MALTA CONVOYS

David A. Thomas has also written:

Naval History

WITH ENSIGNS FLYING

SUBMARINE VICTORY

BATTLE OF THE JAVA SEA

CRETE 1941: THE BATTLE AT SEA

JAPANS WAR AT SEA: PEARL HARBOUR TO THE

CORAL SEA

ROYAL ADMIRALS

A COMPANION TO THE ROYAL NAVY

THE ILLUSTRATED ARMADA HANDBOOK

THE ATLANTIC STAR 193945

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS: MASTER OF THE

ATLANTIC

QUEEN MARY AND THE CRUISER: THE CURACOA

DISASTER

(With Patrick Holmes)

BATTLES AND HONOURS OF THE ROYAL NAVY

Social History

THE CANNING STORY 17851985

CHURCHILL: THE MEMBER FOR WOODFORD

Bibliography

COMPTON MACKENZIE: A BIBLIOGRAPHY

(with Joyce Thomas)

Juvenile

HOW SHIPS ARE MADE

Malta Convoys

DAVID A. THOMAS

First published in Great Britain 1999 by

Leo Cooper

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books

47, Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS.

Copyright 1999 David A. Thomas

ISBN 0 85052 6639

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Typeset in 11/13pt Sabon by

Phoenix Typesetting, Ilkley, West Yorkshire

Printed by Redwood Books Limited, Trowbridge, Wilts.

CONTENTS

Admiral of the Fleet Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope KT GCB OM DSO** was known less grandly and more affectionately throughout the fleet by his initials ABC Andrew Browne Cunningham. He was admired, respected, feared and acknowledged by historians to be the greatest naval commander at sea since Nelson. He was a master strategist and his campaign as Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean for two and a half years (193942) will be studied with admiration by generations of naval officers throughout the world.

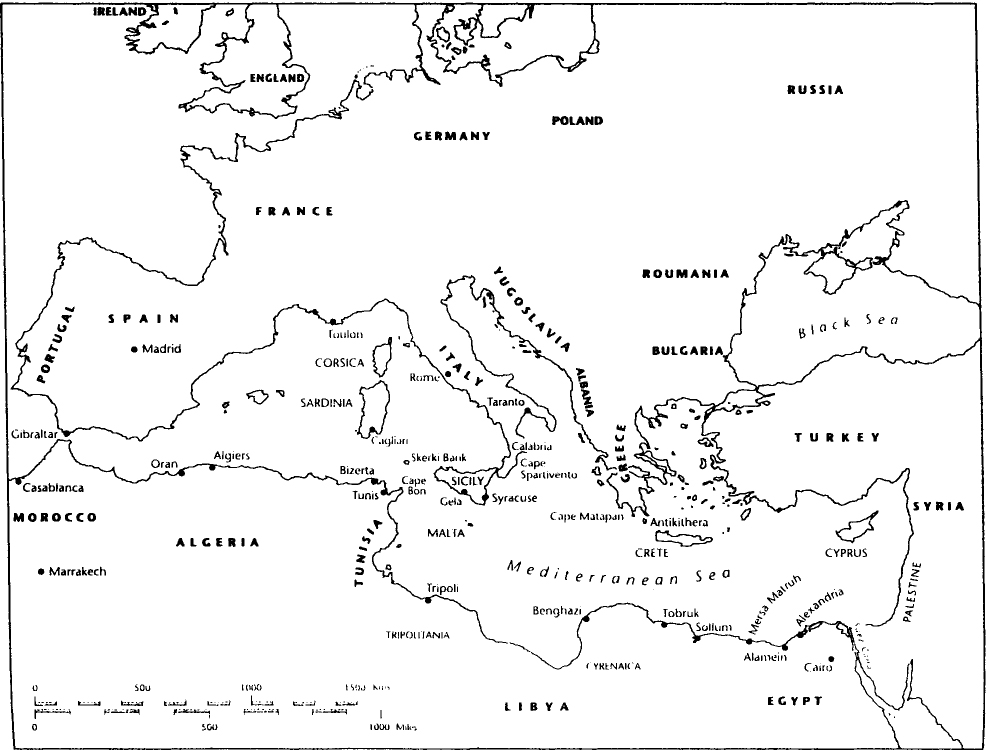

His period of command in the Mediterranean was marked by thunderous and bloody air/sea battles and clashes at sea now legendary: Matapan, Taranto, the Crete campaign, the convoy battles of Operations Collar, Tiger, Substance, Halberd, Harpoon, Vigorous and Pedestal, the battles of Sirte, Calabria and Spartivento. He commanded the submarine flotillas operating from Malta with no geographical location to honour their gallantry. He also commanded all the actions of Admiral Sir James Somervilles Force H and the strikes of Force K. It was an anxious period, an endless story of heavy losses of naval vessels including splendid ships like Barham, Ark Royal, Eagle, Manchester, Fiji, Gloucester, Neptune, Cairo, Hermione, Southampton and Welshman, apart from all the smaller ships.

