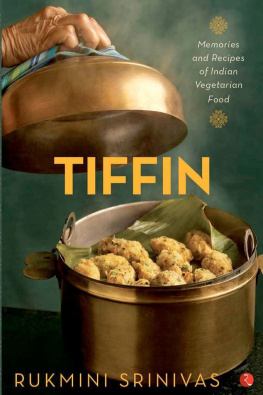

TIFFIN

~ for Lakshmi and Tulasi ~

First published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2015

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Copyright Rukmini Srinivas 2015

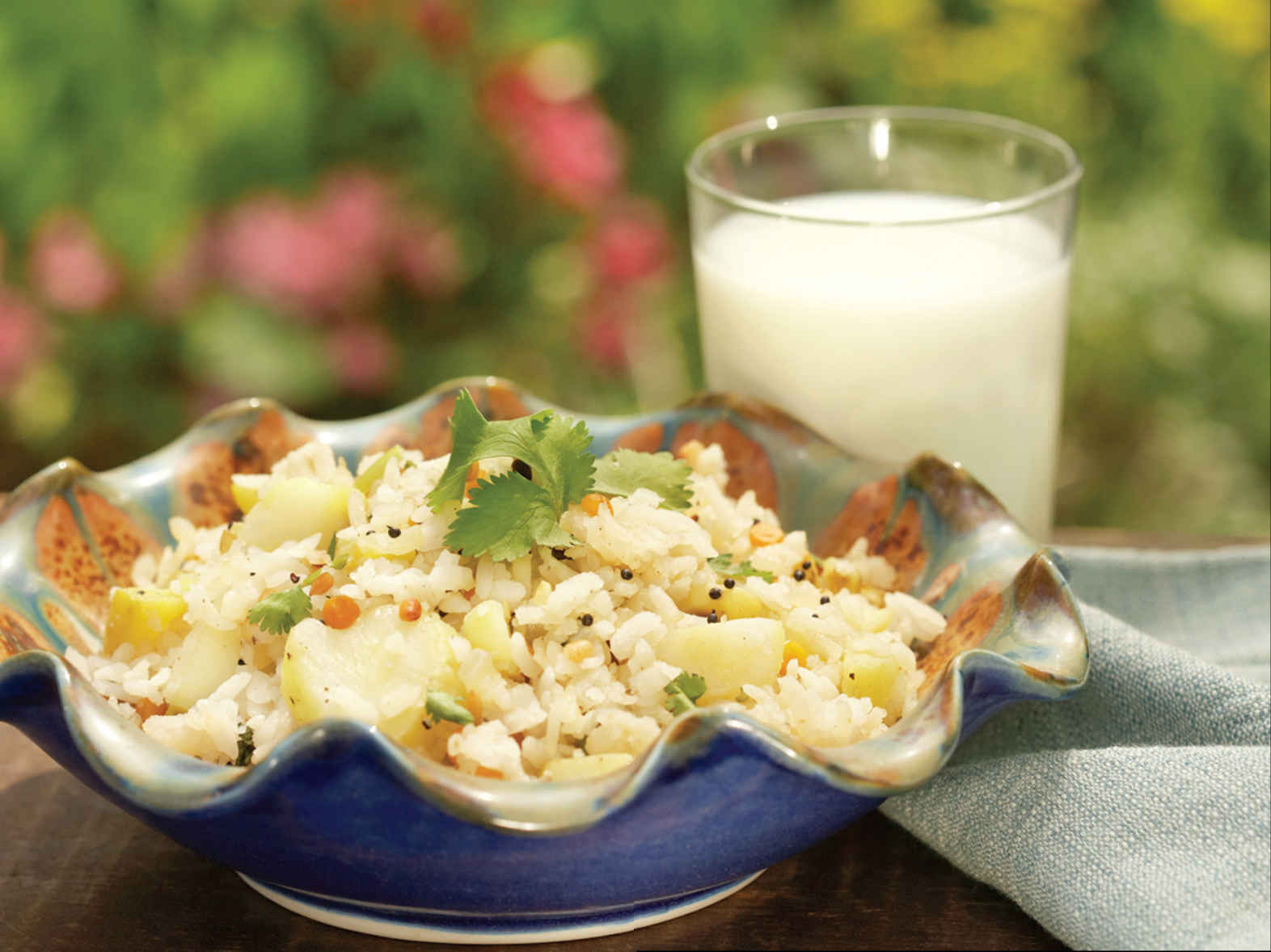

Food photographs by Nina Gallant in Boston and Mahesh Bhat in Bengaluru

Family photographs from the authors album

Book design by Maithili Doshi Aphale

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-81-291-2390-9

First impression 2015

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Typeset by Rajkumari John

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Captain Thomas Williamson, in his The East India Vade-Mecum, describes tiffin as a little avant dinner taken at 1.00 or 2.00 p.m., a time which remained unchanged right up until Indias independence from British rule. The word tiffin itself is thought to be derived from tiffing, an eighteenth-century English slang term for sipping.

