This book is for all cooks.

Its ok to lose your way: sometimes its needed.

For my beautiful family: Polly, Harriet and Henry.

You make me a better cook.

Contents

Foreword

Peter Gilmore, Executive Chef, Quay and Bennelong restaurants, Sydney

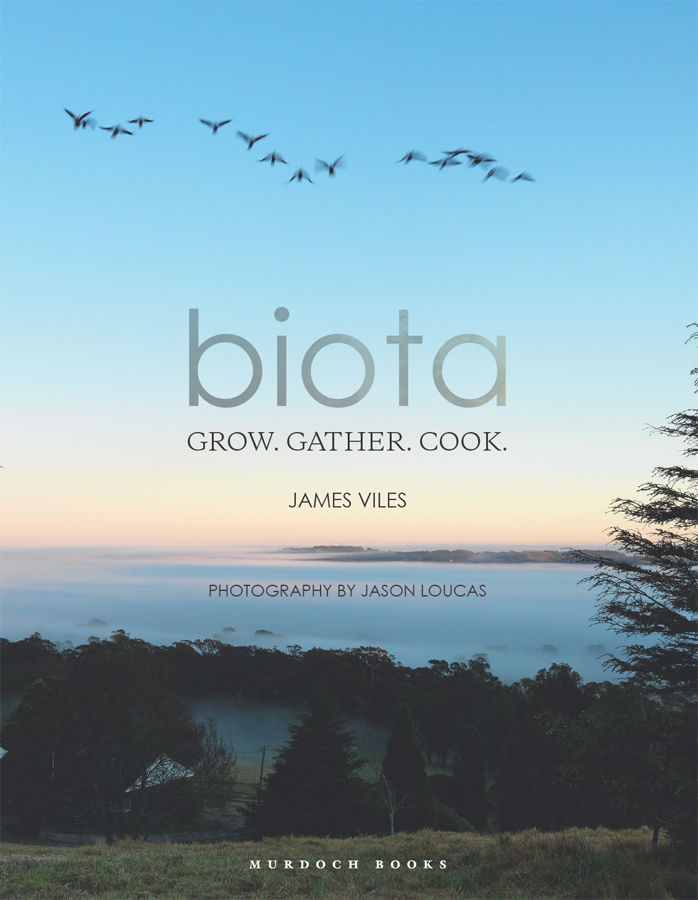

In many ways James Viles is a man after my own heart. His interest in the sheer diversity that nature offers the chef and his passion for growing his own produce have shaped and informed the way James approaches his cuisine at Biota Dining.

James cooks in a very modern way and over the last four years he has developed a personal style that truly embraces and reflects his local environment. James has built genuine relationships with local farmers and producers and these have become an integral part of his cuisine; the evidence of this bears fruit on his menus.

This book represents James passion for his region and documents his commitment to hunt and gather, grow and cultivate from his environment to create a truly regional cuisine.

A journey

James Viles

What is biota? Not just the restaurant biota is the plant and animal life of a region, our region. To me, biota is a notion, a philosophy that guides us towards mother nature and helps us create from our local farms, forests and gardens. We find ourselves making the most of every ingredient. To some this would be called a sustainable approach; to us its just a way of life.

But it didnt start like that for me. At the age of 24 I was fresh into a restaurant in Bowral in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, a small town 690 metres above sea level with a yet-to-be-discovered diverse microclimate. I thought I had found the food that I wanted to cook, food that was pretty damned special when, in fact, what I was cooking was food with no home and no heart. I was working among a bounty of streams, wild meat, weeds and lush roadside fruit, in a region that was untouched, raw and ready and I didnt even know it. I dont remember visiting, talking to and learning from the surrounding farms. I bought meat from a local butcher, but I didnt ask where it was from. I certainly dont remember asking what breed it was and what it was fed or for how long. I didnt know that the oxalis growing in the cobbled steps outside the kitchen door was one of the most beautiful weeds I could find; I didnt even notice its tiny yellow flowers come to life for six weeks of the year. So what happened?

