My third book has taken several years of research and I am indebted to a great many people in helping me, but most of all to Sally Keyes, John Mejors daughter and David Macfarlanes great-niece, who was brave enough to allow me to write her dads and her great-uncles story. I hope she feels that I have been able to tell it accurately and to do them both justice.

I have been able to use Johnnies log books and papers, together with family papers from David Macfarlane that Sally was willing to share with me.

To anyone I have inadvertently omitted, I apologise in advance.

I have interviewed several pilots who flew with Johnnie Mejor and who were also in Malta at the time of Operation Pedestal.

Before his death, I had already been in touch with Jack Rae in New Zealand, who was able to recall his time on the island, having flown into Malta from the American aircraft carrier USS Wasp as part of the same Operation Calendar as Johnnie Mejor on 20 April 1942, and in turn gave me permission to use quotes from his own book Kiwi Spitfire Ace , published by Grub Street several years ago.

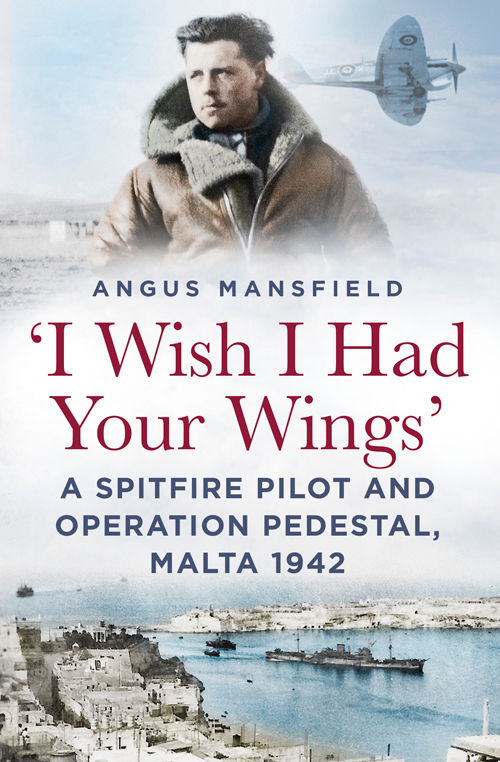

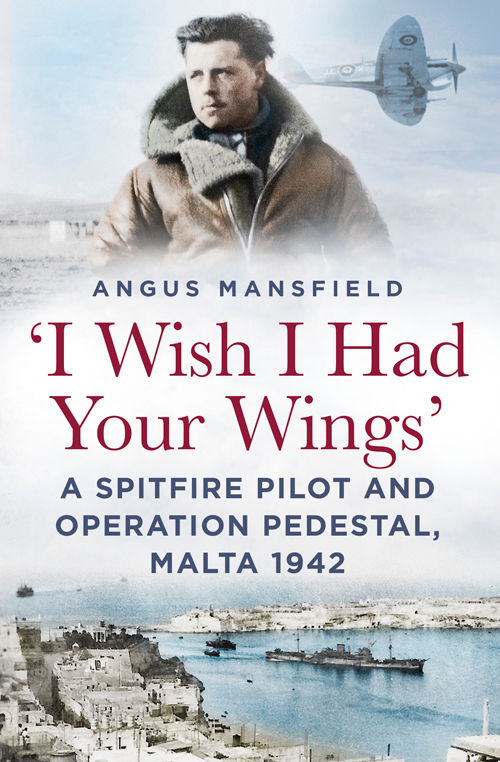

Geoffrey Wellum flew his Spitfire into Malta from HMS Furious as part of Operation Bellows and the wider Operation Pedestal on 11 August, just after HMS Eagle had been sunk. Having flown into Malta, he joined 1435 Squadron along with Johnnie Mejor. He is still alive and well and living in Cornwall, and gave me permission to use quotes from his book First Light , now a bestseller. Penguin Books were also good enough to give me permission to use the same.

Allan Scott first met Johnnie Mejor in Malta, they flew together with 1435 Squadron and were both posted back to the UK and joined the same Maintenance Unit at Colerne near Bath as test pilots, and, by a strange quirk of fate, the same 122 Squadron as part of the 2nd Tactical Air Force in the build-up to D-Day. They looked after each other in the air and on the ground and became the best of friends. Allan was best man when John and Cecile were married, is currently living in Shropshire and has written his own story, Born to Survive , published by Ellingham Press. He was also very willing to share his stories of their times together and give me permission to use quotes from his book, and has been good enough to write a foreword. When this book is published, he has agreed that he and I will play a game of golf and raise a glass to Johnnie. It will be my privilege, and all the more remarkable as Allan is now 94 and still plays.

