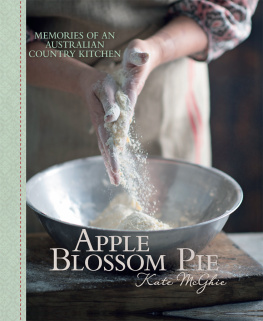

About the author

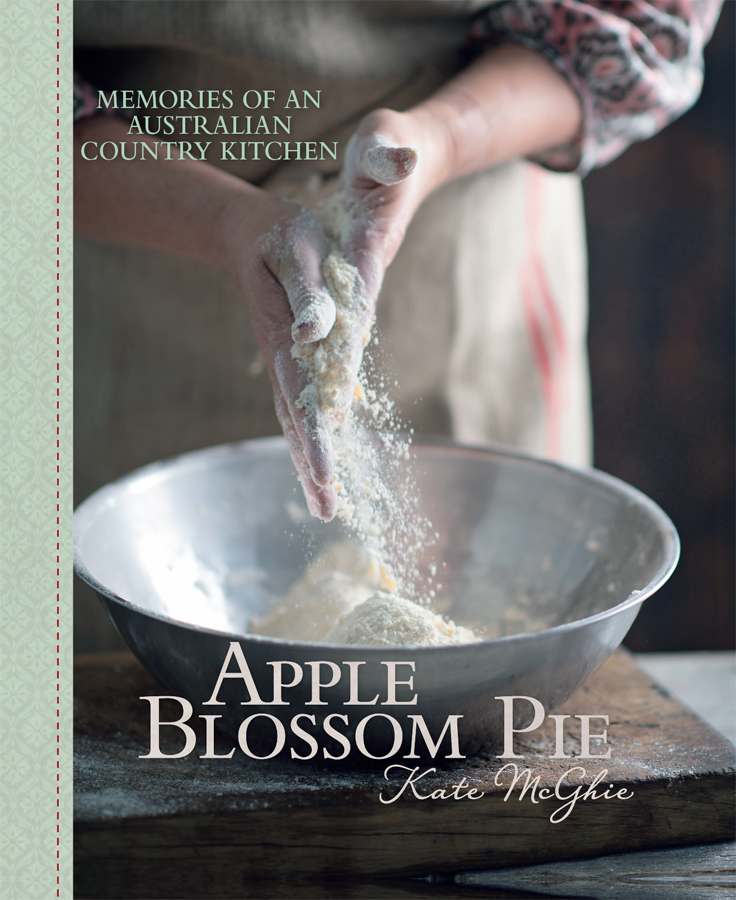

She could bake a cake long before she learned to ride a horse, snatch a chicken before she tasted pt, shin up an apple tree before shed even heard of Adam and Eve.

Kate McGhie is a qualified chef and one of Australias most respected food writers and personalities. She is the author of Cook , a much lauded title that won the coveted Australian Food Media Club award for Best Australian Cook Book (2006). Her popular Herald Sun column, published for over thirty years, now reaches some 1.5 million people every week.

Growing up on a farm in Victorias Western District, her culinary and personal inspiration has always been seasonal produce and the family and rural community of her childhood. Perched at the kitchen table, she absorbed the daily ritual and importance of food: watching her mother and grandmother cook and serve up meals (three a day, plus morning and afternoon teas) and preserve the gardens bounty with the innate wisdom and confidence of those who understand and respect the rhythms of nature.

These are memories so cherished and formative that they hover over her like guardian angelsthe rolling golden hills of grain, the shimmering summer heat, the barking of the busy blue heelers, the putter of the single cylinder engine in the dairy ...

Contents

w

w

An empty tummy is the best cook.

GRANDAD

g

Introduction

Air and Magic

My introduction to cooking was nothing more than egg whites, sugar, a whole lot of air and a little magic. I first experienced the fantasy of cooking when, as a small tot, Nana made meringues for me. Shed take an egg, break it into the palm of her cupped hand and let the white drain through her fingers into a glass. Shed hold the glass up to the light and say, Look at the sky. In my hand Im holding the sun. Then, whisking the whites, shed murmur, Now were making fluffy clouds. Holding her hand high above the bowl a fine veil of sugar would fall into the whites and the mixture would turn glossyor, as shed sayinto snow.

