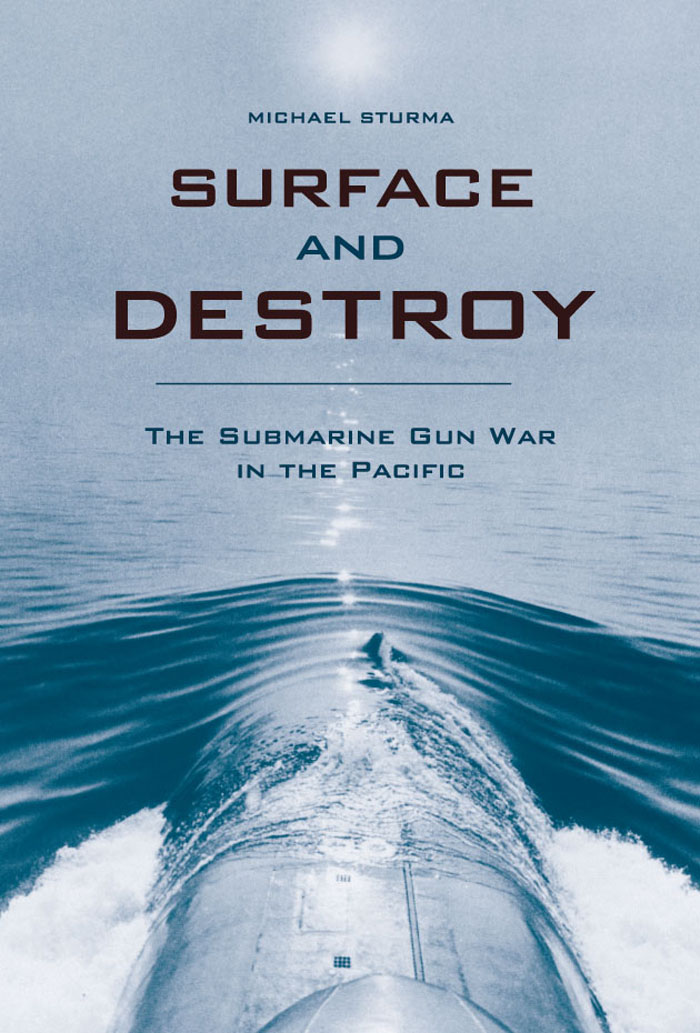

SURFACE AND DESTROY

SURFACE

AND

DESTROY

THE SUBMARINE GUN WAR

IN THE PACIFIC

Michael Sturma

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY

Copyright 2011 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

15 14 13 12 11 5 4 3 2 1

Maps by Jeff Levy, University of Kentucky Cartography Lab

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sturma, Michael, 1950

Surface and destroy : the submarine gun war in the Pacific / Michael Sturma.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-2996-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-2999-0 (ebook)

1. World War, 19391945Naval operationsSubmarine. 2. World War,

19391945Naval operations, American. 3. World War, 19391945

CampaignsPacific Ocean. I. Title.

D780.S78 2011

940.5451dc22

2010047402

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

To Susan and Barbara

Contents

Acknowledgments

As they had during my previous research on World War II submarines, Charles Hinman and Nancy Richards of the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum at Pearl Harbor made me feel a welcome visitor. I owe special thanks to Charles for his assistance with many of the photos in this volume, and for contributing information from his Web site, On Eternal Patrol.

Molly Orme patiently helped me at the Australian Archives in Melbourne, and John R. Waggener assisted with research materials from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. I have benefited from the advice of Nathaniel S. Patch at the National Archives and Records Authority, College Park, Maryland, and of Roy Grossnick, head of the Operational Archives Branch at the Naval Historical Center, Washington, DC. Tim Frank assisted with research at the National Archives and Records Authority, and Robert G. Price helped garner material at the Submarine Force Museum in Groton, Connecticut.

I gratefully acknowledge the support of a Vice Admiral Edwin B. Hooper Research Grant by the Naval Historical Center, an Australian Army History Grant, and the Research Excellence Grant Scheme administered by the International History Group at Murdoch University in Perth.

This is an opportunity to publicly express my appreciation to colleagues at Murdoch University: Andrew Webster, Jim Trotter, Alex Jensen, and John Dunhill. Ian Chambers generously afforded IT support. I owe special thanks to Michael Durey for his years of support, both as an academic and as a friend.

I have also been extremely fortunate to have the unstinting support of family, including Joan and Rell Roberts; my sisters, Susan Witt and Barbara Eblen; their respective husbands, Wes and Mike; and their now-adult children, Thomas, Lauren, Heather, and Nicci. As always, with love, I thank my wife, Ying, for helping me negotiate the intricacies of information technology as well as many other challenges and opportunities that have come along.

Introduction

For a submarine crew there was no maneuver more exhilarating, or more fear-inducing, than a surface gun action. Relying on surprise and speed, the submarine would suddenly punch through to the surface, while half-drenched sailors scrambled through the hatches to reach their guns and ammunition lockers. A crack team aimed to get off the first shots within twenty seconds of surfacing. Men who were usually kept cramped beneath the sea were at last unleashed to encounter the enemy face-to-face.

For Ignatius Pete Galantin the human face of the enemy materialized when the USS Sculpin battle surfaced to attack a sampan in 1943. The submarine quickly riddled the small wooden craft with bullets, leaving a heavy tang of gunpowder hanging in the air that enveloped even those below decks. When the Sculpin moved in closer to the sampan the crewmen witnessed the effects of their automatic weaponsthey were close enough now to see the purple eruptions of bullets in bodies and the blood-stained water sloshing in the bilges. How different, how personal was war when the target was flesh and blood instead of steel, Galantin observed.

His experience was far from exceptional. George Grider recalled a similar incident when he ordered the USS Flasher to gun attack a sampan. After the craft burst into flames and it appeared that the occupants had jumped overboard, the Flasher pulled alongside to lob in hand grenades. A man who had been hiding behind the gunwales leaped up and went overboard, but not before staring directly at Grider with an expression of piercing accusation. At least for that moment, Grider recalled, the war had become intolerably personal.

These Allied attacks have been well documented and constitute the main criteria for submarine success in the Pacific. It is a view, however, that is incomplete.

There was another side of the submarine war most often ignored or dismissed. These were surface gun attacks, often on relatively small craft such as patrol boats, schooners, sampans, fishing trawlers, and junks. The Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC), established to record the losses inflicted on Japanese shipping, deliberately excluded vessels of under 500 tons from its investigations.

Often the stories of these attacks run counter to the good war narratives that tend to dominate interpretations of the Allied experience during World War II. As Geoffrey Till reminds us in writing about the battle of the Atlantic, though, historians should never forget that the war at sea was not some kind of giant board game, but cruel hard war in all its horrors. The brutality of total war became starkest on the surface.

This is not to question the heroism so evident in the submarine war, but to offer a more nuanced account. While surface actions encapsulate the horror of war, they also reveal a transcendent humanity. If close-up encounters magnified the cruelty of war, they also extended the potential for mercy. Given that submarines typically operated with a high degree of autonomy, we can find examples at both extremes. As emphasized in the pages that follow, many submariners acted on their conscience rather than following the logic of unrestricted warfare.

Using submarines as submersible gunboats was nothing new. German U-boats had employed their deck guns extensively against Allied shipping in coastal waters and in the Mediterranean during the First World War. They continued the practice during World War II; during one week in November 1942, for example, the German ace Wolfgang Lth sank four ships using the