Contents

ALSO BY IAIN BALLANTYNE

The Deadly Deep

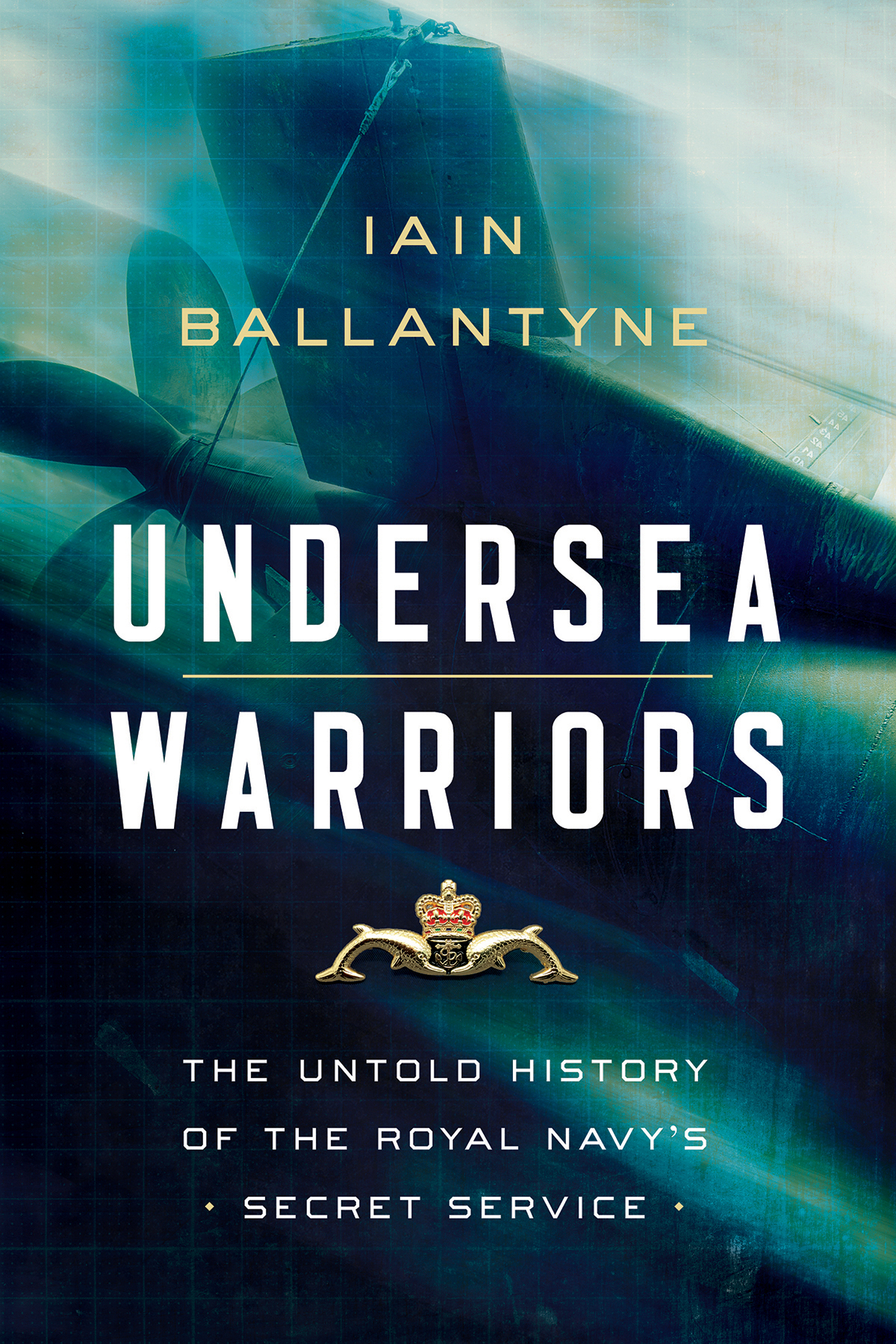

UNDERSEA

WARRIORS

THE UNTOLD HISTORY OF THE

ROYAL NAVYS SECRET SERVICE

IAIN BALLANTYNE

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

U NDERSEA WARRIORS

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Iain Ballantyne

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition September 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher,

except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review

in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this

book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or

by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-213-6

ISBN: 9781643132761 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

To the Royal Navy submariners who fought and won the Cold War and their families, not forgetting the shipbuilders, the support staff and good friends in the United States Navy submarine force.

