The author wishes to thank the following for their help in the research for this book:

George C. Bean, Thomas R. Bowerman, Mike Buckingham, C. Bernard Covington, Richard Elvin, Leo Hogan, Albert Kelder, Charles A. Lloyd, Arthur MacLaren, Ian A. Millar, Frits Noorbergen, Peter L. Price, Mike Raymond, Barbara Reher, Neil Staples, Tony Thomas, Barry L. Zerby, and Flower Class Corvette Association, Merchant Navy Association, National Archives & Records Administration, National Headquarters American Merchant Marine Veterans, Public Record Office, Registry of Shipping & Seamen, US Armed Guard WW II Veterans.

Introduction

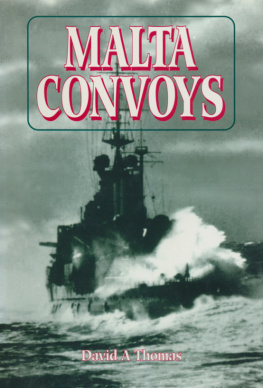

This is the story of a very gallant company of men, who in the dark days of 1942 brought their ships through to Russia by the Arctic route. They were drawn from a dozen diverse nations, but united by a common cause; to bring aid to a beleaguered ally. If by doing so they helped to change the fortunes of a war, then being dictated by the crushing superiority of the Axis Powers, they considered their work well done.

In a single voyage, the men who sailed the convoys to North Russia faced more dangers than many others faced in six years of war. Their age-old enemy, the weather, was relentless. It fluctuated from violent storms that threatened to swamp the grossly overloaded merchantmen and crush the thin-hulled escorts, to flat calms and dense fogs. Caught in fog, the ships, unable to stand still, were forced to steam blind, under constant threat of collision with each other and ever watchful for the silent approach of icebergs and growlers, some big enough to rip their bottoms open from stem to stern.

If the weather was overcome or at least held at bay there was still the other enemy to contend with. He, too, was relentless, attacking from the air with high-level bombers, dive-bombers and torpedo bombers, on the surface with fast, powerful warships, and from beneath the sea with the shadowing U-boat.

For much of the year, overlaying and aggravating all these dangers, was the awful, bone-chilling cold of the Arctic; a cold so intense that it immobilized the body and numbed the brain. Death followed within two minutes for any man entering the water, and those who found themselves adrift in open boats were promised a slow death by exposure or, at the very least, the pain and indignities of frostbite and immersion foot, which so often led to the horrors of amputation.

For those who won through to Russia against such fearful odds, there was no safe haven at the end. The German bombers followed them into port, and continued to rain down death and destruction as they struggled to discharge the guns and tanks they had so diligently carried across the sea. All too often, their efforts were brought to nothing as ship and cargo were blown asunder or consumed by fire. But perhaps the most bitter blow they had to take was the rejection by the people they had endured so much to help. The ordinary Russian citizen was too cowed by authority to openly fraternize, and Soviet officialdom regarded them as agents of the hated capitalist system, and put every possible obstacle in their way.

The sea road to Russia was long and fraught with many dangers and frustrations, but these men did not hesitate to tread it, not just once, but voyage after voyage. They were true heroes.