The National Archives at Kew and the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich both deserve a mention, as they willingly help anyone trying to research a project such as this.

The book would also not have been possible without the help of everyone at The History Press, but in particular Shaun Barrington and Jo De Vries.

Finally, a word of thanks to my wife, Sue, who has put up with my absence whilst I have researched and written this book. I could not do without her love and support.

Contents

It is incredible how in times of danger, sincere and lasting friendships are formed. So it was with Johnnie and myself during the Battle of Malta. We flew daily in combat, often as a pair against the bombers and fighters attacking the island, and became firm and lasting friends.

Johnnie was a forceful character, pugnacious and fiery, with a wicked sense of humour which he retained even in the dark days of Malta. His laugh was infectious but he was not the sort to take rubbish from anybody. Always a pleasure to be with his habit of twirling his moustache springs instantly to mind it is a renewed pleasure for me to see him again in the pages of this book.

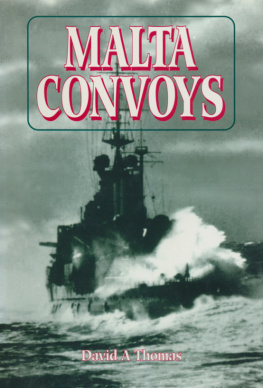

This book describes in detail the Malta convoys of 1942 and portrays graphically the bravery of the merchant seamen who were constantly attacked before reaching the island.

Allan Scott DFC

Prologue

Early Morning

13 August 1942

T hey had made it through the night, but only just. Captain David Rattray Macfarlane OBE had manoeuvred his ship, the Melbourne Star , into position with what remained of the convoy in single line. Rochester Castle was leading, followed by Waimarama , then his ship the Melbourne Star with the Ohio behind him. Port Chalmers was some way behind and had not caught up with them.

On the bridge of the Melbourne Star , Macfarlane peered into the darkness before first light and wondered what else could be thrown at the convoy. Only half the convoy had survived the night and daybreak would bring no relief, only more Axis bombers and, for all he knew, Italian cruisers and destroyers as well. Aboard the depleted escorts and merchant ships of the convoy, haggard and exhausted men stood ready to repel what could be the enemys next decisive attack. Very few gave themselves much of a chance. Against everything that the Axis could launch against the remains of the convoy, there seemed little that the remaining ships could do except go down fighting.

Despite the repeated attacks, Macfarlane was aware that the damaged tanker the Ohio was still making decent progress. Supreme efforts were required to hold the damaged vessel on her course. Her deck had been split across the centre almost to her amidships and with every yaw of her helm the buckled metal tore and groaned, threatening to break the entire ship in half. It was necessary to keep a continuous 5 degrees on the starboard helm to compensate for the pull caused by the great gouge in her side. By 3 a.m. the tanker had managed to reach a speed of 13 knots and by dawn she had caught up with the remainder of the convoy.

They had been expecting attacks from the Italian Navy all night; it was a miracle that there had been none. In fact the Italians had withdrawn and steamed away from the convoy because Air Vice Marshal Park, in charge of the RAF on Malta, had sent out what available aircraft he had and ordered them to illuminate the Italian cruisers and regularly return to Malta, to convey to the Italians that a strike force of considerable size and power was on its way. This was followed up by an attack from a single Wellington and an illuminate and attack call to non-existent Liberators, which resulted in the Italian cruisers making a course for Palermo.

Good fortune, fortitude and deception had all played their part, but this did not concern Rear Admiral Burrough, who had deployed what was left of his escorts to fight a defensive action against the expected surface attack from the Italians. The force available to him was hardly impressive, however. Other than three minesweeping destroyers, he could only muster a damaged cruiser, HMS Kenya , and HMS Charybdis as heavy ships and four big Tribal-class destroyers, including HMS Pathfinder . HMS Bramham was standing by the abandoned Santa Elisa , HMS Penn was coming up from astern with Port Chalmers while HMS Ledbury was close to the Ohio , but they were about 5 miles astern of the main body which now consisted of the Melbourne Star , Waimarama and Rochester Castle .

1435 SQUADRON AIRBORNE

Everything now depended on the convoy from the west. Johnnie Mejor squinted into the rising morning sun, wondering when they would receive the order to take off. Maltas surviving Beaufighters had patrolled what was left of the convoy in the hours of darkness as it slipped through the narrow channel between the coast of Tunis and the western tip of Sicily, but the really dangerous time began now, with the dawn, as the surviving merchant ships and oil tanker with their escorts entered bomb alley and the final run to the beleaguered island.

Next page