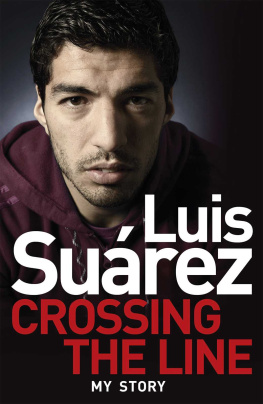

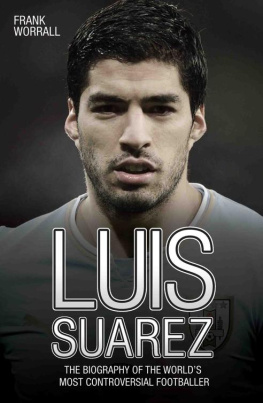

Copyright 2014 Luis Surez

The right of Luis Surez to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2014

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781 4 7222 425 5

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.headline.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

CONTENTS

About the book

Luis Surez was a young boy already in love with football by the time his family moved from the countryside to Uruguays capital, Montevideo. The guile and trickery of the street kid made an impact with the countrys biggest club, Nacional, before he was spotted by Dutch scouts who brought him to Europe.

Surez was lured from Ajax to Merseyside by another iconic number 7, Kenny Dalglish. From that moment, he terrorised Premier League defences, driving a resurgent Liverpool towards their most exciting top-flight season in 24 years.

But there is another side to Luis Surez: the naturally fiery temperament which drives his competitiveness on the pitch. There was the very public incident with Patrice Evra of bitter rivals Manchester United, and the biting of Chelsea defender Branislav Ivanovic, for which Surez received eight- and ten-match suspensions respectively.

Then during the World Cup finals in Brazil, in a physical encounter against Italy, he bit defender Giorgi Chiellini on the shoulder. Banned from football for four months, derided by the press, he left Brazil in the most testing of circumstances.

In the summers final twist, he became one of the most expensive footballers of all time, moving from Liverpool to Barcelona.

In Crossing the Line, Luis Surez talks from the heart about his intriguing career, his personal journey from scrapping street kid to performer on footballs biggest stage, and the never-say-die attitude that sometimes causes him to overstep the mark.

About the Author

Luis Alberto Surez Diaz was born in the Uruguayan city of Salto on January 24 1987. When he was seven his family moved to Montevideo and fell in love with football. Rapidly rising to a first-team position for locals Club Nacional de Football, it wasnt long before he was plying his trade in Holland first with Groningen and then superstars Ajax, where he was named Dutch Footballer of the Year and amassed one hundred goals for the club.

In January 2011 Liverpool manager Kenny Dalglish paid 22.8m pounds to secure Suarezs services, making him the most expensive player for the club at the time. Suarez scored on his debut in front of the Kop, and wrote himself into Merseyside folklore. On 30 March 2014, he broke Robbie Fowlers club record of 28 goals in a Premier League season, and won the Golden Boot, before moving to Spanish superstars Barcelona. At international level, he is Uruguays alltime record goalscorer.

For Sofi, Delfi and Benja. I love you.

INTRODUCTION: CROSSING THE LINE

I knew straight away, as soon as it happened.

When Godn scored I said Gol! but on the inside everything was shutting down. I was happy that we had scored, and happy for my team-mates that we were going through, but I didnt want to think any more thinking meant accepting what Id done and what the consequences would now be.

I had let people down. My coach scar Tabrez, El Maestro, was in a bad way in the dressing room because he knew what could happen to me now. I couldnt look at my team-mates. I couldnt look at the Maestro. I didnt know how I could say sorry to them. He told me that after the game the journalists had asked him about the incident, and hed told them that he hadnt seen anything.

My team-mates were trying to tell me that maybe the situation was not so bad. But I didnt want to hear a single word of it. Two more days would pass before I had to leave Brazil, but in my head, I was already gone.

I was at training the next day, still in this unconscious state of denial, not wanting to think about anything, much less face up to the need to apologise and accept the fact that I needed to get some help.

Just as we finished the training session, the Maestro called me over. He had news. This is the worst thing that I have ever had to tell a player, he said, hardly able to get the words out. At that moment I thought maybe the ban would be ten, fifteen or even twenty games, but then he said: Nine matches. That didnt seem any worse than I had feared. But he wasnt finished. And you cant set foot in any stadium. You have to leave now. You cant be anywhere near the squad.

I wanted to stay and support my team-mates. Even if I was not playing I wanted to try to make up for things in some small way. But there were representatives from FIFA at the hotel and the team manager, Eduardo Belza, had been informed that I had to leave the squad as soon as possible. They treated me worse than a criminal. You can punish a player, you can ban a player from playing, but can you prohibit him from being alongside his team-mates?

The nine-game ban was to be expected. But being sent home and banned from all stadiums? The only reason I didnt cry was that I was standing there in front of the coach when he told me the news.

There was a meeting with the team afterwards back at the hotel. I wanted to speak to them during lunch, but I couldnt. I was about to stand up and tell them to be strong, to keep going, to keep fighting, but I just couldnt.

Had the ban stopped at nine Uruguay matches which, as would gradually dawn on me, is a heartbreaking two tournaments and two years out of international football I might still have challenged it, but I would have understood it. But banning me from playing for Liverpool when my bans in England never prevented me from playing for Uruguay? Banning me from going to watch my nine- and ten-year-old nephews play a game of Baby Football? Banning me from all stadiums worldwide? Telling me that I couldnt go to work? Stopping me from even jogging around the perimeter of a football pitch? It still seems incredible to me that, until the Court of Arbitration decreed otherwise, FIFAs power actually went that far.

They had never banned a player like that before for breaking someones leg, or smashing someones nose across his face as Mauro Tassotti did to Luis Enrique at the 1994 World Cup. They made a big thing of saying the incident had happened before the eyes of the world. Zinedine Zidane headbutted Marco Materazzi in a World Cup final in 2006 and got a three-match ban.

I was an easy target, maybe. But there was something important I had to face up to: I had made myself an easy target. I made the mistake. It was my fault. This was the third time it had happened. I needed to work at this with the right people. I needed help.

After my ten-match ban in 2013 for biting Branislav Ivanovi, I had questioned the double standards and how the fact that no one actually gets hurt is never taken into consideration. The damage to the player is incomparable with that suffered by a horrendous challenge. Sometimes English football takes pride in having the lowest yellow-card count in Europe, but of course it will have if you can take someones leg off and still not be booked. When they can say it is the league with the fewest career-threatening tackles then it will be something to be proud of.

Next page