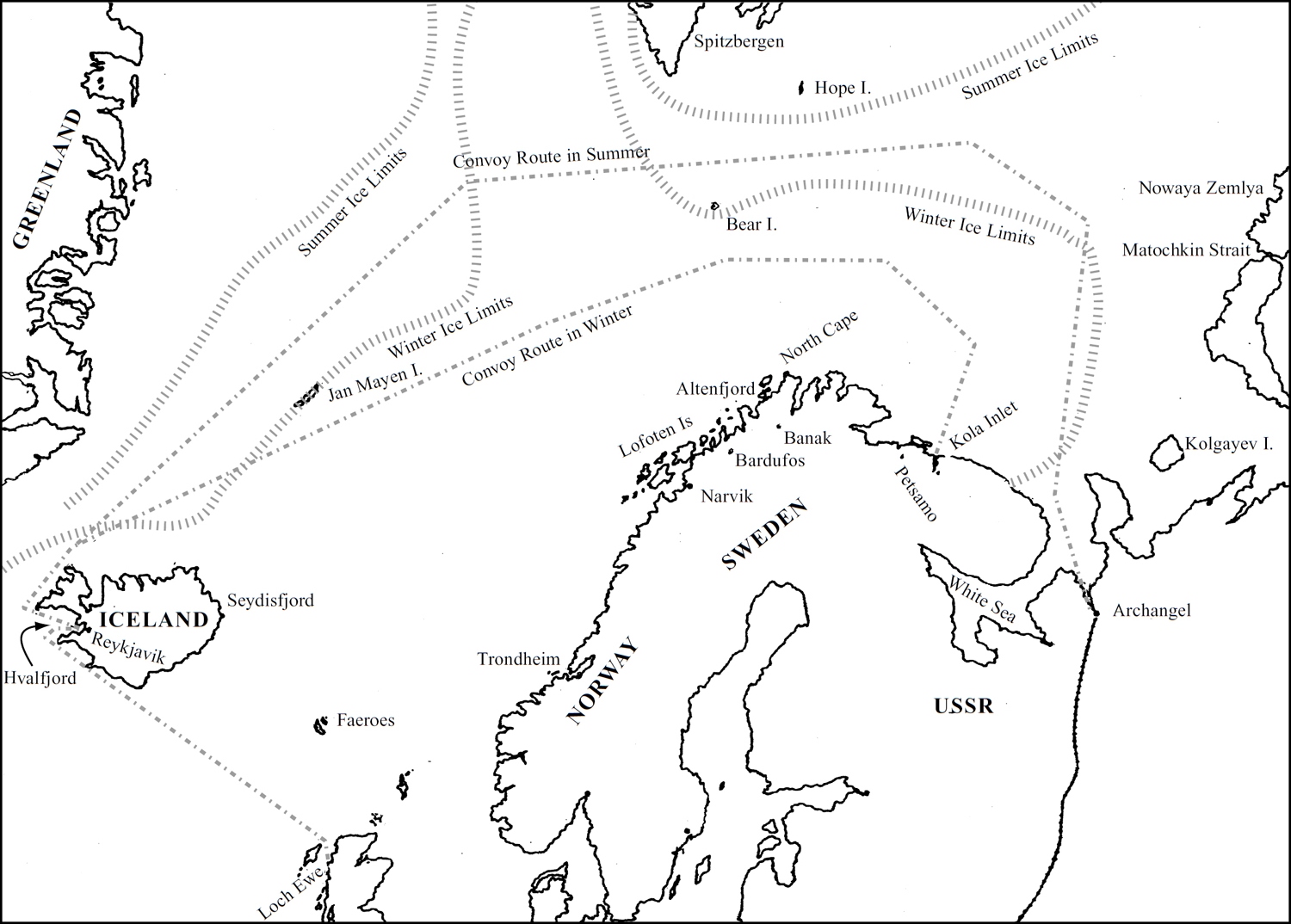

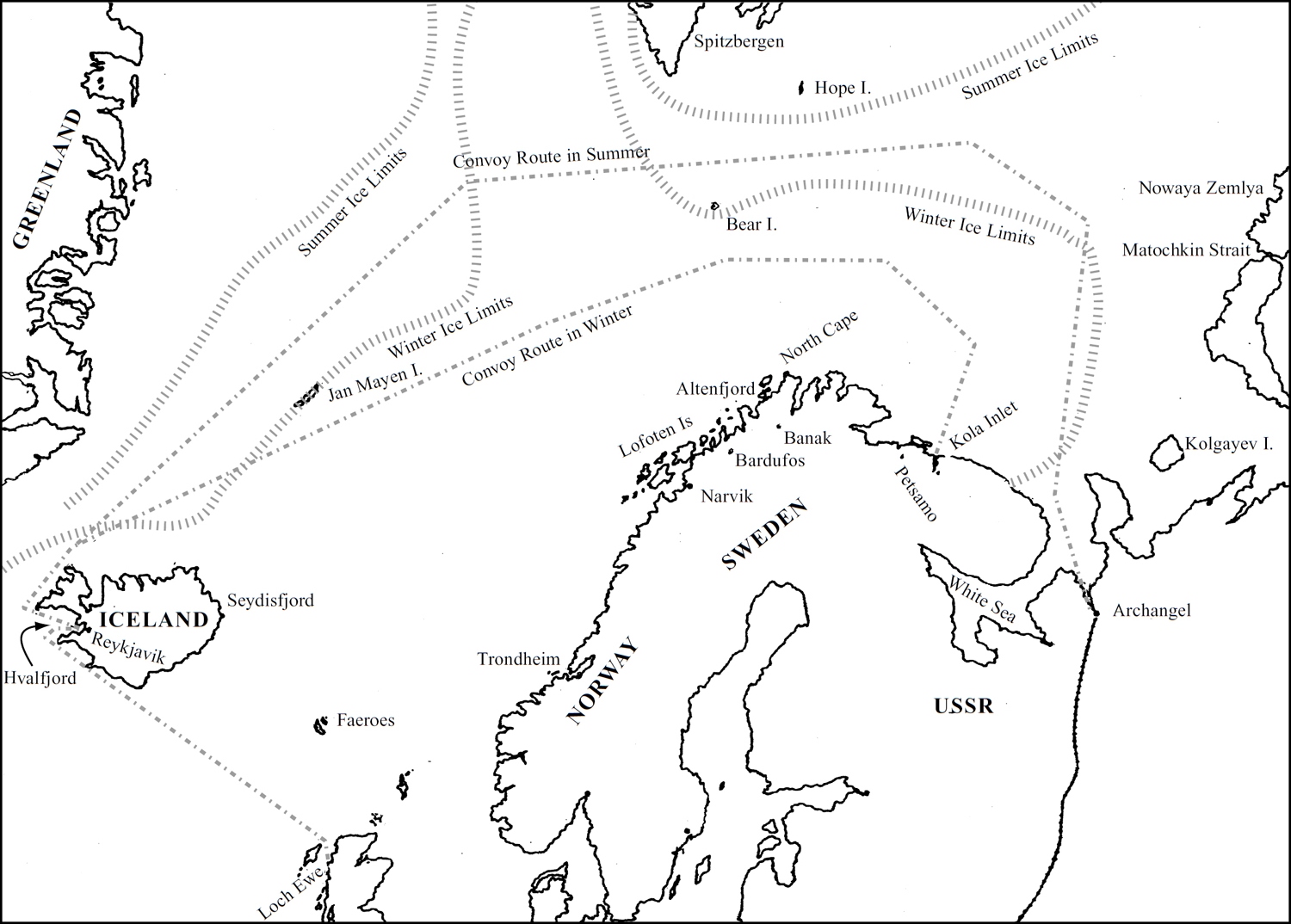

Chapter One

In 1942, when war raged unchecked over half the world, there was no supply line more bitterly contested than the 2000-milelong sea road through Arctic waters to Russia. Sometimes likened to the road to hell itself, it was paved with good intentions, but littered with the wreckage of sunken ships and the frozen bodies of those who had fallen on the way. The British steamer Harmatris , commanded by Captain R.W. Brundle, was one of its first victims.

Owned by J.&C. Harrison of London, the 5395-ton Harmatris sailed from Glasgow on 27 November 1941, bound for Archangel, via Iceland, with a cargo of 8000 tons of military supplies. Her voyage became a test of endurance and courage for her crew from the outset. Within twenty-four hours of reaching Reykjavik, she ran into the most atrocious weather and, battered by storm-force winds and mountainous seas, was forced to heave to. This was neither a new experience, nor a serious threat to the Harmatris . She was a strong, Clyde-built ship, and had served her time in the North Atlantic, but she was sorely tested when, late on the night of 6 December, fire broke out in the cargo. Not unexpectedly, her cargo on this current voyage included a large quantity of small-arms ammunition enough to blow the ship and all those who sailed in her to oblivion.

Run-of-the-mill merchant ships do not carry much in the way of firefighting equipment, nor do they, when at sea, enjoy the luxury of being able to call on the services of the local fire brigade. In a cargo ship, then, an outbreak of fire when away from the land can be a desperate business. But, led by forty-seven-year-old Captain Brundle, the crew of the Harmatris , with one hand for the ship, and one hand for themselves as