousands of industrial

The CIP was succeeded, in late 1916, by the fully governmental Council of National Defense, whose Advisory Commissionlargely consisting of private industrialistswas to become its actual operating agency. (The Council proper consisted of several members of the Cabinet.) President Wilson announced the purpose of the CND as organizing the whole industrial mechanism... in the most effective way. Wilson found the Council particularly valuable because it opens up a new and direct channel of communication and cooperation between business and scientific men and all departments of the Government....

Exulting over the new CND, Howard Coffin wrote to the du Ponts in December, 1916, that it is our hope that we may lay the foundation for that closely knit structure, industrial, civil and military, which every thinking American has come to realize is vital to the future life of this country, in peace and in commerce, no less than in possible war.