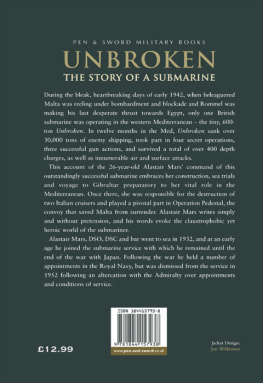

UNBROKEN

UNBROKEN

THE STORY OF A SUBMARINE

by

Alastair Mars, D.S.O., D.S.C. and Bar

First published in Great Britain in 1953 by

Frederick Muller Ltd

Published in this format in 2006

and reprinted in 2008, 2011, 2012 and 2013 by

PEN & SWORD MARITIME

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Alastair Mars, 1953, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2012, 2013

ISBN 978 1 84415 793 8

The right of Alastair Mars to be identified as Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

By CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Archaeology,

Pen & Sword Atlas, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

To the undying memory

of

LIEUTENANT JOHN RENWICK HAIG HADDOW

D.S.C., ROYAL NAVY

and all those Sub-mariners who did not return

PROLOGUE

A Ship is Born

NOVEMBER, 1941. Kharkov had fallen and the German army advanced through the snows towards Moscow. In Africa the New Zealanders captured Bardia and General Auchinleck launched the offensive that was to result in the relief of Tobruk. In the Mediterranean, the disasters of Greece and Crete still fresh in our minds, we were doing no more than hold our own. The Ark Royal had been sunk, and Mr. Churchill told Parliament that we were losing a monthly average of 180,000 tons of merchant shipping. While Chiang Kai-shek called upon the Western Powers to join in the war against Japan, America remained uneasily neutral. In Yugoslavia the Tcheckniks under Mihailovitch harried the German occupation forces. Nuremberg had been bombed and Marshal Ptain led the government of occupied France. The conquest of Abyssinia and the defiance of Malta were two bright stars in a black, uncertain night.

At home the people of Britain went about their business with that quiet confidence other nations call arrogance. There was rationing, the Windmill Theatre and jokes about Woolton Pie and the Home Guard Nightly raids on Merseyside and London Walt Disneys Fantasia and the Polish Army choir A million women employed in munition factories As they hammered rivets, forged steel, and dug at bomb dbris, sports fans discussed the recent soccer international in which England had beaten Scotland by two goals to nil.

Farmers tended their fields, fishermen cast their trawls, miners sweated in the ugly darkness of the pits. Aircraft, tanks, bombs and shells rolled from the production lines. Housewives worked miracles with the rationsand found time to drive ambulances and man Wardens Posts. Children were educated and grandparents came from retirement to do their bit. Parks became allotments, taxis hauled fire pumps. As scientists evolved new and more terrible weapons of destruction, a lunatic fringe demanded peace at any price. In the drive for scrap, park railings became Bren-carriers, dustbins destroyers and aluminium saucepans Spitfires.

And at Barrow-in-Furness in this gloomy, mournful November, as just one tiny part of the great wartime scene, a ship was being born.

It was a grey, depressing afternoon, and as the taxi rattled from the station to the Victoria Park Hotel, my wife huddled closer to my side. Occasionally she shivered, not from cold, but at the bleak melancholy of Barrow. For my part, I was too excited to be affected by the ugliness of industrial Lancashire. At last, after months of nail-biting impatience as captain of a training submarine, I was on my way to take command of the Unbroken. She had been launched some months earlier by the wife of Tubby Linton, one of the greatest of all submarine commanders, and was near completion. Only God and the Sea Lords knew what the future held for me, but it could be no worse than the soul-destroying repetition of training duties. Understandably, Ting, my wife, did not see things that way; apart from other considerations, no woman likes to have her husband leave her when she is expecting a baby.

I was twenty-six years old and bubbling with enthusiasm. To use the expression of the day, I was mad keen. Perhaps a little apprehensive, too. For it was no small responsibility to have the lives of thirty-two officers and men dependent, to a very large degree, upon the efficiency of my leadership. In a submarine, fifty fathoms deep, there is no second chance, no opportunity for apologies. With the crew as the fingers, and the captain as the brain, you can compare it to an engineer removing the fuse from an unexploded bomb. When the fingers are supple and responsive the fuse will be removed safelyif the brain transmits the right messages.

It was then my turn to shiver, but with the self-assurance of youth I quickly brushed aside such thoughts and speculated, instead, on how soon I would take the Unbroken to sea.

At the hotel we quickly checked our bags and made for the bar. We were greeted by a host of old friends. There was Tubby Linton, waiting to take the submarine Turbulent to the Mediterranean; Paul Skelton, standing by to deliver a newly built submarine to the Turks; Lieut.-Commander Maitland-Makgill-Crichton (oddly, he did not boast a nickname, and was always called Maitland-Makgill-Crichton) then captain of the destroyer Ithurial. There were others, too, but seeing Paul Skelton affected me most.

The son of a Bishop of Lincoln, he had entered Dartmouth at the same time as myself, and throughout our parallel careers we had remained close friends. Slim, dark, athletic, he filled exactly the popular conception of a naval officer. We had enjoyed and suffered much together. Together we took our sub-lieutenants course, played games, joined the submarine service, were on the China station, and survived the hideous slaughter of our Mediterranean submarines in the early days of the war. It is a curious thing, but serving in submarineswhether as officer or ratingis like being a member of a Service within a Service. Its members are bound together with a camaraderie unequalled elsewhere, and to me Paul Skelton represents all that is finest in that select body of men.

We have all our own particular memory of the September afternoon when Mr. Chamberlain announced the declaration of war. On that Sunday I was navigator of the submarine Regulus, and was drinking with a group of friends at the United Services Club, Hong Kong. Apologetically, a Chinese steward told me I was wanted on the telephone. It was Signalman Cheale calling from the Regulus. Sorry to bother you, sir, he began, but the balloons gone up.