she pitched and heaved in the mountainous seas, fought a two-day battle with hoses, eventually subduing, and then extinguishing the blaze. When it was safe to do so, the hatches were opened up and it was found that, in addition to the damage caused by the fire, heavy military vehicles had broken adrift with the violent motion of the ship. They had then run amok, reducing the other cargo around them to a broken shambles. Quite clearly, the Harmatris was in no fit condition to continue her voyage to Russia. Brundle decided to return to Glasgow.

The old saying, It is an ill wind that blows nobody any good, is often challenged, but in this case the crew of the Harmatris were beneficiaries. The repairs to the ship and the replacement of her damaged cargo turned out to be a slow operation, with the result that Christmas 1941 was spent in Glasgow docks, an unexpected and very welcome surprise that went a long way towards compensating for the horrors of the failed attempt to reach Iceland.

The ship and her cargo made good, her crew refreshed, Harmatris sailed from the Clyde again on 26 December with Convoy PQ 8. The convoy consisted of only eight merchantmen, of which Captain Brundle, being the most experienced master, was appointed Commodore. His role, in addition to commanding his own ship, was to organize and lead the other ships and liaise with the Senior Officer Escort (SOE). Reykjavik was reached on New Years Day 1942, and the convoy sailed again on 8 January, bound for Murmansk. Strong winds and rough seas were experienced for the first three days, then the ships ran into heavy field ice. It seemed that this was going to be another miserable passage for the Harmatris . Then, as it so often does in Arctic waters, the weather relented, giving way to light, variable winds, calm seas, and maximum visibility.