Tiffinluncheon, Anglo-Indian and Hindustani, at least in Englishwe believe the word to be a local survival of an English colloquial or slang term. Thus, we find in the Lexicon Balatronicum, compiled originally by Captain Francis Grose (1785): Tiffing, eating or drinking out of mealtime, besides other meanings.

In the delightful European in India or Anglo-Indians Vade-Mecum by E.C.P. Hull, with a Medical Guide for Anglo-Indians by R.S. Mair, published in 1878, I came across this helpful entry for tiffin: Tiffin, if not made the principal meal of the day, should invariably be light, and consist only of bread or biscuit, fruits and a glass of sherry or claret. Hull goes on to say, Some people make tiffin an excuse for a double dinner, but anyone who eats largely at both these meals, eats more than is necessary. Heavy tiffins make men heavy, sleepy and interfere with due performance of active work in the after-part of the day. Either take a substantial tiffin and a light dinner, or a substantial dinner and a light tiffin.

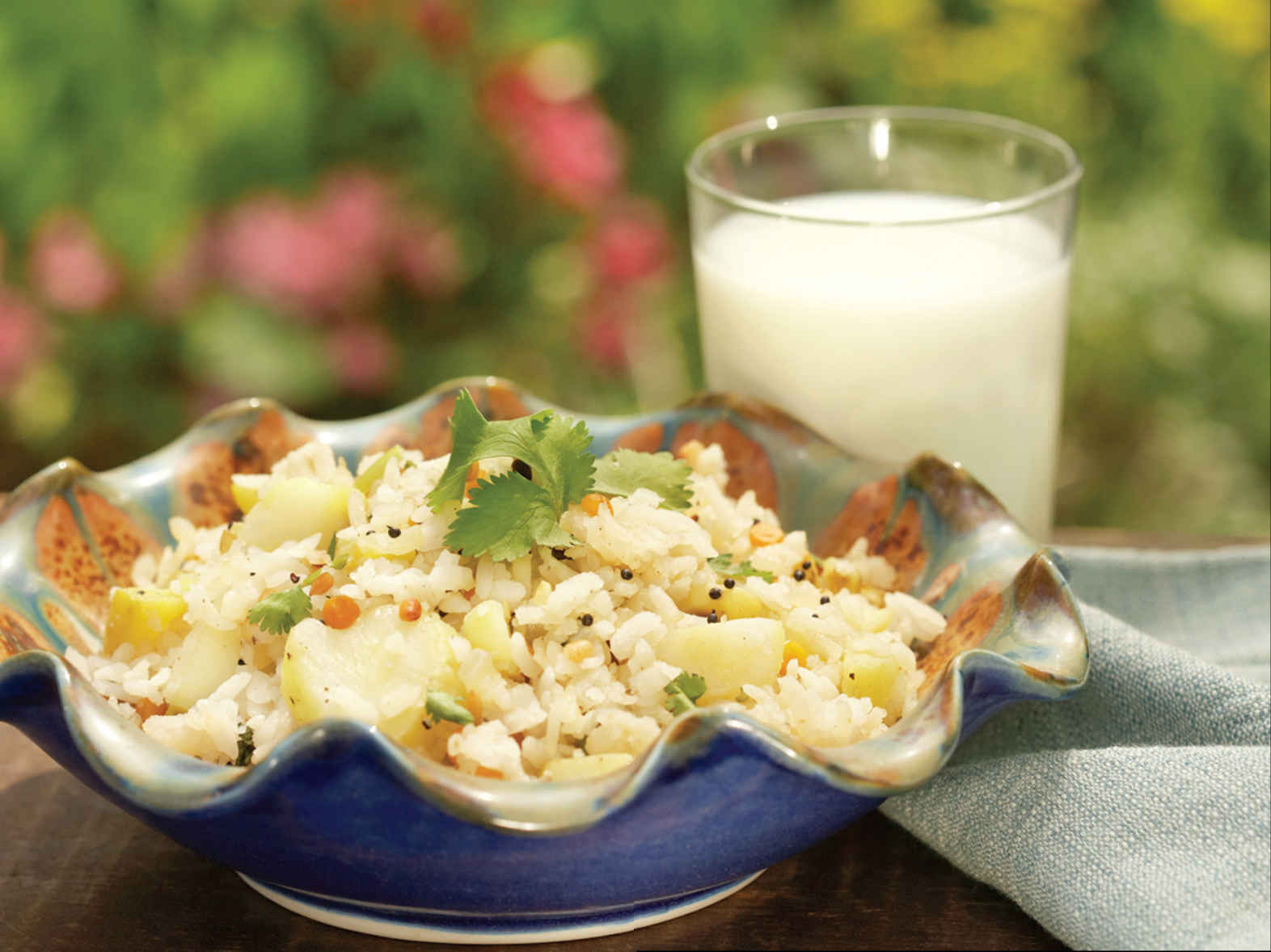

K.T. Achaya in A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food, 1998, writes: Tiffin was a light midday meal enjoyed by 19th century British families stationed in India In colonial India, when the evening dinner became a heavy daily repast, only a light afternoon meal was necessary. This was called Tiffin, a word which first appears in ad 1807 in Anglo-Indian writing. The word tiffin itself is a colloquial English term, which comes from the word tiffing for eating and drinking out of mealtimes, and the word tiff which was to eat the midday meal. The word Tiffin has been adopted particularly in the Madras area for a light afternoon snack of items like the uppama, dosai and vada to the extent that many take it to be an Indian language word.

Going by these references, tiffin is a play on the time of day and the nature of food served in many homes in Indiaan informal snack or light meal served at breakfast or with late afternoon tea. Significantly, as dinner time changed and was pushed to later in the evening, there was a change in the nature of the food in India, and tiffin, the transition food, became important and continues to be so. Several small commercial eateries known as tiffin rooms became populartwo such in Bangalore (now Bengaluru) that I know of and frequent are the Mavalli Tiffin Room, or MTR, and the Central Tiffin Room. MTR, located on Lalbagh Road in South Bangalore, in the very busy commercial locality adjoining the famous Lalbagh Botanical Garden, is a pilgrimage centre for foodies from all over India and abroad, and has earned its rightful place in the global world of food consumption with its export of packaged spices and ready-to-eat convenience foods.

