One

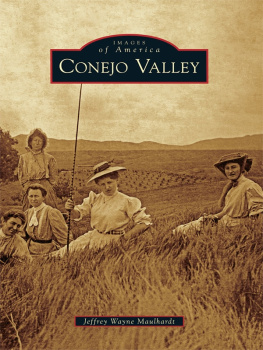

THE LAND OF THE CALIFORNIOS

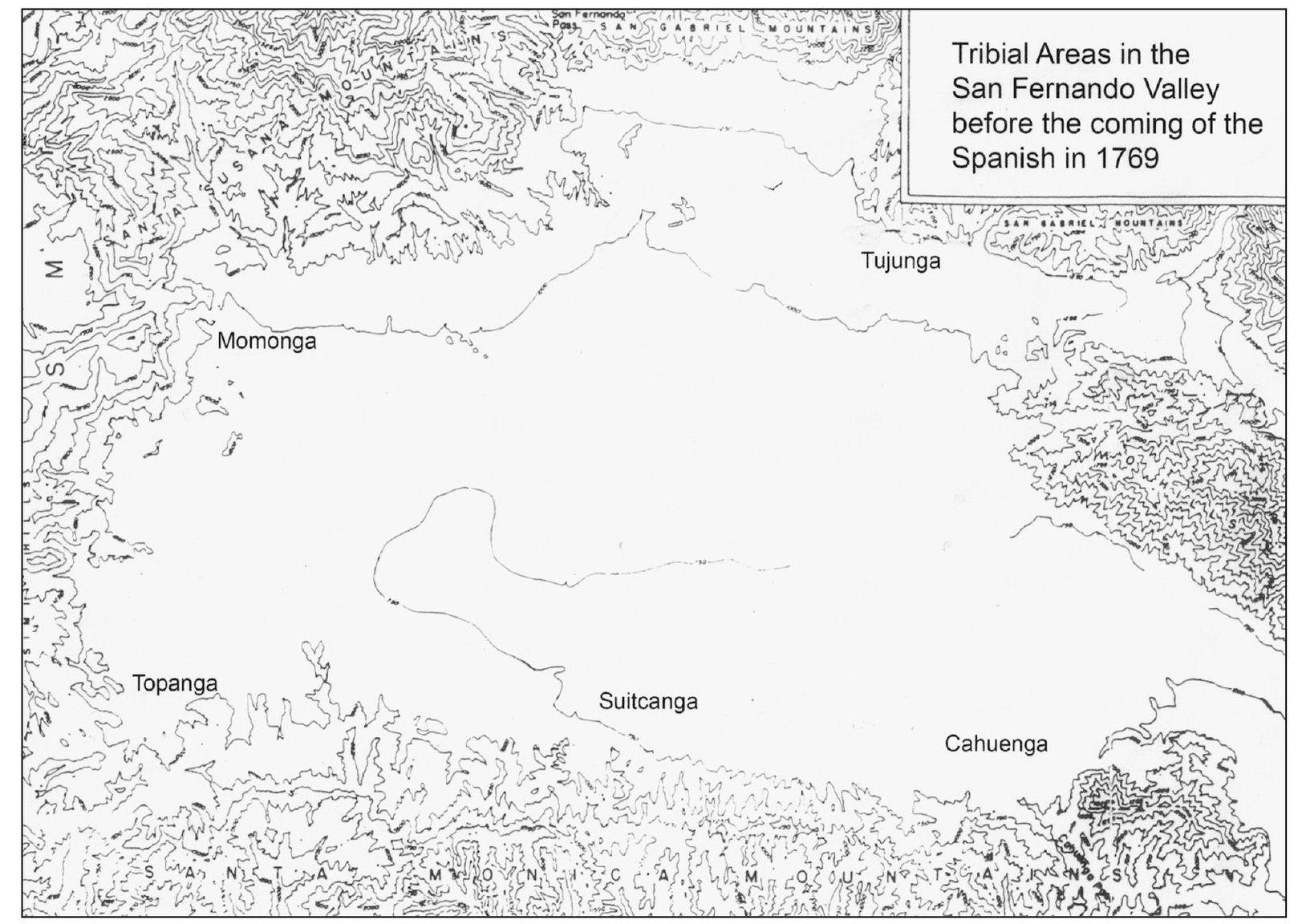

This tribal map shows Shoshone and Chumash ranchorias , or villages, that populated the semiarid San Fernando Valley before the Spanish arrived in 1769. The native people utilized the freshwater springs and streams along with other abundant resources of the fertile San Fernando Valley. They had been living there for the past 4,000 years. The Tataviam, Chumash, and Tongva Indian tribes lived together along the hillside of the valley. Suitcanga (Encino), Kawengna (Cahuenga), Topanga, Momonga (Chatsworth), and Tujunga were the various village names found on the San Fernando Mission registers. The Chumash territory spread from present-day Malibu and Topanga to southern Monterey County. The Tataviam people settled in the Santa Clarita Valley. Tataviam roughly translates to People of the southern slopes. The Tongva people occupied the area around Los Angeles and the San Gabriel Valley. The native Tongva used the nga sound to denote place names.

Gaspar de Portola led an expedition over the Sepulveda Pass on August 5, 1769. Father Crespi wrote, We saw a very pleasant and spacious valley. We descended to it and stopped close to a watering place, which is a large pool. Near it we found a village of heathen, very friendly and docile. We gave to this plain the name of Santa Catalina de Bononia de Los Encinos.