CONTENTS

Theyll never be any use in war and Ill tell you why:

Im going to get the First Lord to announce that we

intend to treat all submarines as pirate vessels in

wartime and that well hang all the crews.

Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson, Controller of the Royal Navy, 1901

S ince the early days of the twentieth century the Silent Service, as the submarine arm of the Royal Navy is known, has won 14 Victoria Crosses. This is more than any other branch of the British fleet. Even old Arthur Wilson, who won the VC himself, for engaging the enemy in hand-to-hand combat during the Sudan campaign of 1884, would surely have admitted the undersea warriors he loathed so much were pretty brave fellows.

In the case of submariners there has always been an added level of valour. This was especially so in the early days, when they also had to contend with utterly appalling, life-threatening conditions posed by the very vessels in which they went to war.

Wilson was not alone in taking a dim view of submariners. There were many others in the Royal Navy who regarded the new breed of pirates in their midst as offering dubious military worth.

How on earth could one of those tiny, impertinent boats be allowed to affect a battle at sea? For a start, the people who operated them were dangerous eccentrics, lacking discipline and simply not gentlemen. Arthur Wilson also allegedly blustered that submarines were underhand and damned un- English!

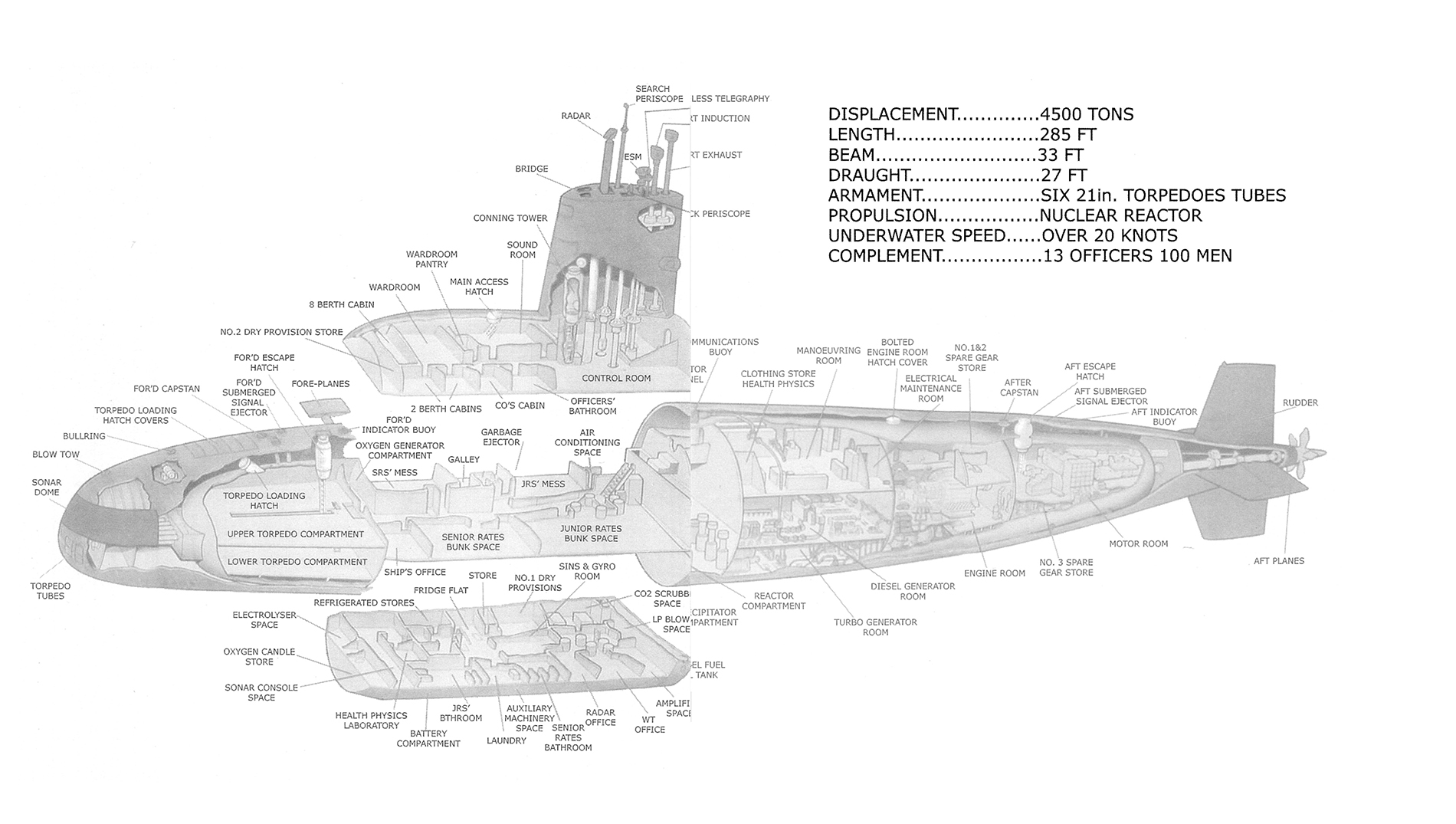

Anyone associated with submarines was, so the doubters believed, to be regarded as a criminal, indeed a lunatic. Right from the earliest days of British submarine operations, the sanity of men who ventured beneath the waves in their boats they were not even proper ships was a matter of debate. Who else but a madman would go to war under the sea, inside a tiny metal tube that, in most cases, did not even boast a toilet? During the First World War submariners were sometimes forced to stay submerged for many hours at a time. With no recourse to fresh air or means of dumping human waste overboard they had to do their business, so to speak, in a bucket.

Sometimes the air became so foul a submarines own engines stopped working, as if out of protest at the sheer horror of it all.

Inside a submerged boat the stench of urine and faeces was combined with sweat and grease, the aroma of unwashed bodies and filthy clothes. Fresh water was invariably in short supply, so submariners would not bathe for days, if not weeks. Not for them a shave each day nor crisp clean clothes. The food could be equally foul.

Aside from the enemys homicidal intent, the boat herself could spring a leak or suffer some form of catastrophic mechanical failure that might kill everybody. Or at least make the chances of survival close to zero.