Heaviest losses in terms of personnel occurred aboard the ponderous 31,100-ton bulk of the battleship Barham (8 15" guns). She was torpedoed off Solium by U-331 and exploded with dreadful loss of life.

Ark Royal (22,000 tons and 72 aircraft) was another loss, but, by contrast, suffered virtually no casualties when torpedoed by U-81. The carrier was taken in tow, but could not be salved, although nearly in sight of Gibraltar.

Eagle (10,800 tons and 15 aircraft) was another casualty when torpedoed and sunk by U-73 off Algiers.

The cruiser Gloucester (9,400 tons and 12 6" guns) was just one of several cruisers bombed to destruction by skilled German and Italian dive bombers off Crete. On the very same day the cruiser Fiji (8,000 tons and 12 6" guns) was shattered by bombs from the same squadron of bombers. Cairo (4,290 tons and 8 4 " guns), a small AA cruiser, also succumbed to the Luftwaffe pilots.

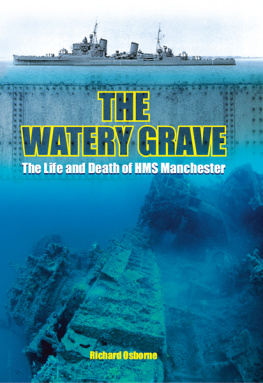

Cruisers seemed particularly vulnerable to air attacks. The 10,000-ton Manchester (12 6" guns) was attacked and torpedoed by two torpedo boats, MAS 16 and MAS 22, off Tunisia in the Operation Pedestal convoy battle. Southampton (9,400 tons and 12 6" guns) was bombed by German aircraft in January, 1941. Efforts to save her failed and she was scuttled the following day.

HMS Hermione (5,450 tons and 10 5.25" guns), a modern cruiser, barely a year old, was torpedoed by U-205 in a hard-fought battle in June, 1942.

Yet another U-boat success was the sinking of the minelayer HMS Welshman by U-617 a few days after the relief of Malta. The U-boats commander, Albrecht Brandi, watched the death throes of the minelayer through his periscope: he claimed two torpedo hits, saw a huge boiler explosion and the capsizing of the ship before she disappeared.

It is not without significance that most of these sinkings were achieved by German forces and not Italian. But the Italians did enjoy one spectacular success, though they were unaware of its extent. It was a crowning indignity for the Mediterranean Fleet. It came in December, 1941, when six brave Italian human torpedo-men penetrated the Alexandria defences and mined the hulls of the battleships Queen Elizabeth and Valiant (both 32,700 tons and 8 15" and 12 6" guns). Admiral Cunningham related the incident in his autobiography:

For some time we had suspected that the Italians contemplated an attack on the battleships. We had information that they possessed some sort of submersible explosive motorboat which could travel on the surface or underwater and was fitted with apparatus for lifting [torpedo] nets which enabled it to pass under the normal defences. On 18 December I warned the fleet by signal that attacks on Alexandria harbour by air, boat or human torpedo might be expected in calm weather. Besides the boom and net defence at the harbour entrance, each battleship was surrounded by a floating net as a protection against torpedoes whether human or otherwise. Furthermore patrolling boats dropped small explosive charges at the harbour entrance.

On 19 December at about 4 am the C-in-C was called from his cabin aboard the Queen Elizabeth to be told that two Italians had been found clinging to Valiants bow buoy. Mines had been secured to the hulls of the two battleships. Cunningham was on the quarterdeck when a violent explosion ripped open the stern of the tanker Sagona lying close to the Queen Elizabeth, with the destroyer Jervis (1,695 tons and 6 4.7" guns) lying alongside. Both were severely damaged. About twenty minutes later there was a heavy explosion under Valiants fore turret. This was quickly followed by another explosion while Cunningham was right aft by the Queen Elizabeths ensign staff. He was tossed in the air. Both battleships were badly damaged, Valiant down by the bows and the flagship with a heavy list to starboard.

However, both ships settled squarely on the bottom in shallow water, the damage disguised so as to deceive the enemy into thinking the ships were safely secured to their buoys, whereas they were both immobilized for several months. It was a severe blow to Cunningham. The navy had reached its nadir. The C-in-C commanded a phantom fleet, the majority of his destroyers, cruisers, aircraft carriers and battleships unfit for battle and no longer seaworthy. Without the navy the prospects for Maltas survival seemed grim. Abandonment of the island had always been an option and its survival or surrender came as close as the toss of a coin. Cunninghams answer, however, was for action and battle. He took every opportunity to seek out units of the Italian fleet, so that every time they put to sea they did so at their peril.

The Luftwaffe air squadrons, however, posed different problems. They were looked upon less favourably by the Royal Navy and with a healthy respect.