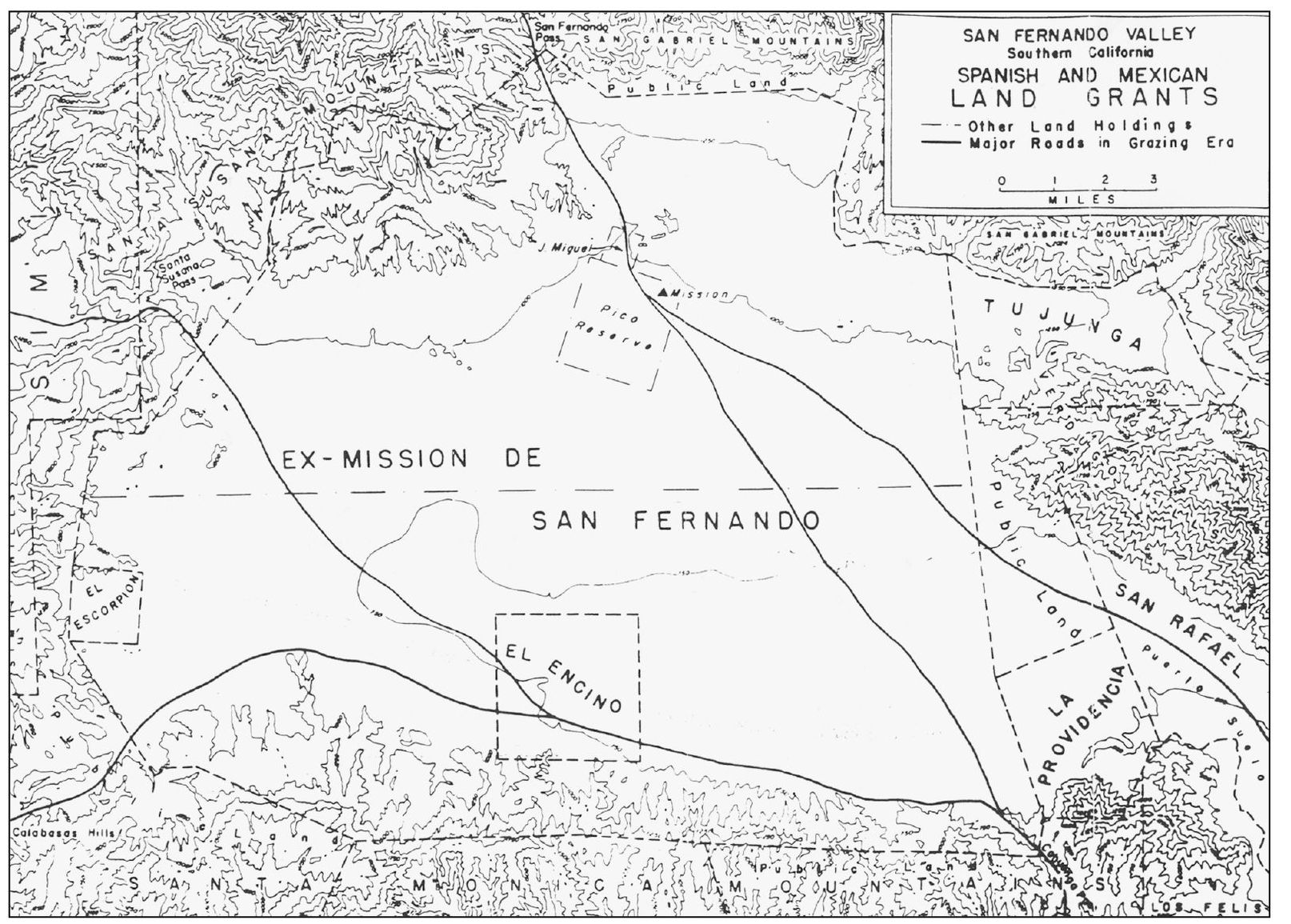

Mission San Fernando Rey de Espaa was founded in 1797 on the site of the Pashecgna village but closed following Mexicos Secularization Laws of 1834. At its peak, the mission had 30,000 grapevines, winemaking facilities, and 21,000 head of cattle. The valley holdings were divided up into the five land grants of El Escorpion, El Encino, El Providencia, the Pico Reserve, and the exMission San Fernando.