I went away, like many chefs. But I didnt go to Europe and work in the best Michelin kitchens; I went to the Middle East, to Dubai. I was an eager young guy from the country and ready to see and experience everything I could, and I did just that. I took a position as chef de cuisine of a 500-room hotel that had over 200 chefs. I had never seen so many different nationalities, so many different restaurants and cuisines in one place. The hotel was like its own little city. I suddenly found myself running one of the top western-style restaurants in the Middle East. It was two levels of pure excess 30 chefs for 60 seats, the same in floor staff and me with my own office. Now why the hell does a 25-year-old chef who should be cooking need an office? I found that out very quickly I would sit, 50 floors high in the Arabian sky, ordering duck foie gras from France and goose foie gras from Morocco, branded caviar from Russia, seafood from New Zealand, beef from Argentina, Australia and the USA, fruit from Syria, lamb from Pakistan and vegetables from France all to the sound of the lunch service. For two years I learned the politics of running a hotel kitchen; I cooked tastings for already well-fed hotel executives; I made sure my uniform was pristine and that I looked the part. I was young and it was all new.

I found myself driving and looking at the side of the road more than the road itself, hoping to see the young shoots of wild fennel or red stem dandelion. The more I looked the more I found.

Then I took on a role as executive chef of a five-star hotel in Oman. When I got there, a cyclone had just ripped through the city of Muscat and the hotel had to be closed down for five months for rebuilding. I have never felt so far out of my depth. I had 110 chefs waiting to come back to work and five restaurants to rebuild and refit. I had bitten off way more than I could chew, but I chewed like buggery and we opened. And the same thing happened: I wore a chefs uniform and looked like a chef, but I didnt cook; I didnt even touch the food I was ordering; sometimes I didnt even know if it had come in. Two years later, I was extremely well versed in supply chain logistics, menu engineering and the running of a large multi-national kitchen, but I had an itch.

So, I had experienced a small local restaurant with five staff, and a kitchen in the Middle East that made Las Vegas feel organic. I had a choice to make. I missed the country, I missed the smells, I missed Australia and I missed the freedom to be myself. I was more mature and I had purpose, something that I had never had before. I walked around this property in Bowral with my father, and he kept saying, Do you think we could make this something special? My senses were alive: there were blackberries, dandelions, ducks, water, honeysuckle, snakes, sorrel and clovers; the air was clean, the grounds were lush, although somewhat wild, my heart was alive and I was excited. I found myself asking questions: what is this, is it edible, how can I use it? I was hungry for answers. I met local growers and farmers and they inspired me; I went into the woods and there were deer to watch and mushrooms to pick from the forest floor; I gathered lavender, wood sorrel, fiddle fern and oily pine needles. I found myself driving and looking at the side of the road more than the road itself, hoping to see the young shoots of wild fennel or red-stem dandelion. The more I looked the more I found.

Finally, it was making sense; the ingredients and the food had found me when I wasnt looking. I was just aware of my surrounds and all I had to do was join the dots and do things with integrity. I started asking, what is produce to a chef? Is produce the same as ingredients? What is the difference between a cook and a chef? I can only say what I think, but the reality of produce versus ingredients is simple to me: produce belongs to the producers, the farmers and growers who invest blood, sweat and tears in what they believe; ultimately that belongs to mother nature. Ingredients, on the other hand, belong to us, the cooks. We cook the ingredients that belong to the environment, the producers and the growers. As cooks we have a responsibility to treat the ingredients with good intent, and try to tell beautiful stories of the habitat, connection and the producers.

This might sound very simple, but we are all at the mercy of mother nature in everything we do; she is one variable that cannot be tamed. So why waste any of our time trying to change her? Why waste energy trying to make tomatoes grow for two months longer? Or try to pick saffron milk caps in the forest in summer? We need to teach ourselves to be patient, be happy with whats on offer and use it to our best abilities.