ANGUS KONSTAM

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

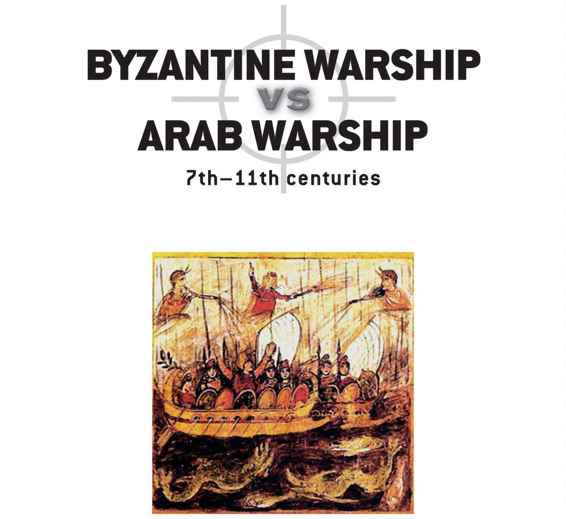

The maritime contest between the Byzantine dromn (pl. dromnes) and the Arab shaland (pl. shalandiyyat) began in the mid-7th century and lasted for the best part of four centuries. In their heyday the dromn and shaland fought each other from one end of the Mediterranean to the other. By the mid-11th century, though, a new form of galley favoured by the Italian city-states the galea rose to prominence in the Byzantine and Arab navies, and eventually replaced the remaining dromnes and shalandiyyat.

In this detail of the well-known Greek Fire image from John Skylitzes Synopsis historion, we see that this very stylized Byzantine dromn is a bireme with a single lateen-rigged mast, and what appears to be a single steering oar. While the bow and stern are both rounded, there is no sign of a spur of any kind. Shields are hung along the side of the vessel.

This depiction of an Arab vessel is an Egyptian graffito of the late 7th century, and shows a small craft fitted with a single mast and lateen sail, steeply sloping bow and stem posts, and what may be a fighting platform in the bow, below the decorative tip of the stem post. It has been suggested that this is an early representation of an Arab shaland, even though the vessel lacks any oars.

The Arab and Byzantine warships owed much to their Roman predecessors in terms of design and fighting potential. Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD , what was once Romes mare nostrum (our sea) became a naval battleground as barbarian fleets and pirates preyed on Roman shipping. By the 6th century, however, the Byzantines had developed their own powerful navy, which saw off the maritime threat posed by the Vandals and Ostrogoths in the Western Mediterranean, and this fleet spearheaded the revival of Byzantine fortunes during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I (r. 52765). By the close of the 6th century the Byzantines not only controlled the former Eastern Roman Empire, but had reconquered territory in Italy, North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula as well. While many of these recaptured Roman provinces were little more than narrow strips of territory fringing the coast, Byzantiums powerful fleet served as the glue that bound this largely maritime Empire together. For more than a century, Byzantium was the unchallenged master of the sea, from the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar) to the Nile Delta.

That all changed in the early 7th century. For centuries the Eastern Roman Empire and its Byzantine successor had waged an intermittent war against the Sassanid Persian Empire. In 611 the Sassanids overran Byzantine Syria, and within nine years they had conquered Egypt and much of Asia Minor. In 626 they even laid siege to Constantinople, but the city defences held, and eventually the Byzantine navy attacked and defeated the Persian fleet and lifted the siege. A Byzantine counterattack reconquered much of the lost territories in Asia Minor and the Middle East, but the war left the Empire financially and militarily weakened. It was at this crucial moment that a new foe appeared one that would not just threaten the Byzantine Empire it would dismember it. While the Byzantines and Persians had been at loggerheads the Islamic prophet Muhammad (c.570c.632) emerged as the leader of a militaristic spiritual movement which had captured Mecca, and went on to conquer most of Arabia. So began what became known as the Arab Conquest a religiously inspired explosion of military and political power that transformed the known world. While at first the Arabs lacked a navy and found themselves vulnerable to attack from the sea, they soon developed a formidable fleet that confounded Byzantine expectations in the early years of the Arab Conquest most spectacularly at the Battle of the Masts (Dht al-sawr) in 655. The Arabs would prove themselves a doughty adversary over the centuries that followed, making the Romans unchallenged supremacy in the Mediterranean a distant memory.

