Fast Tanks and

Heavy Bombers

I NNOVATION IN THE U.S. A RMY , 1917-1945

D AVID E. J OHNSON

Cornell University Press

I THACA AND L ONDON

To Wendy

Contents

Tables

Acknowledgments

This book is the product of an intellectual odyssey that started in 1987, when the U.S. Army gave me, a serving officer at the time, the extraordinary opportunity to enter the graduate program in history at Duke University. During three wonderful years at Duke, I enjoyed the privilege of working with a community of scholars who took quite seriously their obligations as educators. My development as a historian is the direct result of the efforts of Joel Colton, Calvin Davis, W. A. B. Douglas, Larry Goodwyn, I. B. Holley Jr., Tim Lomperis, Kristen Neuschel, Alex Roland, Theodore Ropp, Bill Scott, and Peter Wood. I thank them all.

I am particularly indebted to Alex Roland, I. B. Holley Jr., and Larry Good-wyn. Alex Roland subtly challenged me to grow out of my preconceptions and introduced me to colleagues who have fundamentally influenced my work. Finally, Alex helped me gain and maintain control over this project. I. B. Holley gave me the rigorous grounding in research methodology and scholarship that enabled me to conceptualize and write this book. Larry Goodwyn introduced me to social history, helped me understand institutions, and in the process significantly influenced the way I have come to view my work and the world.

Many institutions and individuals have been particularly helpful. The staff of Perkins Library at Duke University provided every possible assistance. Stuart Basefsky and Ken Berger were always there when I needed help. Marty Andresen, John Slonaker, Richard Sommers, and David Keough led me through the holdings of the U.S. Army Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. Richard Morse, Tim Johnson, Robert Johnson, and Archie DiFante provided similar support at the U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. These people made the use of their institutions resources an enjoyable experience.

Later I had the good fortune to work in the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C. My colleagues there, particularly Jeffrey Clarke, Harold Nelson, Roger Cirillo, Kavin Coughenaur, Edward Drea, John Elsberg, John Greenwood, Roger Kaplan, Jim Knight, and Frank Schubert, gave steadfast assistance and encouragement.

I continued revising this book while serving at the National Defense University, first as a member of the faculty of the School of Information Warfare and Strategy, then as the director of academic affairs. David Alberts, Ken Allard, Brad Barriteau, John Carabello, Karen Carleton, Rob Cox, Tom Czer-winski, Jim England, Fred Giessler, Gerry Gingrich, Alan Gropman, Dan Kuehl, Martin Libicki, Michael McDevitt, Ervin Rokke, Rudy Rudolph, Jim Stafford, Susan Studds, and Dave Tretler all helped me bring the book to closure. John Alger provided useful critiques and invaluable editorial assistance. By challenging some of my assertions, my students at the National War College and the Information Resources Management College helped me tighten my arguments.

I finished this book in my new life as a civilian. Four colleagues at Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), Bill Owens, Jim Blaker, Dr. Ed Frieman, and Wendy Frieman, listened to my arguments about military innovation and RMAs (revolutions in military affairs) and offered valuable insights.

The long process of writing this book was immeasurably aided by Roger Haydon, my editor at Cornell University Press. Roger worked with me over several years and showed extraordinary patience when the demands of my life forced delays in the completion of the manuscript.

Five other people have made this work possible. My late father, Eugene

E. Johnson Jr., fostered my interest in World War II. Like many other men who served in that war, he became an armchair historian in an effort to understand his personal experience. This book originated in his interests and doubts, often expressed as asides as we watched motion pictures about the war. I thank Tim Tyson for reading this book in an earlier incarnation and being a friend in every sense of the word. Whenever the frustrations of the process approached the unendurable, I could always turn to Tim.

The freedom to devote an extraordinary measure of my time and energies to this project was made possible by the sacrifices of Sharon Johnson and our son, Sean Johnson. It took me seven intense months to write the first draft of this bookand seven years of stolen weekends to complete it. Without their support and understanding, I could not have completed it.

Finally, I want to thank Wendy Friemanthe woman who has changed my life. To her I dedicate this book.

D. E. J.

Washington, D.C.

Introduction

History is lived forward, the English historian C. V. Wedgwood perceptively noted, but it is written in retrospect. We know the end before we consider the beginning and we can never wholly recapture what it was like to know the beginning only. This cognitive constraint is particularly compelling in a study of the U.S. Army between the two World Wars. Conditioned by the reality of World War II and some fifty years of a large, standing postwar army, we find it too easy to assume we know what needs to be analyzed.

The most familiar version of the Armys fate during the interwar era suggests that although it endeavored to maintain its readiness, the Army was unprepared for the enormous demands of World War II. A miserly Congress, supported by a peace-minded and isolationist American public, denied it the funds and personnel needed to maintain an adequate military establishment. The official history of the U.S. Army emphasized that this public and official malaise had dire consequences. The Army became tragically insufficient andincapable of restoration save after the loss of many lives and the expenditure of other resources beyond mans comprehension.

This view of the origins of the Armys unpreparedness at the beginning of World War II is important for at least three reasons. First, the successes of World War II are the bedrock on which existing American military doctrines are constructed. Second, the high costs of American unpreparedness at the beginning of World War II served to justify large standing military forces and their associated defense budgets in the postwar years. Third, the lessons of the interwar era provide compelling arguments to avoid the dismantling and neglect of American defense institutions at the end of the cold war. Thus, the interwar period is frequently cast as one analogous to the present post-cold war era, with its ambiguous threats to American security and concomitant demands for cuts in defense spending and smaller military forces.

In this book I present a different perspective on the interwar Army. I argue that internal barriers to change and the myopic vision of single-issue constituencies contributed significantly to the Armys unpreparedness for World War IIperhaps more so than the external challenges. Even though the Army faced severe resource constraints, it also had intellectual and institutional deficits that exacerbated shortfalls in money and personnel.

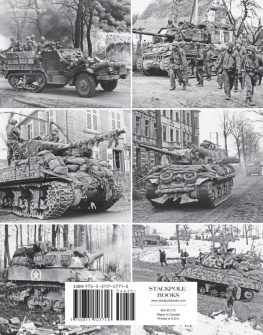

I focus on the adaptation of the U.S. Army to the realities of modern war by analyzing how the Army responded to two technologies that had demonstrated their military utility in World War Ithe tank and the airplane. The military forces of France, Great Britain, Germany, and the United States had all experimented with tanks and airplanes on the western front. During the two decades that followed the Great War, these nations and others grappled with the implications of these new weapons and debated the means by which the technologies would be assimilated into their military institutions. From the conceptual choices, tank and airplane doctrines and designs emerged. The results varied from country to country.

Next page