Small nests of meringue were dolloped onto the oven tray and, after what seemed an astonishingly long time, shed remove the crisp ivory-coloured meringues with a marshmallow heart. Life couldnt be sweeter. No richer lesson could be given to a child.

Being immersed in the relentless, marching rituals of country life, with all the joys and occasional heartbreaks, there was no such thing as not eating with the ebb and flow of the seasons. The appreciation and acceptance of imperfection and the impermanence of the food we produced and atewhere bug or bird damage or the odd bruise werent reasons to dash to the compost binwas spontaneous and a natural way of life.

But it would be false nostalgia to look back at how the old cooks in my family lived, believing it a utopia. The reality downside was that, at times, it was sheer drudgerylong hours, day in day out, with the expectation that, as well as providing three meals a day, mothers also had to be competent at other skills, such as gardening, preserving, knitting, making and washing clothes, and helping with outside chores.

We lament and grumble about commercially produced food and food preservation techniques. Possibly we are romanticising the past too much and should instead pause and ponder that some of our most taken for granted staplesrice, flour, pasta, butter, salt, coffee, chocolate, tea, sugar, vinegarare produced by industrial food companies. But to be a part of todays lifestyle we cannot seriously expect people to spend hours daily laboriously grinding wheat into flour or making chocolate.

Although I was fortunate to get an intimate, first-hand knowledge of growing and producing food, I am realistic when it comes to the difference between the yearning for a bygone, idyllic-sounding era of producing all foods ourselves, and embracing technology that produces quality ingredients. Nevertheless, I feel a little wistful that so few in future generations will experience the riches of an agrarian lifestyle.

w

I feel very lucky I was born a farmers daughter into seven generations of a family who worked the land. Our farm in Victorias Western District produced everything we atethere were Berkshire and large white pigs; dairy cattle that provided us with milk, thick cream, cheese and whey for the piggery; sheep, goats and beef cattle.

Our veggie garden was massive (it took about 100 steps in one direction and 200 in another) and the potato patch was huge, with many varieties. The orchard was shared with possums and birds.

The people who knew the farms with the best cooks and a good table were the local vicars (yes I know vicar sounds a bit strange, but that is what grandparents usually called them. Otherwise, it was the Minister or Reverend, usually reserved for Sundays) or priests. Our home was on Gods gourmet trail, which was both a compliment and at times a disadvantage. Such visitations did not always work in favour for us childreneven though we had made or assisted with many of the baked items, we were instructed to decline offerings if it were noticed the visitor scoffed more than their fair share. Which they often did. This ritual became known as FHB (family hold back).

The Michelin Restaurant rating was nothing compared with the rigour with which many a country cooks kitchen prowess was appraised by church representatives. You knew immediately your rating according to the table grace being said by the vicar or priest. If it started Behold Jehovah, well that was a Michelin star rating in todays terms. The less enthusiastic assessment would start with, May the Lord give thanks for what we are about to eat.

It was an idyllic life which immersed me in a lifelong affair with food. My food memories are just as fresh as any photographs, food blog, Instagram or Facebook page. And what photo could possibly capture the flavour of a freshly laid egg of a free-roaming country chook, perfectly poached, or the nectar of a perfectly ripe apricot plucked from the orchard?

w

These recipes draw on traditions from my past to create dishes for todays eating in a different world of cooks.

Country people eat heavier, more substantial meals because their daily lives are full of activity. My grandfather, through old age and until he took leave of this life, would, after the Sunday roast, set out on the dog runwalking the perimeter of farm paddocks, clocking up quite a few kilometres. But just reading what he ate would undoubtedly cause todays nutrition professionals to faint.

Like other country cooks, Mum was innovative in the kitchen because every day she had to put a meal on the table based on what was in the garden or in the pantry. The more limited the larder the greater the need to make use of what was there. Chefs create a menu and then find the food. Mum grew the food and created dishes to fit. The garden was pivotal to the variety of our meals. She had to be extra creative when cabbages were in abundance!

Recipes are the background scores to human orchestration, especially in rural areas. They are a diary of social events, people, places, lifestyles, ingredients, and preservation and cooking methods of the time. Among my most treasured possessions are exquisitely hand-written recipes from generations of my family. The well-worn pages, notations and grease marks bear witness to their constant use. A family recipe is also a family history.