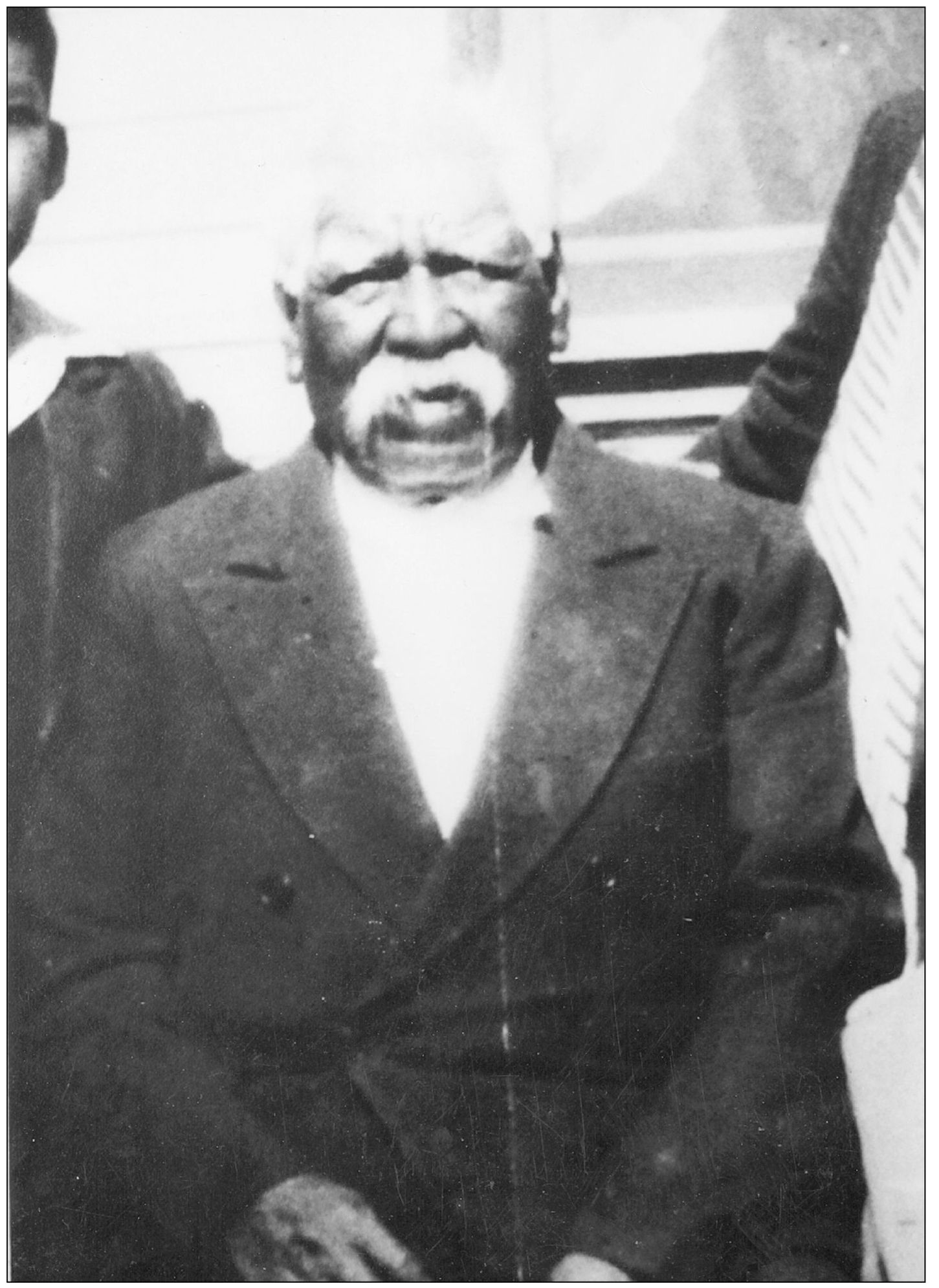

Antonio Ortegas great-grandfather Tiburcio Cayo, originally from the Taapu Village in the Santa Clarita Valley, spent most of his life in service at the San Fernando Mission. When the mission system dissolved, he homesteaded the land around the Encino spring in 1838. In 1840, a license was granted to Tiburcio. After Tiburcios death, Mexican governor Pio Pico formally granted El Encino to Roman, Francisco, and Roque on July 18, 1845. But as family members began to die, the ranch could not be maintained, and taxes fell behind; they were forced to sell the ranch. Tiburcios wife, Teresa, and their two daughters, Paula and Aquida, continued to live on the rancho. Rita, the daughter of Paula and Francisco, gave birth to Antonio Ortega on the rancho in 1849. (Courtesy of Beverly Folkes.)