The Engineer-in-Chief of the Royal Navy, Sir John Durston, disowned the early British submarines. He pointed to the danger posed by running petrol engines in an enclosed space with no means of ventilation while submerged. He did not want the deaths of sailors from carbon monoxide poisoning on his conscience. The embarkation of white mice as an early-warning device was another eccentric facet of the weird world of submarining. If their little lungs couldnt cope with the foul and fetid atmosphere then it wouldnt be long until the humans couldnt either. Durston suggested submersibles were unviable until a different means of propulsion could be found. Elsewhere, the Director of Naval Construction totally rejected submarines. He regarded them as lunacy, what with their blundering around beneath the waves with no means of seeing where they were going. Navigation was by guesswork. Their primitive periscope used a knuckle pivot on the outside of the hull, so it could be swung up, rather than extended vertically from inside the boat as later became the practice.

The image also rotated as the scope rotated. It was better than no sight at all, but not much. As if that wasnt bad enough, while submerged the switch controls for the electric motor sparked frenetically. At any moment they might ignite petrol or diesel fumes, creating an inferno that burned both mice and men to a crisp.

Running on the surface with the hatch open, during recharging primitive batteries emitted poisonous gas. Death was a close companion for the early British submariners.

Their clothes, whether ashore or out on the ocean, always stank of petrol or diesel fumes, with a hint of vomit. The first generation of British boats rolled wildly while on the surface in anything but a flat calm sea, so throwing up was a normal activity. Then there was the customary tinge of excrement (more of that shortly) and the aroma of cooking grease to finish off the distinctive scent of the submariner.

Those boats lucky enough to possess some form of toilet had to follow a careful procedure to evacuate the offending faecal matter. The toilet pan had to be pumped out by hand or with the assistance of high-pressure air. While submerged it was essential not to use up all the air in the boat, so the toilet pan was not cleared until absolutely necessary. This meant quite a pile of human waste. Sometimes there would be a blowback during the pan evacuation process. The unfortunate sailor most often the new boy in a crew would get blasted in the face. Consequently, the wise submariner would adopt the tactic of sidling in crablike, head well below the top of the pan. He would operate the various levers and valves with utmost caution. If there was blowback it would cover only his clothes, hands and hair. The submarine stank most on its return from a patrol. The crew would have no idea how bad it was or how much they reeked for their olfactory senses had long ago been desensitised.

In those submarines lacking a toilet efforts were made to deploy the bucket when the boat was surfaced. The submariner did his business by hovering over it while the receptacle sat on the casing. The contents were then tipped over the side. In those boats blessed with a toilet, the trick was to make sure the expulsion of its contents while submerged did not betray the submarines position to the enemy. Air bubbles and brown stuff on the surface were a dead giveaway.