Contents

Page List

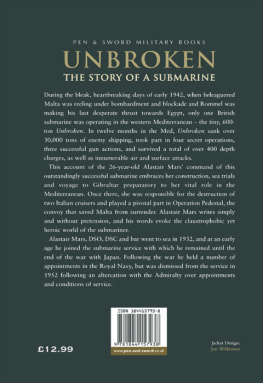

Submarine Commander

A STORY OF

World War II and Korea

Captain Paul R. Schratz, USN (Ret.)

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY

Frontispiece: Commander Paul Schratz on return to Pearl Harbor after Korean War. U.S. Navy photo.

Copyright 1988 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schratz, Paul R., 1915

Submarine commander : a story of World War II and Korea / Paul R. Schratz

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8131-1661-9 ; ISBN 0-8131-0988-4 (pbk : alk. paper)

1. Schratz, Paul R., 1915. 2. United States, NavyBiography. 3. World War, 19391945Personal narratives, American. 4. Korean War, 19501953Personal narratives, American. 5. World War, 19391945Naval operationsSubmarine. 6. Korean War, 19501953Naval operationsSubmarine. I. Title.

V63.S38A3 1988

940.54'51'0924dcl9

[B] 88-19035

ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-0988-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

Any commander who fails to exceed his authority is not of much use to his subordinates.

Admiral Arleigh Burke

Chief of Naval Operations

Maps

Preface

Submarine warfare is unique in many ways, different from our preconceptions of strife, different from all previous combat in American history, different even from the visions of war by American military planners at the opening of hostilities on 7 December 1941. And it may be a facet of war never again to be fought by American undersea forces.

Strange as it seems, combat is a rare experience for the man in uniform, even in time of war. Edward Luttwak determined that Americans landing in Normandy in 1944 engaged in actual combat for only a few weeks at most during the Allied sweep across Europe in the eleven months before V-E Day. On the eastern front, where Germans and Russians were in contact for over four years, months passed between the days of intense battle, with rare exceptions such as the Stalingrad fighting which lasted for weeks at a time. Other than bomber and submarine crews, German Panzer troops, and the U.S. Marines, a very small fraction of the tens of millions in uniform accounted for a very large proportion of total days in action.

My distinguished friend and submariner Captain Edward L. Beach, Jr., USN Retired, found that the U.S. Navy before World War II spent a total of twenty years at war with real shooting in only about eleven years and time spent in actual battle only about fifty-six hours. Throughout World War I, no U.S. Navy surface ship fired at or was fired upon by a German surface warship.

In World War II the U.S. Marines were an exception to the limited experience in combat. The average Marine serving from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay spent 120 days in combat. Far surpassing this figure were the submarine forces, both German and Allied.

In the Battle of the Atlantic, the longest and most tragic campaign of the war, the U-boats wreaked enormous damage to Allied shipping at the terrible cost of 28,000 men lost, 85 percent of the entire force. American submarines, fighting a shorter war with a force representing only 1.6 percent of the Navy, accounted for 55 percent of Japan's total maritime losses. Again a heavy price was paid for victory. The loss of fifty-two American submarines carrying 375 officers and 3,131 crewmen either down with their ships or to lingering deaths in prison camps was the highest casualty rate for any element of the U.S. armed forces. Of unique significance, the U.S. undersea warriors sank twenty-seven enemy ships for each submarine lost, the Germans only four.

The average submariner, German or American, operated in enemy-controlled waters, or under direct threat from enemy submarines, aircraft, and minefields during most of his time at sea. The first U.S. submarine departed from Pearl Harbor on a war patrol in Japanese home waters on 11 December 1941. From that day until 14 August 1945, when the last ship was sunk the day before the surrender, our submarines ranged the broad Pacific, penetrating bays, harbors, and seaports of the enemy's innermost defenses, often thousands of miles from the nearest friendly support.

They sank 1,178 merchantmen and 214 warships totaling 5.3 million tons. The warship sinkings included a battleship, 8 aircraft carriers, 11 cruisers, and numerous destroyers and submarines. In addition to the shipping losses inflicted on Japan, U.S. submariners rescued 550 U.S. and Allied aviators from death or imprisonment, landed and recovered spies and coastwatchers, made commando raids, supplied aviation gasoline, ammunition, and stores to isolated U.S. forces, conducted special intelligence operations, launched rocket attacks against enemy shore installations, acted as beacons and weather forecasters for the carrier forces, and photographed beach areas for amphibious landings. The submarine blockade of Japan cut off oil, gasoline, and heavy metals for her industry. The dwindling Japanese air force and navy were forced to rely on fuel made from soybeans; domestic transport was powered by crude charcoal burners.

I wrote Submarine Commander partly to express a special debt of gratitude to the men back aft, the superb chiefs, key petty officers, and the men who were so vital an element in the success of our American submarines. With virtually no choice of the captains or execs under whom they would serve, some great and some less great, they did a masterful job, often under extremes bordering on hopelessness and despair. Their mechanical genius in keeping their intricate warships operating under seemingly impossible conditions may have been equaled but never surpassed. Through utmost misery they never lost their sense of humor, whatever the occasion. After the war, many attained distinguished positions in civilian life yet, whatever their achievements, the war years remain the ultimate experience, a continuing source of pride in a tough job very well done. Like all combat veterans, they recall the comradeship and intensity of life more vividly than the horror and brutality. If their stories of adventure on and under the seas seem to diverge in significant detail, one need only recall that memory is a convenience store often in need of replenishment.