Gingerbread

TIMELESS RECIPES FOR, CAKES, COOKIES, DESSERTS, ICE CREAM, AND CANDY

By Jennifer Lindner McGlinn

Photographs by Batrice Peltre

To my family, who so lovingly support my dreams and endeavors.

To Antonia Allegra and Don and Joan Fry who are the best friends and mentors a writer could ever hope to have.

Text copyright 2009 by Jennifer Lindner McGlinn

Photographs copyright 2009 by Batrice Peltre

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-0-8118-6191-5

eISBN: 978-1-4521-0018-0

Designed by Catherine Grishaver

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

http://www.chroniclebooks.com

I have loved gingerbread for as long as I can remember. It all started with a recipe I found in one of my grandmothers cookbooks. She had a wonderful array of recipe books, pamphlets, and magazines, some dating from the 1930s. I always had a particular fondness, though, for her 1950 edition of Betty Crockers New Picture Cook Book. I loved this binder-like collection with its old-fashioned recipes, fluorescent-colored photographs, and illustrations of pretty women wearing big skirts and high heels as they cooked. When my grandmother gave me her beloved Betty Crocker, I decided it was time tried the recipe for Favorite Gingerbread that had intrigued me for years.

The ingredients were basic and the method was easy to follow. A handheld mixer, square baking pan, some measuring cups and spoons, and a spatula were the only tools I needed to get the job done. The results exceeded my expectations. As the cake baked, it filled the kitchen with enticing, soul-satisfying aromas. Once I retrieved the mahogany-colored gingerbread from the oven, things got even better. My sisters and I cut squares of the warm cake and mounded billowy clouds of soft whipped cream on top. Moist, spicy, and sweet with molasses, the gingerbread took well to the cream, which promptly began melting into the warm crumbs. The dessert was soothing and satisfying in the way that only simple, old-fashioned dishes can be. Its no wonder that this cake has been one of my favorite comfort foods ever since.

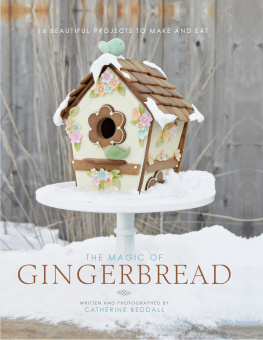

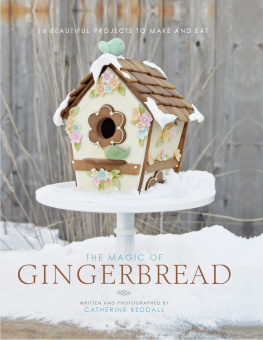

What comes to mind when you think of gingerbread? Perhaps you, too, envision gingerbread cake, dark with molasses and warm with spices. Then again, maybe crispy, crinkle-topped gingersnaps come to mind. Or perhaps you recall baking and decorating cutout gingerbread girls and boys at Christmas. And who could forget gingerbread houses? Whether decorated with gumdrops, pretzels, and candy canes, or with fancy sugar work and marzipan, these whimsical structures take homemade gingerbread to an entirely new level of artistry and skill.

Then there are the gingerbreads that hail from other parts of the world. Orange-scented, honey-sweetened cookies called Lebkuchen date back to fourteenth-century Germany. Pain dpices, from the Burgundian region of France, is a sweet spice bread flavored with honey, citrus, and aniseed. Siena, Italy, boasts panforte, a spicy fruit-and-nut confection. And fruitcake, the traditional British Christmas cake, is dense with dried fruit, fragrant with spices, and cloaked in marzipan and rolled fondant. Indeed, there are many more examples to be had, but you get the idea. Gingerbread encompasses a wide variety of sweet, spicy treats, many of which date back centuries.

The history of gingerbread is a long and colorful one, indeed. Native to Indo-Malaysia, ginger has been cultivated in subtropical Asia for more than 3,000 years. The Greeks and Romans, as well as the Chinese and Arabs, relished this spice, using it to flavor many sweet and savory dishes, including honeyed spice breads and cakes. By the Middle Ages, ginger was on the move. The Crusaders returned to Europe from the Middle East with ginger among their wide array of newfound foodstuffs and exotic spices. As ginger gained popularity in European kitchens, it continued to spread across the globe, as well. The Portuguese began growing a unique variety of ginger in Africa, and by the sixteenth century, the Spanish were cultivating what became high-quality Jamaican ginger in the West Indies.

Some of the early European gingerbreads probably resembled the Chinese spice breads from centuries earlier. Honey-sweetened, anise-scented pain dpices gained great favor in France as early as 1393. At the same time, honey-based Lebkuchen was developing a following in Nuremberg, Germany, with the first recorded Lebkuchen bakers dating to 1395. Gingerbread guilds eventually formed in Reims and Nuremberg (in 1571 and 1643, respectively), revealing the authority and places of honor these bakers held in their communities.

Other medieval gingerbreads took quite different forms. In Britain, sugar- or honey-sweetened gingerbread was usually bound with bread crumbs instead of flour. Heavily spiced and often flavored with the likes of claret wine, vinegar, rosewater, and ground almonds, the batters were either beaten into stiff pastes or cooked until thickened. They were then colored or left plain, formed into shapes or pressed into decorative wooden or ceramic molds, and left to dry.

By the late seventeenth century, this medieval-style gingerbread fell out of favor, and softer baked gingerbreads sweetened with molasses and treacle began to emerge. Rolled and shaped spice cakes (cookies, really) frequently appeared in eighteenth-century British cookery books and became popular in America, as well. Eventually, though, Americans developed a fondness for even more tender gingerbread cakes. By the late 1700s, home cooks had been using pearl ash (potassium bicarbonate) for years to lighten baked goods rich with eggs, butter, cream, and sugar. However, it wasnt until American-born Amelia Simmons published her American Cookery in 1796 that this leavener appeared in print, along with no less than five of her gingerbread recipes. Many writers eventually followed Simmonss lead. As authors such as Eliza Leslie, Lydia Maria Child, and Fannie Merritt Farmer wrote about American cooking and baking, they continued to compile recipes for all sorts of gingerbread cakes and cookies. Happily, the trend has continued.

If spicy, molasses-rich cake enticed me to fall for gingerbread as a child, many other gingery treats have further seduced me as an adult. From cakes and cookies to desserts and breakfast treats to confections and ice creams to fanciful spiced structures, gingerbread takes many delicious forms. Although all the recipes in this book call for ginger in some form (powdered, crystallized, or fresh), you will find that the ancillary ingredients are flavorfully varied. Molasses, brown sugar, and spices, such as cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and allspice, appear frequently, but not always. You will find gingerbreads sweetened with honey and golden syrup; spiced with aniseed, cardamom, coriander, Chinese five-spice powder, and mustard powder; flavored with citrus, chocolate, and rum; and textured with oat bran and almond and rice flours. Some are moist, soft, and as dark as ebony, while others are crisp, firm, and golden blond.

Most of us have come to think of gingerbread as an exclusively fall and winter dessert, and understandably so. Who wouldnt want to cuddle up by the fire with a batch of soft molasses cookies or a warm square of fragrant gingerbread cake? With its many enticing varieties, however, gingerbread certainly deserves to be celebrated year-round. Whether you like your gingerbread vibrant with spices or delicately perfumed, warm right out of the oven or firm and chilled from the freezer, there are plenty of ways to enjoy it no matter the season.