On the other hand, the Central Tiffin Room in Malleswaram, a suburb in north Bangalore, is low profile and a favourite haunt of the local denizens. Serving only tiffin, just as your mother made it, this small eatery at the junction of two roads is always crowded. But the service is efficient and cordial, and the few minutes wait is amply rewarded by fresh off-the-fire tiffin items, accompanied by rich, fragrant, south Indian style filter coffee with milk and sugar.

Eateries such as these, with their own eclectic fare, dot the cityscape in India. Recently, while travelling by road in south India with my friends Krishna and Aruna Chidambi, we ate at several small and big eateries. Some were several storeys high, while others were very modest, thatched huts displaying signboards in Tamil that said Tippen Taiyaar, meaning, Tiffin and Meals Ready.

With Krishna and Aruna Chidambi

In an age when office canteens, eating out joints, take-aways and tuck shops were not as common as they are now, tiffin tended to be made more at home than outside. My mother, whom I lovingly call Amma, spent much time and thought in the preparation of the everyday tiffin for me and my seven sisters. When I was in school between 1932 and 1946, I would leave home by 8.00 a.m., which was too early for me to have a proper breakfast. I could barely down the banana milkshake Appa (my father) made for me. Frequently, the sandwich packed by Amma for the eleven oclock break would be untouched till lunchtime. Playing or chatting with friends left no time for the snack. Opening my lunchbox, she would be distressed to find that I had eaten only a portion of what she had packed. Little wonder that I was ravenously hungry on my return from school around 4.30 in the evening. The tiffin that Amma made, usually one savoury and one sweet, would be a full meal for me. And, every day, it was a delicious surprise.

Next to a restaurant board in Tamil Nadu

My sisters and I had our own lunch dabba, a rectangular metal box 10 inches 5 inches 2 inches, which would be washed and reused every day. More elaborate meals would be packed into a stack of such containers made of brass or stainless steela tiffin carrierwhich was used by the family on picnics or train journeys.

Next page