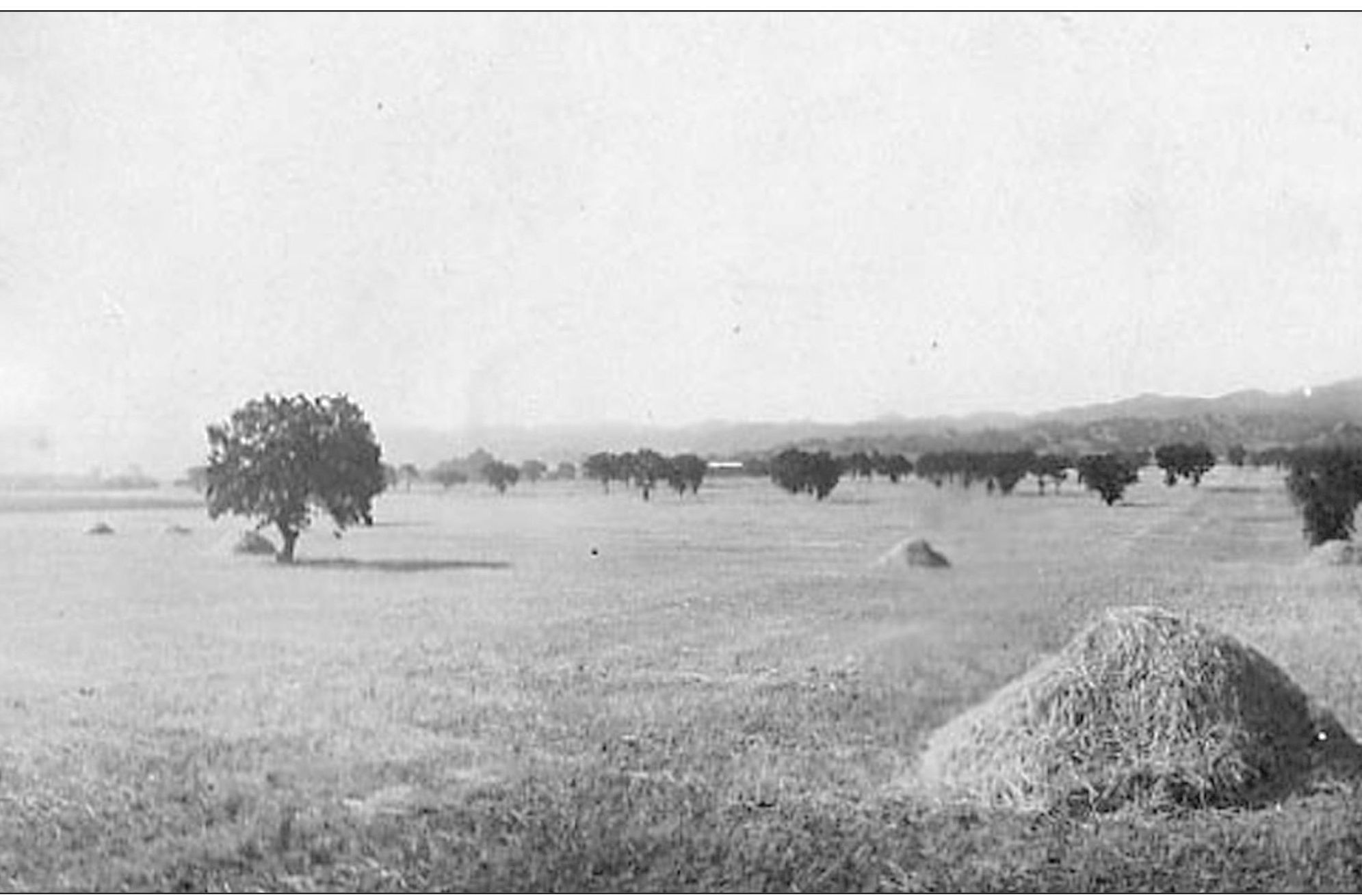

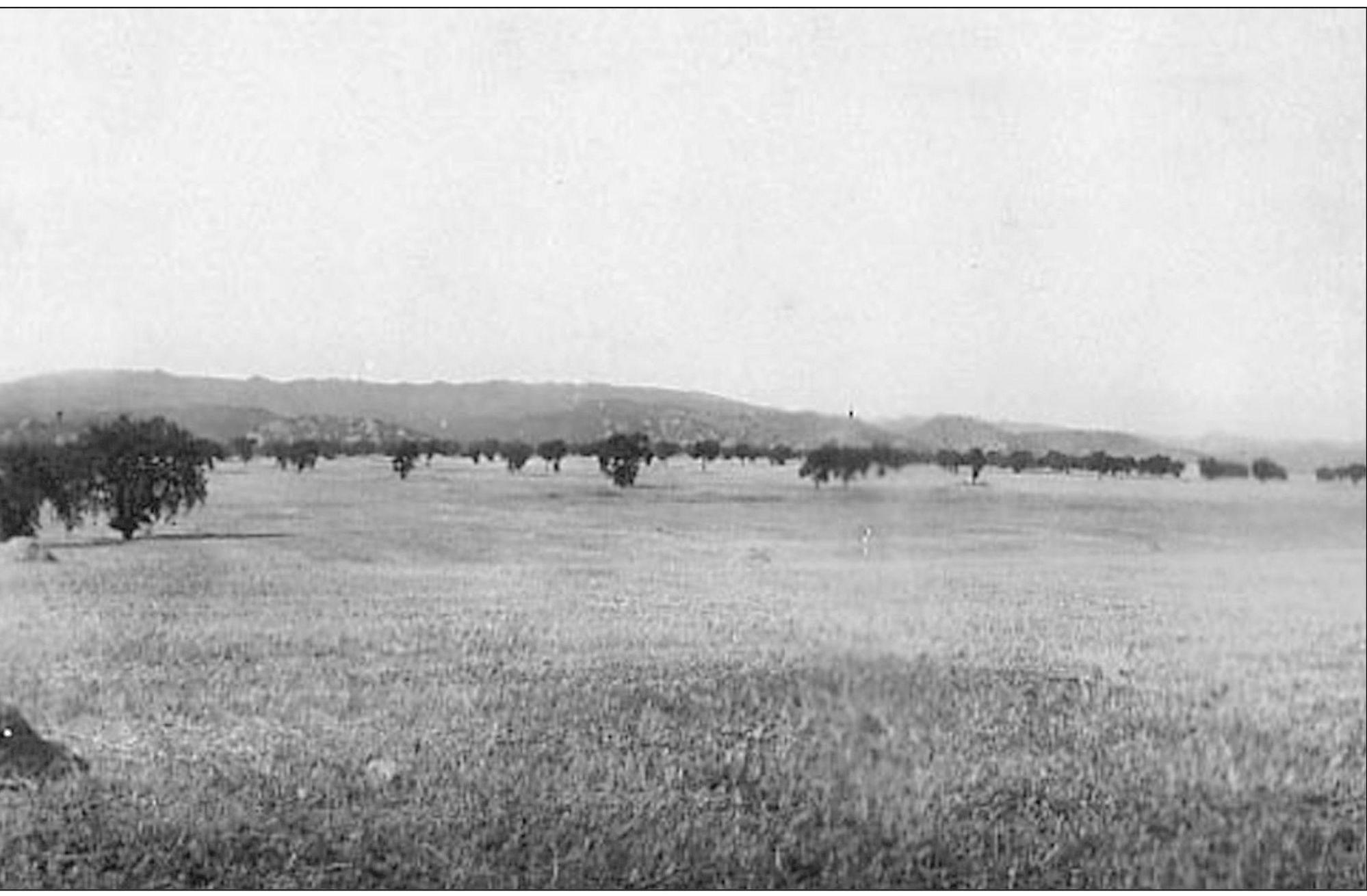

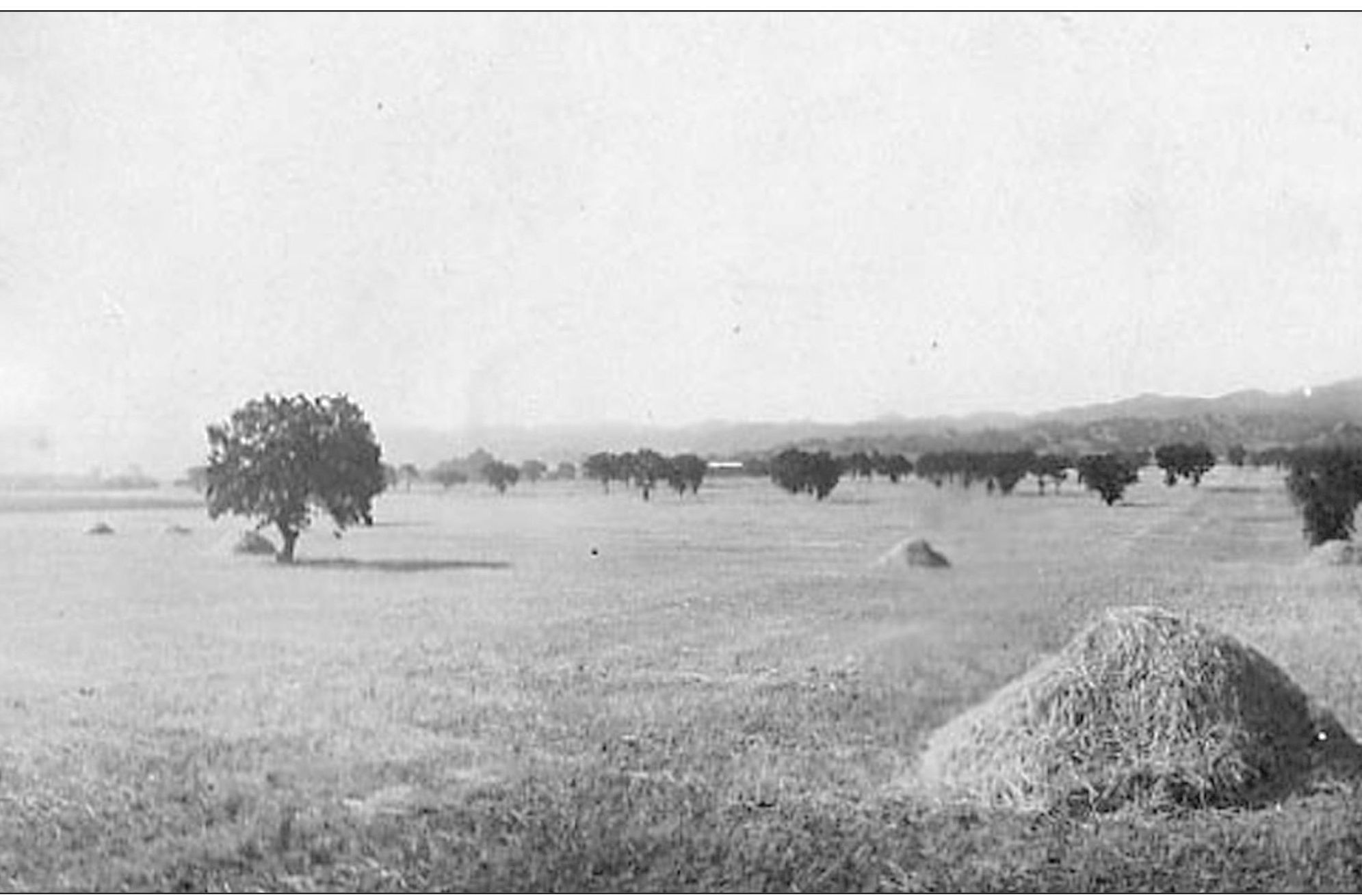

This panoramic view of the Encino hay field in 1915 offers a glimpse of what the valley might have looked like before it became urbanized. In order to see what Encino looked like 100 years ago, one has to remove all the houses and streets, all the office buildings and shopping malls, and leave only scattered groves of oak trees and an empty plain. The mission brought cattle and horse ranching into the valley, followed by the sheep industry of the 1870s. When the wool market fell, dry crops such as wheat and barley were grown. Eventually, as smaller farms sprang up with the import of Owens Valley water in 1913, other crops included alfalfa, apricots, asparagus, barley hay, beans, beets, cabbage, citrus, corn, lettuce, melons, peaches, potatoes, pumpkins, squash, tomatoes, and walnuts. But valley agriculture slowly died after the end of World War II.