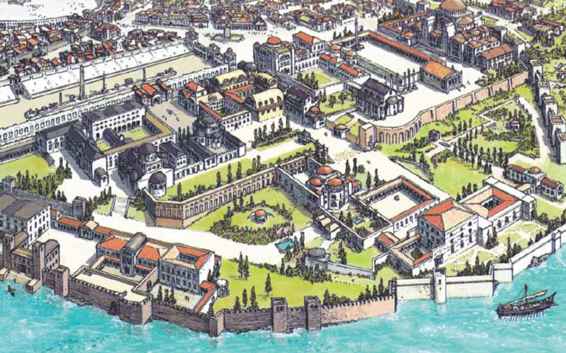

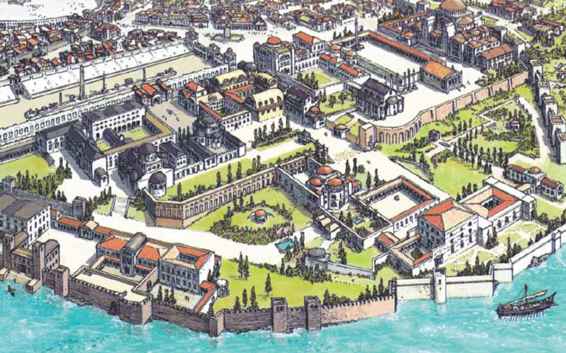

During this period Constantinople (now Istanbul) was encircled by formidably high walls, which also covered the seaward side of the city. In this depiction of the 7th-and 8th-century city by Oliver Frey the little harbour on the left is Eleutherios, where the remains of two small Byzantine warships were discovered in 2005, during building work to expand the citys metro system.

Their nature of both dromn and shaland changed substantially over the period. At first they were single-masted monoremes, with limited space for marines and weaponry. These were the galleys that duelled with each other during the 7th and 8th centuries. These monoremes were then superseded by larger versions bireme galleys with two masts, and more substantial fighting areas on board. These later warships remained in Arab and Byzantine service until the end of our period. Both the dromn and the shaland carried marines as well as oarsmen, whose task was to capture enemy warships by boarding them. However, they also carried a range of missile weapons, from stones and arrows to javelins, darts and large iron bolts. Most dramatically of all, the Byzantines also possessed their great secret weapon Greek Fire a highly flammable terror weapon that played a decisive part in the very survival of the Byzantine Empire. The secret was eventually learned by the Arabs, thereby ensuring that naval warfare during this period was a brutal, violent and murderous business. The real stars of this maritime history, though, are the ships themselves the dromnes and shalandiyyat that once dominated the blood-soaked waters of the Mediterranean.

CHRONOLOGY

| 476 | Romulus Augustus (r. 47576), the last Western Roman Emperor, is deposed. |

| 52765 | The reign of Justinian I: Byzantine forces reconquer much of Imperial Romes possessions in Africa, Dalmatia, Sicily, Italy and Spain. |

| 60228 | War between the Byzantine Empire and Sassanid Persia leaves both powers gravely weakened; initial Persian success give way to a pyrrhic victory for the Byzantines under Emperor Heraklios (r. 61041). |

| 632 | The Prophet Muhammad dies after conquering Mecca and establishing Islamic rule in the Arabian Peninsula; he is succeeded by the Rshidn (Rightly Guided) caliphs (63261). |

| 63438 | Arab forces conquer Byzantine Syria, winning a decisive victory at Yarmouk (636). |

| 640 | Arab victory at Heliopolis heralds the Islamic conquest of Byzantine Egypt. |

| 641 | Alexandria, the Egyptian capital, falls to the Arabs; a Byzantine fleet lands troops that recapture the city in 645, but are defeated by the Arabs at Nikiou in 646. |

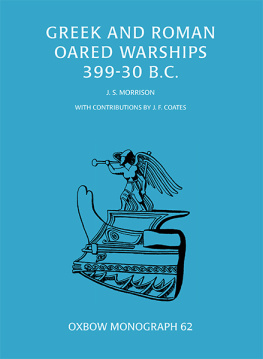

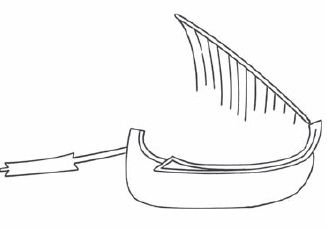

This redrawing of a Byzantine vessel is taken from a manuscript version of the Sermons of St Gregory of Nazianos, produced between 879 and 882. The original is housed in the Bibliothque nationale de France, Paris. What is most interesting here is the shape of the hull, reminiscent of the 7th-century Yassi Ada wreck, and the clear depiction of the crafts single stern rudder.