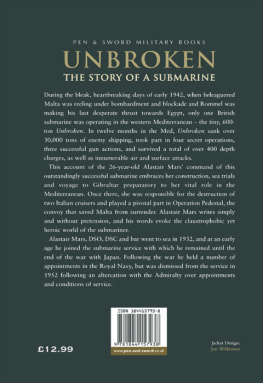

First published in Great Britain in 1957 by George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd

Reprinted in this format in 2008 by

PEN & SWORD MARITIME

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John Frayn Turner, 1957, 2008

ISBN 978 1 84415 724 2

The right of John Frayn Turner to be identified as author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by CPI Antony Rowe

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

STOP all supplies from Italy to Tripoli.

Commander G. W. G. (Shrimp) Simpson fingered the flimsy signal giving him these clear, concise instructions to intercept the enemys sea traffic in the vital mid-Mediterranean. It was January 10, 1941. Simpson had arrived to take up his duties as Commander (Submarines), Malta, and these orders came from the Commander-in-Chief of the island.

Not a submarine in sight, Simpson murmured to Geoffrey Tanner, a lieutenant-commander appointed as his staff officer of operations. Still, I suppose this is as good a time as any. Weve just got to start right from scratch. First well have to get some subs., then find out which routes the Huns are taking to the North African coast, and then theres the detail of discovering when they can be expected. Thats all! Simpson was speaking as he looked out over Lazaretto Creek, soon to be the headquarters of the Malta Force Submarines.

The war was only sixteen months old, but British policy in the Mediterranean had already suffered a succession of setbacks. The traditional aim was to keep the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal open for the Alliesand closed to the enemy. When war broke out the British and French fleets seemed strong enough to tackle this task. Then the complete collapse of France and entry of Italy into the war changed the situation suddenly. The strategy remained the same, but the method of achieving it had to be radically reconsidered and forces moved accordingly.

Malta became a card which somehow had to be played and yet held in our hand.

So withering was the Italian air superiority that the island could not be considered as a permanent base for our fleet. But it could become a staging post for convoys through the Mediterranean; and a base for air and submarine assault on the enemys sea-links with her forces in North Africa. Malta, in fact, was an offensive outpost rather than a defensive base.

Meanwhile the Mediterranean Fleetsafely based on Alexandriacould keep the Central and Eastern Mediterranean free, besides bringing valuable support to the Army of the Nile in its operations along the coastal strip of the Western Desertwith its one road between Tripoli and El Alamein.

This rapidly revised concept of the strategic requirements was justified by the events in the summer of 1940. General Wavell inflicted a thundering defeat upon the Italians; Admiral Cunninghams aggressive policy hit the Italian fleet hard, culminating in the crippling attack in Taranto harbour; and several convoys sailed successfully from one end of the Mediterranean to the other, calling at Malta en route.

All available fighter aircraft were tied up in the summer skies over England, but this deplorable lack of air power did not affect the situation as seriously as later, in 1941 and the spring of 42. The anti-aircraft defence hammered healthily away as deterrents to the high-level bombing of the Regia Aeronautica. What bombers the R.A.F. and Fleet Air Arm did possess concentrated on attacking Italian bases and convoys with bombs and torpedoes.

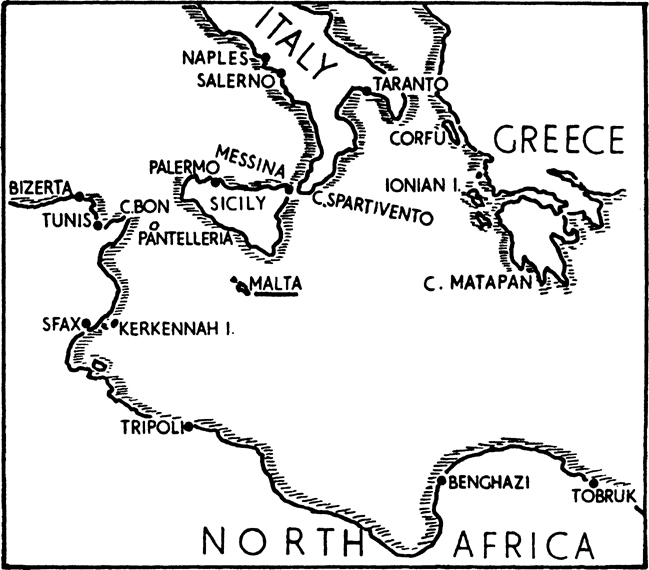

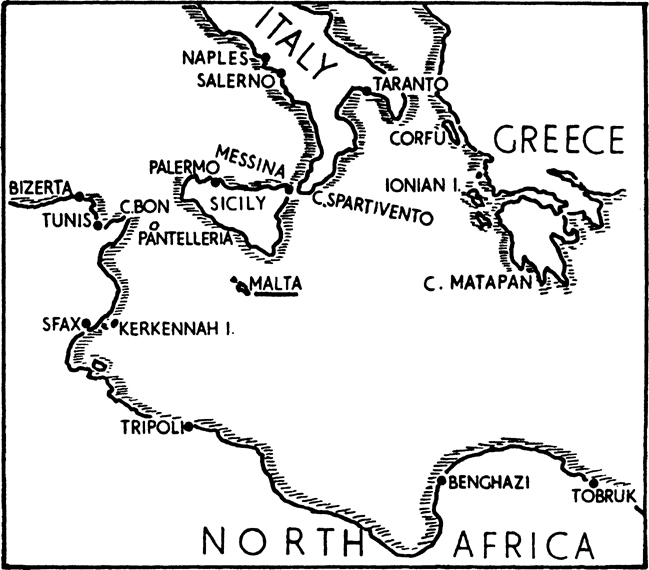

THE CENTRAL MEDITERRANEAN, WHERE 10TH SUBMARINE FLOTILLA OPERATED

With the Alexandria fleet was a flotilla of large patrol-class submarines. During 1940 one or two of these would occasionally call at Malta and carry out sorties from the island. But because of their size they could only be used in the deeper waters off Italy, whereas it was gradually realized that the decisive duels would be fought in the shallower waters of the areas around Cape Bon, Taranto, Benghazi, and Tripoli.

As the fleet was far away at Alexandria, the enemy came to concentrate his supplies on Tripoli, to avoid any risk from farther east. An air attack was kept up from Malta against this main supply route, but the small force of planes limited results. So came the historic decision to operate some of the small U-class submarines from the island. These were by then becoming available from the North Sea, where a lack of targets existed for them, and they seemed to be exactly suitable for patrollingand attackingin the shallow waters west and south of Malta.

The closing days of 1940 added another factor. Germany revealed her intention of bolstering up her Italian ally in the desert. The advance party of the Afrika Korps called for more protection than the Italians couldor wouldgive; so squadrons of Junkers dive-bombers landed in Sicily with the all too obvious aim of neutralizing Malta as a thorn in their lines of communication. The little island lay squarely between a pair of pincers whose northern arm already swung as far east as the Balkans and whose southern arm was being re-forged at Tripoli. They hinged on Sicily. And Malta stood sixty miles away.

In those distant days air reconnaissance for submarines was an unheard-of luxury. The few planes available for anything but defence were fully occupied in flying to keep the C.-in-C. constantly notified of the whereabouts and movements, if any, of the Italian battle fleet. Information from other sources was meagre at this stage. Occasionally our Secret Service might send intelligence of an African-bound convoy, but the only thing to be done reallyonce Simpson had some submarineswas to go out and find the enemy and sink them.