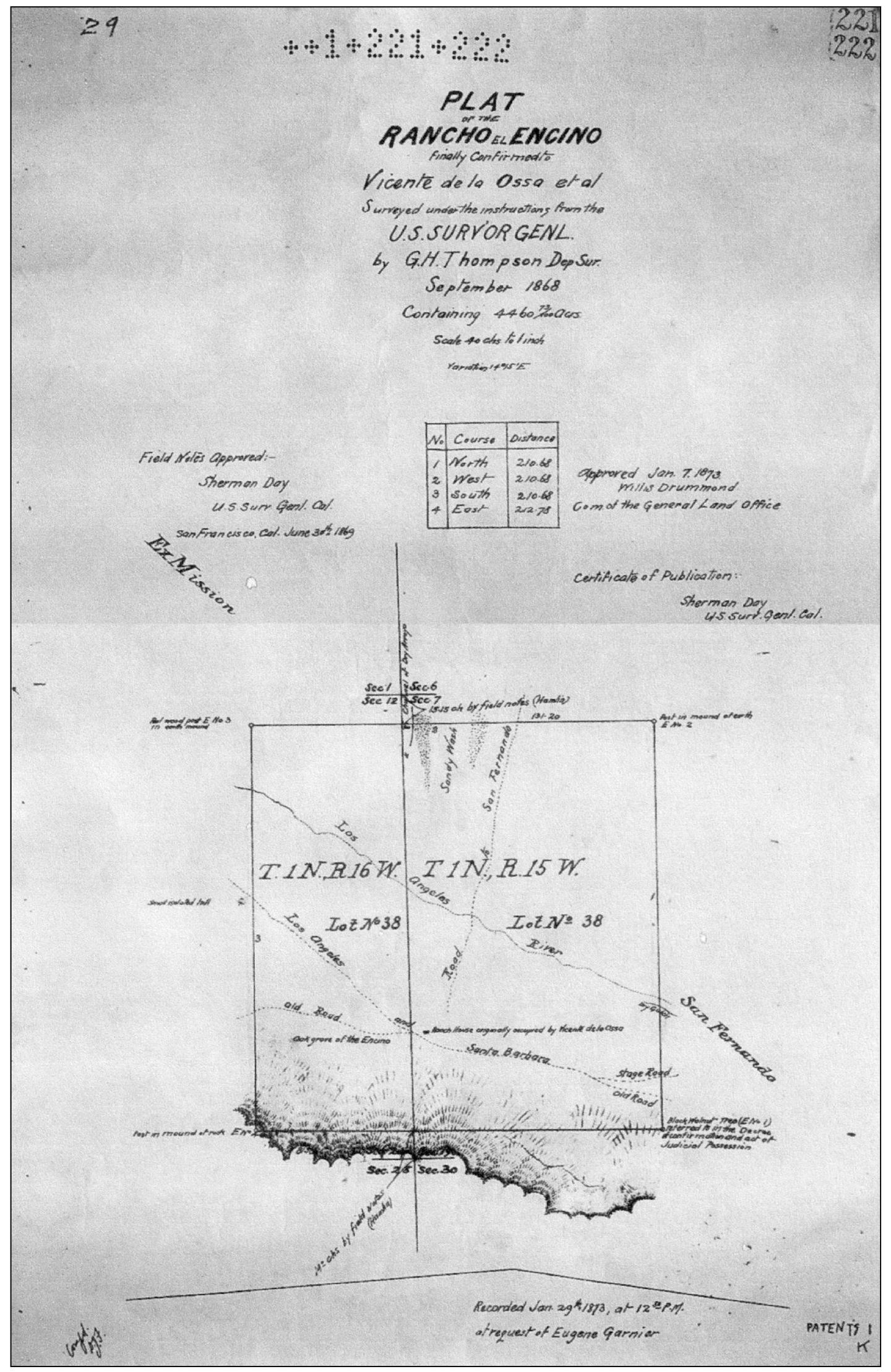

This official plat map drawn up for Frenchman Eugene Garnier shows that the original boundary of the Encino Rancho land grant included 4,460 acres. Todays boundaries correspond with what is now White Oak Boulevard from Haynes Street, south to the Encino Reservoir, east to Firmament Avenue near Sutton Street, north to Haynes Street, and then back to White Oak.